TECHNOLOGY in architecture.

When my father worked at the Council, I remember seeing great drawing pins holding down trace paper over originals for tracing. He had a collection of old drawing pens and I still have some of them. We had been taught how to use dipping pens in primary school (and later fountain pens), and these were little different. Quite archaic compared to the specialist drawing pens that had by this time come in such as that made by Rotring with its distinctive red band (hence the name). (Some of his older pens had been given to him).

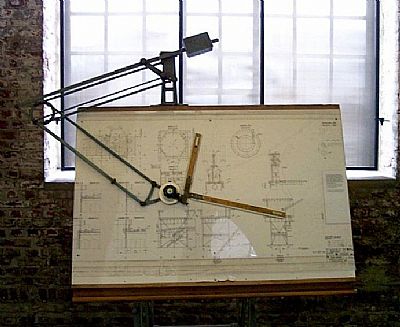

This was the era of the T-square although if you could afford it you got a "drafting machine". This was in reality really a set square in the form of scales set at right angles to each other and mounted on a large metal arm. This was fully pivoted so that any position and angle could be achieved. Cheaper than this was the "parallel motion" edge that was in essence a straight edge that reached right across the drawing board and could be moved up and down freely to any position up or down. When we started at university and even into first working in an office, we still used T-squares though.

This is a drawing machine from Google. You never think of photographing such things at the time.

Note that a "scale" is what you measure with. A "ruler" is the straight edge that you draw against to get a straight line. These are not the same thing, although the scales on the drawing machine were such that they could be ruled against. Otherwise you measured with the scale - in the chosen scale - marked it and then drew the line.

By the time that we had our own office in the 13th floor of the Murray and Stewart building in downtown East London everyone had progressed to masking tape. We even ventured to get a photocopier. A small, yet heavy A4 machine that needed 3 stages of original and then a positive and a negative. It got very hot, was awkward to use and was uneconomical. I think we donated it to the East London Museum, but would be surprised if they kept it.

I missed the era of "blue prints" although did see them about. At university we used a liquid amonia printing machine to get copies of our drawings. The positive drawn on tracing paper was laid over the sensitise yellow paper and fed through a UV light. It was then developed and fixed by passing it through the amonia liquid. A flexible tube led out through a window in an attempt to keep the working environment acceptable.

Our office though sent our drawings off to an office supplier shop that did printing as well.

We did the same thing when we moved to our new Devereux Avenue premises in Vincent. My father, always looking for savings, procured a second hand drawing printing box. First you needed to get the "negative" print by laying the drawn positive over the sensitised paper in the sun or at least bright light, preferably under glass to keep it flat. Then into the veritical wooden box into which you placed the loosely coiled "processed" paper. Then you poured liquid amonia into a saucer and placed that at the bottom, hoping that the vapours would process the sheet above it. All this was done while holding ones breath and then running for an open window, eyes smarting. It is hard to believe that we really did this. An archaic method even then and probably laughed at by anyone coming into the office at that moment. Naturally we resisted this and sent most of our drawings down the road for printing.

Our first professor at University, "Jeep" Snyman, had the foresight to get us onto a computer course - we before computers were generally available. So we learnt Basic and Fortran and Cobalt and other computer languages - without ever seeing a computer! When I did eventually see a real combuter a year later, I saw a set of 3. They were about the size of our kitchen fridge and located in the university library building. Large cassets spun on the front of each. The atmosphere was supposed to be completely controlled, but the flat roof of the futuristic library building, so recently built, already leaked and water cascaded down close by.

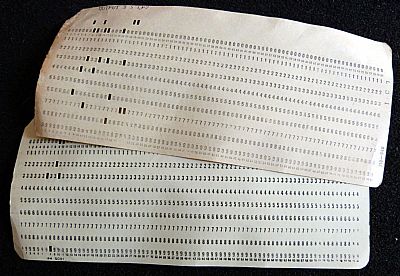

We did the computer course alongside students of othe disciplines and also did applied maths on the same basis. Two weekly tests were taken using multiple choice options on punch cards (monkey puzzles) which were then assessed by computers somewhere. Such was my introduction to the digital world just opening to us back then in the '70s.

I was reasonably good at some aspects of applied maths, but hopeless at others. I bought myself a battery operated calculator quite early on. But these were banned during exams as not every student could afford one. They used to chew up AA batteries very quickly.

Architectural drawings were done on drawing boards on stands which could be either spindly and cheap or large and expensive, yet adaptable in height and angle. Drawings were taped to the plastic overlaid surface. The drawing paper came in rolls and was either a transparent lightly textured surface or the more expensive, but more durable plastic. There were two typical drawing aids. One was a plastic horizontal straight edge on cables that kept it parallel. One then used an adjustable setsquare on it. At hand was a scale ie a ruler with various scales. The other was a large metallic arm that was fixed to the drawing board and had vertical and horizontal scales on it that were also used to draw lines against.

My father would be a stickler for neat lettering and new trainees would need to spend days practicing this. At one point he was offered a lettering machine, a forerunner of CAD, by George Albert, at great expense and was very tempted to get it. But by that time we were well into using stencils. Drawings began in pencil and were then inked to create clear plans for printing.

Errors and updated in drawings meant erasing the ink. If hand erasers did not suffice, old fashioned two edge razor blades were often used to take the ink off and this affected the paper surface too. We then needed to rub talc on to regain a suitable surface. Electric erasors were also used - a hand-held device with a spinning plug of erasor of selected abrasion. A small thin stainless steel sheet with shaped holes enabled more accurate and selective erasion. And a soft brush was at hand for all the dust.

If all of this sounds exhausting, it was. We once employed a young draftsman whos suffered from dyslexia. His father was the janitor for our 13 storey down town office block and he lived in a house on the roof. He was actually quite good. But one day we found that he had nearly completed a comprehensive drawing in mirror image. He had to redo it completely which took hours. (It takes mili-seconds to flip a drawing in CAD).

Drawings were usually done at A2 size or even up to A0. The old standard had been "double elephant" (26.7 x 40 inch / 678.2 x 1016mm). This had the great benefit (compared to the smaller printed drawings that subsequently became popular) of being easily displayed to the clients or on site for everyone to see. These large drawn originals were stored rolled up in the packet that the paper came in or in large wooden cabinets with several drawers or hung in metal cabinets with metal spike hangers, these drawings having had taped edges with holes to hang then with.

The design stage was usually done on light and cheap "butcher paper". It was usually referred to as "bumph". As a young stiudent I went into an office supplier to stock up on it. I was greeted across the counter by a new pretty assistant. She was blushed when I asked for "bumph". Being transparent, we could overlay and redraw or partially erase until we were satisfied. We used clutch pencils (not propelling pencils) as they could have leads of different thicknesses and hardness. My favourite at the early sketch stage was very thick.

Drawing and erasing

With the advent of CAD (Computer Aided Drafting came the ability to alter, duplicate, reposition, or simply erase. Back in my day it was very physical. Ink drawing was done with Rotring pens (red ring being their identifying mark). They came in a range of sizes and could be as sharp as needles. They clogged up easily and needed regular cleaning in a solution within a special container. They also broke or buckled easily if bumped and this happened rather frequently as we walked around or gesticulated with the pens upcapped. To counter this I would hold them back to front, but accidents still happened and I have some tiny "tattoos" on my hands where I jabbed the points into them if I bumped something while walking around.

Here is a collection of drawing equipment. The adjustable setsquare should look familiar. There are two French curves used to rule against for curved shapes, (these are identical, but there were various alternatives). There are eliptical and round stencils and one for sanitary fittings. There is one too for asbestos roofing sheets. And there is a brick scale for laying out your brick coursing which you may do in details of different scales - essential for neat layout of facing bricks between windows and doors or facier designs.

You drew in pencil and then inked over. If you needed to change something you used an eraser, but that needed to be precises so erasing shields were used to focus down on specific things. That produced a lot of dust, hence the brush. All that may not have been sufficient to remove a line so old fashioned razor blades were used to scratch off the waxy surface of the paper. To regain it, talc powder was rubbed on. This naturally could become a bit messy and damage the paper - and you drawing. Remember that prints then were made through the paper (not photocopied as in later years and not printed out direct from a computer).

Scale

A ruler is for ruling against while drawing even if it has a scale annotated on it. A SCALE is a tool for measuring to a chosen scale.

We had quite a variety of scales. There were still Imperial ones around as we needed to work off older drawings. Most drawings were done in 1:100 for general plans; 1:20 for details and 1:50 for things in between. But other scales were used too. In the photo you will see those with 1:1 (actual size), 1:2, 1:5, 1:10, 1:25, 1:30,1:75, 1:200, 1:1250, 1:2500. Something for almost any situation. Sometimes a consultant such as a structual or mechanical / electrical engineer or a land surveyor would use a scale you didn't consider normal and you needed to be able to work from their drawings.

You will notice that some are triangular - in order to squeeze more onto a single item. We sometimes got given them as trade promotional gifts. (Hyson - Cells were used to stabilise dune sands or gravel).

This was still a time when those of the old school still thought in Imperial scale and would need to convert in their heads or with the new fangle calculators (which only work in metric!). The Imperial scales included : Inch (actual size), 1:1/2, 1:1/4, 1:1/8.

When at primary school we were taught some of the already outgoing units such as roods and poles. Sometimes we would come across old drawings in the Council archive when looking for details of sites in the city laid out a very long time ago. I did see some with those units, but Cape Feet had been the main unit for site layout. There is a hardwood scale in the collection in this unit.

So if we were drawing in METRIC yet taking information off old drawings in IMPERIAL we needed a means of direct conversion. In amongst those scales are CONVERSION SCALES. These enable one to be directly measured in the other - Imperial to Metric. If you see very odd ratios such as 1:4, 1:8, 1:12, 1:16, 1:24, 1:32, 1:34, 1:48, 1:64, 1:96 1:128, 1:192, 1:360, 1:480, 1:720, 1:2400, these are conversion scales. The sharp witted amongst you may have noticed that some are doubled up.

A variety of scales.

Calculations

Computers discussed elsewhere. For the moment lets ponder how we did before CAD and even calculators.

Maths, trigonometry and geometry!!

There was always a notepad at hand. But we were not completely without a means of calculation. We had sliderules.

Fortunately for me calculators came in to general use while I was at university and were readily available at work, but I did learn to use sliderules. There is a nack to it, which I promptly forgot, but the principle is straight forward. Scales of different types are slid against each other to get answers. Everything is relative. Multiplication is easy, but it is possible to do quite complex calculations with the right knowhow.

Some sliderules.

Annotation

My father was a stickler for neat labelling and new recruits would sit for days perfecting it before getting involved in drawings. We generally recruited raw so these were young people with no previous training. Most of them though did get on with their careers even with other employers, with time with us as good grounding.

While my father was good at annotating drawings himself, his general handwriting was the mystification of secretaries - although our last one got to know his writing and his ways well. He would reuse past letter drafts by writing across the page at right angles to save paper.

While CAD was still in its infancy he was almost persuaded by a fellow architect, George Albert, to buy his "computer aided" text machine from him at great cost. This would be fixed to the drawing board and text typed in, whereapon it would write out the text onto the otherwise hand-drawn drawing. We in turn persuaded him otherwise. And eventually did get desktop computers. I quickly adapted my skills I had taught myself on the typewriter and did all my own letters, specifications and schedules from then on. I did not need a secretary.

But annotating drawings was still done by hand. However with this we did have the benefit of lettering stencils - one for each pen size.

Some of the lettering stencils. With skill these could be used quite briskly, sliding them along the parallel motion drawing machine.

Computers

Many practices, both architectural and engineering, jumped on the CAD (computer aided drafting) pretty promptly. We held back, mainly due to the expense. This was not just the computers themselves, but the software licenses and printers. The use of just A3 print outs were becoming popular and often issued as portfolios.

However I did follow the evolvement of CAD locally through attending trade shows and seminars during the 1980s. Two names stand out. One was that of the Skok Brothers who seemed well in the forefront internationally, at the time. (I still find that name when associated with machine tools in South Africa and presume that this evolved from that time). The other was Allyson Lawless who developed AllyCad aimed at engineers.

They used to boast that they could accomplish curves at a good scale - something taken for granted now. Engineers seem to adapt to CAD mor readily than architects as their drawings were more skeletal than those of architects. I would watch their drawings being printed, a process that took ages with pens of 3 primary colours jumping accross a sheet itself darting over a roller. Clever and fascinating to watch, but unconvincing to me to take on. We would wait until things improved.

Besides the cost of transitioning to CAD was the downtime that would be needed to train and be trained. By this time, at least locally, CADDIE was becoming the preferred choice by architects.

It was a big enough upgrade when we acquired a new typewriter that had a tiny screen that showed the few words being typed. And at times we had either a rose or a golfball type writer. Remember those?

I taught myself to type and needed the secretary to prepare documents and letters for me less and less. So when we did eventually acquire some computers I could do all that myself. I did an intro course to CAD and attempted to do door schedules on it, but found that awkward. Generak correspondence, specifications etc were fine.

We acquired 3 computers. One each for me, my father and the secretary. We were down to one draughsman and he brought his own one in. And they were all stolen one weekend. Workmen had left scaffolding uo outside the window and I had failed to repair a window catch.

We replaced them and continued.

By the time we got into computers, they had already evolved quite a bit.

Computer memory.

It is funny to think back to when we had floppy disks. We then progressed to stiffies. In retrospect with CD-ROMs coming in, there was often confusion between these two, later stiffies being by comparison also floppy. Computers did have their own memory capacity, but it was limited. And we were still some way from having the ability to store on cloud.

Also see TECHNOLOGY in communication & entertainment

But by then I was nearing the point at which I needed to work from home.

I did small jobs and emailed my drawings as pdfs to printers in Paisley where I picked them up.

The amazing ability to transmit images & text over the phone line.

I should at this point also mentioned our fax.

We bought one second hand from a local political party and tended to get some of their messages on it.

When I applied for temporary residence in the UK I did so under the Ancestry route instead of the Marriage route, although some questions seemed to overlap. The form was lengthy and took all night to come in by fax. A continuous coil of paper greeted me on the floor the next morning. (The UK wary of arranged marriages, asked "Have you met your wife yet?).

Building in South Africa is much cheaper than in Scotland. Not only due to labour costs, but there is less need to insulate against the cold. It is more likely a case there of insulating to keep the heat out and retain a cooler environment. But then it is also a lot less sophisticated.

Scotland's building regulations are even different to the south of us in England and this has a lot to do with efficient building systems and their insulation. So much is led by the R-factor. (In construction, the R-value is the measurement of a material's capacity to resist heat flow from one side to the other. In simple terms, R-values measure the effectiveness of insulation and a higher number represents more effective insulation. R-values are additive). And then there is health and safety, disabled access etc etc. I only once had to wear a hard hat on a building site in South Africa, while here it is essential, and high viz clothing, and safety boots........

University

The subject of university is somewhat out of sync with the above, but it gives me an opportunity to tell you something of my course, aspects that are within the subject of technology. I found aspects of it easy and others very difficult. However there were some highlights.

Our first professor had the foresight to put us on a computer course way before they were the norm. In fact I had not yet seen a real computer even by the time we finished this year long course. But we did do computer programming such as Fortran, Cobalt and Basic. Very simple in principle - computers cannot count beyond "0" or "1" even now, but work on the principles of batching these two options in various ways. It was that which really confused me.

The university (not yet the architectural department) eventually got a set of computers, large fridge sized things as mentioned above, with large whirring cassettes and I got to see those.

We also did "applied maths" which I enjoyed to some extent, but in which I then got out my depth. We did it alongside students of other disciplines and the content range was wide. Everything from the deflection of beams under dead or live loads before failure to the vectors of aeroplanes in wind of different angles and strengths.

By this time I had my expensive calculator which I used for homework. The AA batteries didn't last through an evening doing this. (No rechargeable batteries then).

In spite of that subject complexity, the maths department had to get time assigned on the main university computers. And then things were very basic. We had weekly tests with multiple choice answers; the most efficient way to run them at the time. So we sat there with "monkey puzzle" punch cards selecting the chosen answers. We had an overlay template to enable us to see the question / answer locations and we would then push through with a pencil.

Monkey puzzle cards with the perforations. These would be sent off with our class ID numbers and fed into the computer much as we put a bank card into a ATM these days. The difference here is that the cards just have holes and no electro magnetic strips.

Early computer card readers were base on electromechanical unit record equipment and used mechanical brushes that make an electrical contact for a hole, and no contact if there was no hole. Later readers used photoelectric sensors to detect the presence or absence of a hole. [Wiki].

Scotland

When we emigrated to Scotland I did a crash course in CAD. By this time AutoCad was the popular choice. When I first began to work here I had not quite completed the course and pretty much learnt as I worked. But I got reasonably proficient at it. Working with layers, different line types, colours, hatching etc was standard routine. We could overlay, import, share across disciplines and with contractors quite readily. I was happy with that until the more sophisticated 3D CAD work became a bit challenging. I was working in large offices, the last one being multidisciplinary.

Towards the end that practice was sold and I was one of the older members of staff, proficient in what I was doing in architecture, but not as adaptable to techniques such as for measuring the energy efficiency of large buildings.

However I did do quite a bit of building survey and drew up the surveys of others as well. Most of this was for Edinburgh Council's property audit. Absolutely exact and detailed drawings were not needed, but they were required to reflect otherwise unrecorded changes of the years. To achieve as much detail as possible, I used Google Maps and Street View; services unimaginable when I started my career.

Our South African offices

I have by now experienced a variety of architectural working environments, both in SA and in Scotland. It may be of interest to note those before we emmigrated.

East London Council : My father was a principle architect for the council before setting up his own practice.

South African Permanent Building Society : The building society leased out offices above their Oxford Street level public areas. My father started his practice in such premises and I would go in during the holidays to help eg colour coding drawings for submission to the Council. My mother served as the secretary.

Murray and Stewart Centre : The practice then expanded into spacious premises on the 13th floor of this building with great views of the city and even out to sea. We would watch the gannets diving during the sardine run with the office dumpy level (survey level). These were my student years and I worked there during the holidays. I always hated suits. My father was alway formal. A compromise was to wear "safari suits" (shorts and socks), which at the time were popular. One of my pranks was to climb out of a 13th floor window and suddenly appear at another further down the office. This rarely failed to startle new staff. They didn't realise that there was a window cleaners' gantry right around the building. One of our staff lived in a house on the roof. His father was the janitor for the building.

After several years there, my father decided to build his own premise in Devereux Avenue in Vincent. He went into a property partnership with the next door service station owner and a builder who already used a house there. "Treble - B". A two storey building was added in front of the house up to the street with a small courtyard linking through. We took the upper floor. This was also the time when we were building our own house, so I had only a little to do with the design of these office premises.

Our entrance steps to our Devereux Avenue offices. I had gleaned a classical pilaster capital from a building being demolished down town and had it mounted onto a purpose cast half-width column set on a cut paving slab. I then "marbled" it myself.

ALLYCAD : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allyson_Lawless

SKOK : https://www.skok.co.za/

WIKIPEDIA : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punched_card_input/output