Cruikshank (Gorton, Strathspey)

For family tree see Alexander Cruikshank on Ancestry (subscription required)

The Cruikshank family farmed in Strathspey for generations before, in the mid-1700s, at least four brothers – James (1748–1830), Patrick (1749–97), Alexander (1772–1846) and John (1766–1810) – went to St Vincent, which had been ceded to Britain in 1763. They arrived either as ‘poor settlers’ or as tradesmen. Their father Duncan Cruikshank was tacksman [tenant] of Gorton, an area of farmland and birch woods on the rolling hills just north of Grantown on Spey, and other relations also had tenancies in the area.

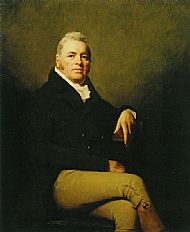

The oldest brother, James, returned from St Vincent and bought land near Montrose which he renamed Langley Park after the plantation in St Vincent which he now owned. The second son Patrick returned to Edinburgh where he married in 1776 and, at the birth of his daughter in 1779, was described as ‘late of the island of St Vincent, carpenter’. Although a tradesman, by 1791 he was the owner of the estate of Stracathro, north-east of Brechin. These two brothers married two of the daughters of Gilbert Gerrard, professor of philosophy at Aberdeen, in 1791 and 1793; and James and his wife Marjory had their portraits painted by Henry Raeburn, paintings which now hang in the Frick Gallery in New York.

The oldest brother, James, returned from St Vincent and bought land near Montrose which he renamed Langley Park after the plantation in St Vincent which he now owned. The second son Patrick returned to Edinburgh where he married in 1776 and, at the birth of his daughter in 1779, was described as ‘late of the island of St Vincent, carpenter’. Although a tradesman, by 1791 he was the owner of the estate of Stracathro, north-east of Brechin. These two brothers married two of the daughters of Gilbert Gerrard, professor of philosophy at Aberdeen, in 1791 and 1793; and James and his wife Marjory had their portraits painted by Henry Raeburn, paintings which now hang in the Frick Gallery in New York.

The Boblainie papers held by the Highland Council Archive contain thirty letters from Thomas Fraser, also a carpenter, from Inverness who was also in St Vincent and who knew the Cruikshank brothers well. In 1777 a Donald Cruikshank carried a letter home for Fraser, who used James Cruikshank in Kingstown, St Vincent, as his return address; in 1782 Fraser shared the cost of postage by enclosing his letter with one sent to the Cruikshanks’ parents at Gorton; and in 1790 he sat at the same desk as one of the Cruikshanks as they both wrote home. But although Patrick Cruikshank had been a carpenter like Thomas, by 1791 he had an income of three thousand pounds a year from a plantation, shared with his younger brother James. As Thomas saw it the difference was that ‘for some people their friends were here before them otherwise they might be toiling and working for other people to this good day as I am’. It was the two younger brothers, Alexander and John, who remained in St Vincent during the troubled 1790s.

at Gorton; and in 1790 he sat at the same desk as one of the Cruikshanks as they both wrote home. But although Patrick Cruikshank had been a carpenter like Thomas, by 1791 he had an income of three thousand pounds a year from a plantation, shared with his younger brother James. As Thomas saw it the difference was that ‘for some people their friends were here before them otherwise they might be toiling and working for other people to this good day as I am’. It was the two younger brothers, Alexander and John, who remained in St Vincent during the troubled 1790s.

On the morning of 14 March 1795, shortly after the Second Carib War had begun, the Carib chief Joseph Chatoyer had three British prisoners brought before him – Duncan Cruikshank, Peter Cruikshank, and Alexander Grant. Using the sabre which had been presented to him by Sir William Young to mark the peace treaty of 1773 which ended the First Carib War, Chatoyer hacked the three men to death. It is possible that these Cruikshanks were relations, possibly cousins, of the brothers from Gorton.

The Caribs were defeated in 1797, although some resistance continued until they were deported from the island in an act which can accurately be described as one of ‘ethnic cleansing’. In February 1797, 4336 defeated Caribs – 1002 men, 1779 women and 1555 children – were disembarked and confined on the tiny island of Baliceaux ten miles south of St Vincent. Exhausted, crowded together, and exposed to a variety of infectious diseases, they began to die. When HMS Experiment arrived with other vessels in March to transport them to the Spanish island of Roatán in the Bay of Honduras, only half of their number were still alive.

In June 1804 an Act was passed by which the Caribs formally lost their rights to their land and which allowed the Governor to sell these to British planters. The largest tract of 600 acres was bought by John Cruikshank and other purchases included that by his brother Alexander Cruikshank, who acquired 300 acres. A number of these estates later sustained substantial damage through a violent eruption of the nearby La Soufrière volcano in April 1812, an event which was sketched by a local planter and became the subject of a powerful work by the artist J M W Turner in 1815.

In June 1804 an Act was passed by which the Caribs formally lost their rights to their land and which allowed the Governor to sell these to British planters. The largest tract of 600 acres was bought by John Cruikshank and other purchases included that by his brother Alexander Cruikshank, who acquired 300 acres. A number of these estates later sustained substantial damage through a violent eruption of the nearby La Soufrière volcano in April 1812, an event which was sketched by a local planter and became the subject of a powerful work by the artist J M W Turner in 1815.

A well-planned and effective campaign on behalf of planters with estates to on both the leeward (east) and windward (west) coasts in the north of St Vincent led to the setting up of a select committee of the House of Commons, a report to Parliament, and the award of £25,000 in compensation. Twenty planters claimed to have suffered losses which amounted to just over £79,000, although it is thought that these claims exaggerated their actual losses. Of the claimants at least eight were northern Scots – including James, Alexander and John Cruikshank, and Alexander Cuming, who was the Cruikshanks’ brother-in-law.

Alexander Cruikshank later bought the Scottish estate of Stracathro from the heirs of his brother Patrick, who had died in 1797, and in 1824 commissioned the Aberdeen architect Archibald Simpson to build him a Palladian mansion house, surrounded by a deer park and gardens. It is reckoned Simpson’s finest work and was a modification of a design he originally proposed for university buildings, in Corinthian style, on the site of Aberdeen’s Marischal College – a plan which was deemed too expensive.

Before 1817 Alexander had acquired plantation Hague in Demerara, which in that year had 646 slaves. In 1836 he received compensation of £32,640 for the emancipation of 620 slaves on Hague and another plantation. Despite being among the largest slave-owners in the colony, his financial position was soon such that he felt it necessary to return to Demerara, where he died in 1846 shortly after having advertised the sale of Stracathro. Patrick Cruikshank, the son of his brother James Cruikshank of Langley Park, successfully claimed £21,294 for the emancipation of 845 slaves on plantations in St Vincent.

Before 1817 Alexander had acquired plantation Hague in Demerara, which in that year had 646 slaves. In 1836 he received compensation of £32,640 for the emancipation of 620 slaves on Hague and another plantation. Despite being among the largest slave-owners in the colony, his financial position was soon such that he felt it necessary to return to Demerara, where he died in 1846 shortly after having advertised the sale of Stracathro. Patrick Cruikshank, the son of his brother James Cruikshank of Langley Park, successfully claimed £21,294 for the emancipation of 845 slaves on plantations in St Vincent.

Both Stracathro House (above) and Langley Park (below) remain as visible legacies of the fortunes made by the Cruikshanks of Gorton.