Tata Colin

Tata Colin [c1806-36] was an enslaved man on plantation Leasowes in Surinam who inspired and led an uprising of enslaved people in late 1835. He was tried in Paramaribo and condemned to death by hanging but died in his cell before the sentence was carried out

Tata Colin [c1806-36] was an enslaved man on plantation Leasowes in Surinam who inspired and led an uprising of enslaved people in late 1835. He was tried in Paramaribo and condemned to death by hanging but died in his cell before the sentence was carried out

In 1984 a statue of Tata Colin was erected at Totness, the principal settlement in Coronie.

Philip Dikland summarises much of what is known historically of Tata Colin in his account (in Dutch) of plantation Leasowes. The information given by Dikland is as follows:

The news that slavery was to be abolished in British Guiana in 1833 quickly spread through Suriname, especially in the Nickerie district, of which Coronie formed part, and these rumours led to unrest. The English and Scottish planters in those districts were afraid that things would get out of hand and looked for reinforcements.

In May 1832 the slaves at Leasowes danced on the dam in honour of the spirit Watra Mama [Queen of the River] and refused to work. After some of them were beaten and chained, order was restored. From that moment the instigator, Colin, remained dumb and did not speak again until the end of 1835.

Then he began to sing, set his hut on fire, and was then locked up in the plantation sick bay where at night he secretly received his followers. Colin preached liberation, which would be through a flood in which the whites would be drowned. When a dam did burst the slaves placed even more more value on Colin’s prophecy. These followers committed themselves unconditionally to Colin but some other slaves did not agree with his plans and betrayed him to the whites. Those who informed on him were George of Leasowes, and Evan of Burnside. George was rewarded with a silver medal, and Evan was manumitted by the government.

Ten slaves were arrested and interrogated for five days at Burnside. They were then taken to Paramaribo, convicted, and sentenced to death or years of hard labour. The judgment given on the black prophet of Coronie was death by hanging but Colin died under unknown circumstances in his cell, probably in Fort Zeelandia.

According to Wim Hoogbergen ['Marronage and Slave Rebellions in Surinam' in Wolfgang Binder (ed), Slavery in the Americas (Wurtzburg, 1993), 165-196] Colin's prophecies included that the sun would shine at night and the moon by day, blacks would become white and whites would become black and work as slaves. Colin 'spend his nights dancing and amusing himself with sexual extravagances' as he waited for these events to happen.

According to Wim Hoogbergen ['Marronage and Slave Rebellions in Surinam' in Wolfgang Binder (ed), Slavery in the Americas (Wurtzburg, 1993), 165-196] Colin's prophecies included that the sun would shine at night and the moon by day, blacks would become white and whites would become black and work as slaves. Colin 'spend his nights dancing and amusing himself with sexual extravagances' as he waited for these events to happen.

The fullest account of Tata Colin can be found in J Voorhoeve & H C van Renselaar, 'Messianism and Nationalism in Surinam', Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, 1962), pp. 193-216. These authors both consulted the trial papers and gathered oral traditions in Coronie in 1959.

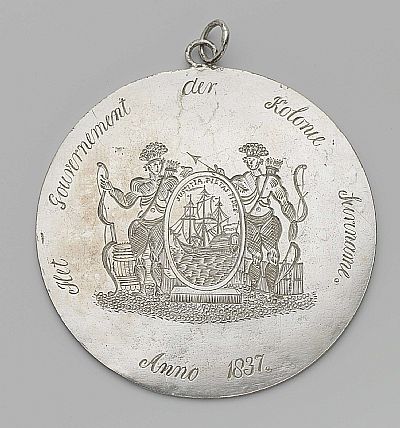

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam holds a silver medal (right) given to the slave George, who warned his master of the planned revolt.

In 1982 the Surinamese writer Ruud Mungroo published a novella about Tata Colin and the rising. To read an English version of Tata Colin (Paramaribo, 1982) enter this address in Google transalate: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/mung003tata01_01/mung003tata01_01_0001.php

Plantation Leasowes

When he died in 1821 Alexander Cameron, from Invermallie in Lochaber (Scotland), owned plantations Burnside, Leasowes, Clyde and Oxford, all on the Coronie coast and with a total of 450 slaves. His heirs were his brother-in-law William Mackintosh, from Inverness, and Donald and Duncan Cameron, who were either his brothers or his sons. At the time of Tata Colin's rising, the plantation was managed by William Mackintosh.

It is likely that Colin was born on neighbouring plantation Burnside, where his mother Maria was still a slave in 1836. In 1817, during Alexander Cameron's ownership, a Moravian missionary spend a number of months at Burnside and Cameron asked him to establish a church there. However, he withdrew the offer when other planters objected. Nevertheless, the preaching of the misionary, Mr Hafa, may have had some influence on Tata Colin as a boy.

One of Tata Colin's followers, the slave driver Greenfield from Leasowes, had spend 'several years in England with his master' [Voorhoeve & Renselaar, 215].