POLITICS & SECURITY

In South Africa, these two subjects are much more entwined than in Scotland where we live now.

As with my other topics, this is a record of my personal contact with, not really involvement in, the politics of the country and does not attempt to analyse it very much. It has to be admitted though that politics has shaped my life, provided the background to it, even my active involvement in it has been peripheral. My ancestors had arrived in South Africa either within the large scale settlement of British settlers in 1820 to expend the Empire and offset the black incursions into the Colony or as later immigrants encouraged in later years for similar reasons.

Some of the subjects discussed below tend to overlap in time, so you may notice some that appear a bit out of sequence, but I have attempted to set them out in the most readable way.

My parents never talked of politics, but growing up I was aware of it in some ways. I have mentioned elsewhere seeing the house maid of the house behind us in Baysville being arrested for theft and hearing her saying it was right to steal as she had nothing and they had everything. I have mentioned the bush dwellers near where we played when very young and seeing a body being removed. I have mentioned how most whites called most blacks “boy” or “girl” no matter their age. Not necessarily through any sense of dominance or hatred; often simply a paternalistic superiority. And black folk had a quiet acceptance of the status quo and their roles in life – well that is the perception we were presented with. Almost all of them were subservient. Generations had grown up and grown old inherently feeling their dependence on whites for employment; for almost everything.

This was cringingly embarrassing to any white liberal, but habit entrenched it for all. Change was to take a very long time to occur. - But we are jumping the gun and must take ourselves back in time to when I first became aware of all this.

The degree of a sense of prejudicial superiority whites felt was considered to be less by the English speakers than by the Afrikaans speakers; the latter after all had formalised apartheid. The latter were so much more tied into the ruling government of the day and therefore supporting the doctrine of the National Party. The South Africa was declared an independent sovereign state in 1934, but it remained in effect a self-ruling colony of the United Kingdom for years to come.

My maternal grandmother, Nana, had not seen her country of birth, Ireland (Belfast), for decades, but retained her strong Irish identity. However it was my paternal grandmother, Maud, who had been born in SA and had only briefly seen England, that perhaps epitomises white colonial thought. She had lived in East London (SA) and for some time with her farming sons in Southern and Northern Rhodesia. While living with us years later she had what appeared to me, the quirky insistence that we stand up for the God-Save-The-Queen music that came out of the SABC radio service as it closed down each evening at about 10pm. There was, and to a much lesser extent still remains, a feeling of belonging to a much greater entity – mainly by English speakers with the UK or perhaps other European connections.

In 1961 SA declared itself a republic completely independent of the UK. I was midway through primary school. I remember the build-up to the referendum and the mood building up to it. At this young age I was beginning to be more aware of South African politics. I was beginning to hear talk, mainly by the parents of friends, of apartheid, of the Sharpville Massacre....... I can remember that even at the age of 10, I had discussions with my young friends at school of emigrating in case life here became intolerable. I chose Canada. My parents still hardly spoke of it all. I was picking this all up from school and from families of friends. Then the day of Independence arrived. At primary school we got little versions of the new flag and a celebratory coin and cool drinks and sweets. A happy day for us young people. I lost the momentos.

Life continued much the same. At Sea Scouts we still did Baden-Powell stuff. We still found reference to God and the Queen in our handbook and events although as reprints came in that slowly faded. I lingered in scouts a bit longer than was probably good for me although being rather reserved, I didn't have alternatives to get me out and about. I got my chief scout award. My father became involved in the troop and as a district scouter. We came across non-white scout troops at our regional camps, but they did not camp alongside us as, I was to understand much later, law prevented that. My father was somewhat conservative, but with a paternalistic outlook. He brought home a coloured scout master one day for lunch. As we dropped him back at the station he walked through the “whites only” door. I was very concerned that he was breaking a law. I had not yet developed a clear head and resistance to such things.

I attended a jamboree in Pretoria coinciding with Republic Day. The Voortrekkers (the Afrikaner equivalent of scouts) camped nearby. We found them rather militaristic. This was concurrent with the Republic Day celebrations and we watched as Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd (the "architect of apartheid") drive by when we attended the public events in Pretoria Heights.

The navy exposes me to wider politics.

I had hoped for a career in the navy and managed to do basic training at Gordons Bay on False Bay. This was the same place that officer training took place. See NAVAL CAREER, English and Afrikaans together. Mild “Boer War” jokes and rivalry. With me was a guy who was descended from Messerschmitt, the German WWII fighter plane manufacturer. I did not get onto the officer course. I was too timid and could not name all of the government ministers. I was beginning to realise how insular my life had been.

As the officer candidates from other centres arrived and before many of us left for other courses elsewhere I met some of them. One was Paul Vorster, son of the then prime minister. I was still very naïve about politics. I noted that this naval base had some non-white employees that blended in well. One was a driver. Another a tailor. Both coloured in the sense of the word then standard.

After a spell on a ship where I got asthma I was moved to Youngsfield – a combined army/navy/airforce base. It had a very basic airstrip and was used for accommodation and some flight training. The navy used it as Maritime Headwquarters (Silvermine state of the art HQ being still built). We plotted the shipping around the coast based on surveilance aircraft reports including the many Russian cargo ships carrying military trucks and tanks destined for other countries. The location suited me as it was in easy contact with my Rondebosch Watson cousins, and it was fairly easy to go into Cape Town. Once, to save bus and train fares, I walked from Cape Town back to the base. I passed through the fascinating area of District 6. People of all races and faiths living in bustling proximity. Flats above businesses. Happy, Moaning. Cajoling. Bidding. Calling “hey sailor” to me from balconies. I was in full uniform. I loved it.

It was years later that I got to understand District 6's predicament; how it had already been shrunk under apartheid. It is gone. Similar fates met mixed communities around the country including in Port Elizabeth and East London - all in the name of "improvement", but all politically motivated. If you are reading this from a time and place that this makes little sense you will need some explanation.

This was 1970 and Apartheid as a formal doctrine was being enforced. This meant forced separation of the races. Cape Town and its environs had fewer "black" people back then; the predominant non-white race was "coloured". These were folk who had evolved from indigenous Koi (Hottentots) and imported Malay slaves. Added to the mix were some white half-breeds and some Indians. This was all very complicated. However they had developed a fairly distinctive identity and culture and got on well with each other. Some were Christian and some Moslem with mosques.

The government decided to eradicate all areas of races other than white from within what it deemed white areas. This was done forcibly - with bulldozers. [While similar stories occured elsewhere to separate out black areas, that of places such as District 6 are distinctive]. I was privileged to have seen it before that destruction. At that time I was not aware then of its impending fate.

Almost everything was flattened. The only few buildings left standing were some mosques - saved through an appeal to the United Nations. They were singled out as sacred. It did not save their adjoining environment and they were left for a long time amid the desolation. The resultant flattened areas were then made available for white development with incongruous mosques, many still used, within them.

I did not realise at the time, but my conscription as a young white man had given me this opportunity.

University

With the navy out of the way, I was off to varsity. The University of Port Elizabeth. Bilingual. Created to offset the liberal presence of Rhodes in the city (although centred in Grahamstown). Created by the secretive Broederbond. Dominated at Board level by Nats and Dutch Reformed Church members which were completely entwined. But it did have a new architecture school and it was relatively close to East London. My academic record left a lot to be desired for, but the whole experience did influence me in other ways. I remember a dominee student going amongst the participants at a dance and forcing couples from his congregation apart. I remember a dance between students from Rhodes and UPE after a major sports event being cancelled because Rhodes had Chinese !!! students. It was that which startled me into joining the Progressive Party. I was certainly not political material, being reserved and shy, but I did get to be youth chairman (with very few young members).

At this bilingual university I found that those of Afrikaner stock were generally very politically aware, while those who English speakers were generally very complacent. It was heartening to come across Afrikaans speakers who, may still support apartheid, but nevertheless recognised a need for change in the then not too distant future. Even those with a father with Broederbond membership and on the University Board. I targeted some of these and arranged for them to have the Afrikaans language magazine of the Progressive Party. Some of them were studying politics and found this of interest. I feel that I made some small impact this way.

While a student I canvased for elections for Andy Savage (Only in later life have I discerned a shared family connection through Ancestry.com) and Paddy Ball. I did meet Colin Eglin and van Zyl Slabbert and Helen Suzman and they made quite an impression on me. The party changed name as the Union party disbanded with some members joining us. It lost a bit of its righteous and idealistic oomph, but remained much the same.

On leaving varsity and starting work I joined the East London branch of the party. I canvassed there for John Malcomess (who owned the Mercedes francise in the city). While canvassing, I was still coming across women at the door who had not yet been told by their husbands what to vote! I met some of the old stalwarts again and a new politician, Marius Barnard, brother of Chris Barnard. They had both pioneered heart transplants (and had operated on my wife's aunt - not a transplant).

By the early '80s I had tired of politics as such and sought something more practical and pragmatic. I joined the South African Institute for Race Relations. Its local director was Val Viljoen, a lovely and forthright women who could confidently handle the occasional radio interviews by visiting reporters from the Netherlands, Denmark etc. (She was to become an MP in free South Africa). The chairman then was Harold Winearls; a lawyer. He had his post box blown up with a stolen army thunderflash. A prank? Or a complaint against his liberal politics? Next was a church minister, Steve Fourie. (We had Steve officiate at our wedding at the Clarendon Road house). I became active on the committee.

The SAIRR had a shop at street level with books and local crafts and a catch-up school upstairs for the many of olther races who did not get decent education. This was in premises across from the City Hall. The security police would occasionally pounce and take away things such as calculators (then quite expensive) and subversive children's books such as Molo Songololo (Hello Millipede). Working for the Institute was E who was concurrently doing postgrad research, much of which was oral histories on tapes. The committee met in the shop window in full sight of passers-by. Her car with all her research was out of sight just slightly down from us. Once when we came out the car had been broken into and almost all her research material had been taken; not loose cash. It could only have been the security police. I drove her in the dark around Duncan Village to look for anything that may have been jettisoned. It could have been absolutely anywhere, but the through road was a possibility and we simply had to do something. It was never found and she had to a great deal to do over again.

As the chairman's term came to an end at an AGM, the small committee stood around afterwards to select the new chairman. It was me. The very next morning I had a phone call inviting me to a restaurant (owned by the Daily Dispatch) for lunch by a security policeman, Dirk Pruytt (?). I agreed to go, but refused to have anything to eat and sat there watching him eat while answering mundane questions. He was evidently simply making sure I understood that they already knew everything. He said he knew me from school. I didn't remember him.

It turned out that we had a telltale within our small committee. Pam. I was the only one who had not already known. She worked for the Daily Dispatch. Her husband was a policeman and in turn in contact with the Security Police. We grew suspicious of phone calls after that and suspected tapping. I was later to meet a government building inspector on one of my jobs who acknowledged that the Security Police would sometimes use his department as a front for phone tapping.

The Border War

South Africa's Border War was ironically not fought on the border of SA, but in Angola. It had great significance for Namibia which was then still South West Africa and under the Mandate of South Africa (something lingering since WWII when it was taken from German control). While in essence independent, the shadow of South Africa's racial policies hung over it and it was seeking independence.

Perversely, it got very intertwined with the Angolan civil war and Zambia also got involved. It occured between 1966 and 1990. The South African Defence Force included mainly conscripts so we naturally found young local men being called up (with some deaths). Our architectural practice would need to deal with staff away "on border duty" and we would hear of some stories when they got back. There was the case of one of our staff hearing sounds in the dark outside their camp when on duty. There was not answer when it was challenged so he shot. And in the morning found a dead donkey that had been grazing nearby. Another told of soldiers in the back of a Bedford troop truck going over a landmine. The blast was small, but one died when his head hit the metal bar above him.

Generally though all the action was across the border into Angola and South West Africa as it was then quiet. It was during this period that I travelled with a friend of mine from university up by car most of the length of the country to Etosha. We saw some military vehicles and a small spotter plane, but no other signs of a military campaign. But we did discuss the possibility of landmines on the public roads ... just in case.

In later years I was active in the SAIRR, the South African Institute of Race Relations. The war naturally came up at national meetings. One of our members was a young major in the army and he told of what I subsequently got to know as "false flagging". I wondered why he supported the SADF while knowing about this (and was otherwise liberally minded), but he said that he still had a duty to defend his country if was attacked. Some of us wanted to give these lies more publicity. He replied that this would put more of our own troops in danger.

There were basically two factions. One that SA supported and was fighting alongside and those against. Quite which was the most ethically in the right depended on your background. That after all is characteristic of all wars. SA was in essence fighting to preserve its hold on South West Africa and supported the side that supported it. And that meant racial policies too.

In essence there was UNITA under Jonas Savimbi fighting to get indepence from Portugal. And SWAPO fighting to free South West Africa from SA. The fact that almost all the conflict was kept north of the border indicates the balance of power.

Both opposition forces gained support from Russia which also supported those seeking to overthrow the the SA apartheid regime.

SA threw in its weight with UNITA as the chosen side; something that in retrospect seems incongruous. But the USA was also on the scene. They had significant investments in the small enclave of Cabinda on the coast with its good oil reserves. This was the winning side - militarily.

Those against the SA government found support from Russia both here in Angola and elsewhere within Africa

Angola was under Portuguese control state but when independence was given this small enclave was retained - with the resultant controversy and tensions. It was all quite a political mess, but overall is now peaceful. South West Africa, now Namibia, was given its independence from SA in 1990 and is a wonderful country to visit.

Duncan Village

Also see DUNCAN VILLAGE for photos of this area at the time.

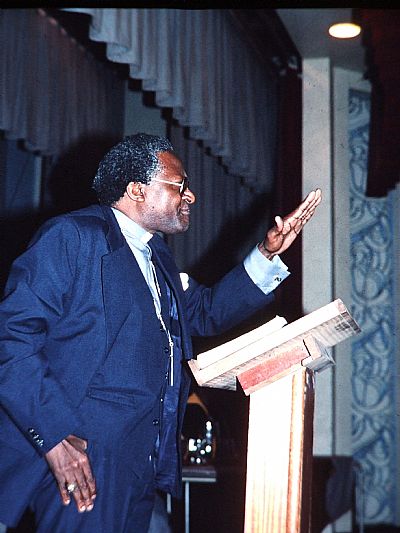

Duncan Village was a suburb within East London that had been created as a residential area for other races, mainly black. Buffalo Flats beyond it was newer and for coloureds. The sprawling township of Mdantsane had been created beyond the city boundaries for blacks as part of the apartheid doctrine. So that meant blacks would be enticed to leave Duncan Village or as housing was made available in Mdantsane, forced to go there. Coloured and black folk had lived amicably in Duncan Village for generations. But accommodation was very limited. On one occassion I even visited shanty houses built over graves. With the prospect of being allocated housing vacated by black folk, coloured people's hopes were raised and tensions arose. The Institute lent their support to a group resisting this segregated reallocation on apartheid lines. I arranged for a sympathetic academic town planner Prof Wally van Zyl from Bloemfontein to come down and address a public meeting. This was well supported. We had the amazing Bishop Tutu as key speaker. I, though, reserved, still nervous about the security police and with a new family to care for, would not chair the meeting and instead got the preceding Institute chairman, Harold Winnearls to do so. He was after all a lawyer and more experienced. I never got to actually meet Tutu although I did take photos.

But I did vaguely get to know his wife Leah. As regional chairman I also served on the national board. Familiar faces such as van Zyl Slabbert were there and I met some other amazing people, mainly academics from around the country. Both van Zyl Slabbert and a Natal academic had their personal libraries ransacked and torched, presumably by the security police.

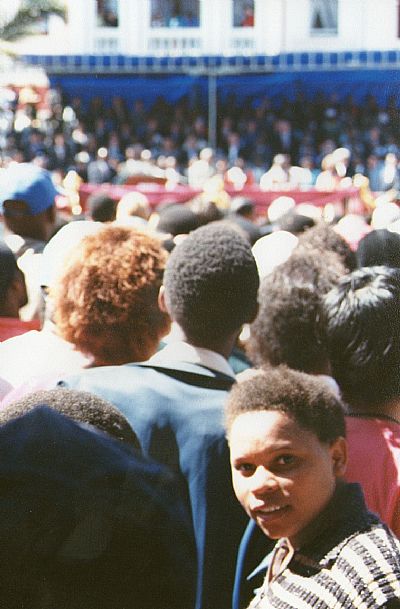

Desmond Tutu in full flow.

A group at the Duncan Village community meeting with Desmond Tutu.

It was at this time that moves were started to create Operation Hunger. I was on the subcommittee with Leah Tutu. My initial expectations were in hindsight very naïve. It was to get a full time director and the efforts grew dramatically. But even her perceptions were shown to be too reticent, she was replaced and it grew apace. The main drive was to meet the terrible hunger and malnutrition created by the conditions that apartheid left in many regions. The demise of apartheid did not resolve that at all, but it did affect the means and efficacy of the charity and it was to fade from prominence.

During the years up to and even a little after the end of apartheid we also did some pre- and primary schools within Duncan Village and on the northern edge. It was when the new President of Ciskei, Oupa Quoza officiated at the primary school that I met him. By this time the firmly defined edges of the Republic of Ciskei and the outer edges of East London within SA were becoming a little obscure.

Duncan Village remained occupied by Black and Coloured people. On returning from a site visit there one day I found myself at the front end of an approaching march heading towards the city centre. These were all toy toying black folk. Some large troop carriers of the SA army were at the ready on the main road, sheepish young white conscript soldiers peeping out the top hatches. In between were some East London municipal police. [There were then national SA police with its own subdivisions, provincial police and localised municipal security squads]. I recognised Graham Moore, who I vaguely knew, in charge and he talked the leaders and he waved me on. The mood wa actually quite amiable.

Ciskei

While Wally van Zyl was in East London I suggested that he join me at the Independence Celebrations for the Republic of Ciskei. I had been invited as I had been doing architectural work there. We sat in the stadium close just up from the new President Lennox Sebe. There were the usual speeches and military pomp – on a modest scale for a new country. And then the South African flag was lowered with drums and bugles. At this moment the Ciskein soldier tugged the flag of the new Ciskei republic. It wouldn't unfurl. He tried again. And again. Surely a hard yank would do the trick. The whole flagpole collapsed and broke in half. Some SA soldiers came across and tied it together using the flag rope and with a now much shorter flagpole but with at least a flag flying, the ceremony continued. Now if I was superstitious......... It was by now well after midnight which was the alotted the time of the changeover. Wally and I crept out – to be met by many other vehicles leaving early. We were hit quite hard by a Ciskei Department of Health bakkie. Fortunately for me it caught the turned left tyre and only scratched the mirror. Unfortunately for Wally, he didn't have the benefit of a steering wheel to grab and he had whiplash for a long time afterwards. Well the history of the Republic of Ciskei was short but calamitous; sometimes simply inept; sometimes violent.

I was to meet the President of the Ciskei, Lennox Sebe, once at an East London library function when he launched his book - a lot of boring past speeches. Other than saying hello, we didn't really talk to each other and I remember him standing there alone and lonely afterwards, ignored by everyone. Perhaps I should have chatted to him. He was afterall part of our history.

When doing work in Mdantsane which was becoming part of the independent homeland of the Republic of Ciskei I first needed to get a permit from the SA run office on the approach road. I didn't always bother.

We did a number of Government Workshops in Ciskei deputised while still initiated through Pertoria. But although the funding was from SA, it was handled through Ciskei offices at first in Zwelitsha and subsequently in the capital Bisho. As the postal service could not be trusted I had to go to fetch our fee cheques. The Zwelitsha office was a rabbit warren of prefab and similar old buildings congealed together. Sometimes it did not bother to open. On one occasion when they, the Department of Works, had become behind in its electricity payments, it had been cut off. What natural light was minimal and limited to the outer offices. Fortunately the official found it in a filing cabinet with a torch. The Bisho offices were much better. In fact Bisho had some quite impressive new buildings.The officials were eventually getting the hang it. I needed to witness tender openings for instance, that of the Mdantsane Post Office discussed below, there. I have a strong memory of Kentucky Fried Chicken everywhere. Finger Licken lunch all over the desks. It was said you got things done quicker if you gave some to the official concerned.

The Apartheid regime still had hold and asserted it forcibly, sometimes violently during the '80s. It is not the aim of this to get into the now historical details of it nor of the debacles parallel to it in places such as Ciskei, but a few comments are fitting. We scanned the more liberal English newspaper for factual news. It was not always obvious. The Daily Dispatch at the peak of apartheid would publish newspapers with large gaps to emphasise how gagged it was. Its editor, Donald Woods had fled. Years later a film had been produced based on his efforts to expose the reality behind the black activist Steve Biko's death in the hands of the police. “Cry Freedom' was directed and produced by Richard Attenborough. As we stood in the queue at the cinema in East London to get tickets, police arrived and seized the film reel. Coincidently we were soon to take a holiday in Scotland. We saw it in Clydebank. A very emotional experience. This was home grown politics and violence. And we even knew some of the characters depicted. Donald Woods's secretary had grown up down the road. A key policeman was Donald Card, whose wife had sold my mother home knitted jerseys for us when we were young. I had got to know Donald in later years as an efficient councillor and even mayor. But at the time depicted in the film he is cop caught up supporting the apartheid regime. He subsequently helped in the untangling of it. While I got on well with Donald when I met him at events or even popped in to his mayoral office about things, I never qutie worked out what his involvement had been as a policeman or of his later seemingly mellowed approach.

The government of Lennox Sebe fell in a blood-less coup to Brigadier Oupa Gqoza. While the coup itself may have been bloodless, the build up to it wasn't. I never really understood the politics and rivalries so will not get into that here suffice to remember the Bisho Massacre of 1992 in attempt to oust Gqozo. See link below. Burnt on the outside and raw inside. I do not like my meat rare, let alone still walking moments beforehand.

Apartheid did eventually crumble. But as it did so efforts were made on a number of fronts to speed it on its way and to set up the ground work for a new society. This was an unsettling period. Groups such as IDASA were making diplomatic forays into neighbouring countries to meet leaders in exile, And they would set up events locally to report back. On one occasion we met several very cautious local activitists. One was a women, Marion Sparg, white, who had set a bomb in the Cambridge Police Station toilets.

I remember seeing the bomb damage of three bombs in and near East London. All very small, but having a rebellious punch. One was outside the Golden Egg in Oxford Street. Another at the building used by Rhodes University in the lower city centre. The third at Mdantsane Post Office.

Mdantsane

Remember that while great progress was made at some levels in dismantling apartheid, leaders of “independent homelands” had their own issues and could resort to violence to assert dominance. My father had been the architect while working for the council for the Mdantsane Post Office, now within the republic of Ciskei. One day we heard that a bomb had gone off within it. I went to look. Minor damage. Fallen ceilings and a brick wall had shifted.

But then rebellion broke out against the Ciskei regime. ALL public buildings were set on fire plus a number of private businesses and some industries outside of the Ciskei boundaries in nearby Fort Jackson (roughly where our Miller ancestors had lived). I had been intending to go to the regional capital of Bisho to see the tenders for the bomb damage work, but hesitated for a few days. When I did get there, the whole of the commercial – administrative part of Mdantsane looked like something out of a Beirut war documentary. (Lebanon was the violent Middle East hotspot at the time). The concrete strong room had had its heavy iron door prized open – the concrete spalling in the heat. Small safes sat looted and with bullet holes. We were told they were shot at by the police. Anyway we got a greatly increased project out of it.

The pictures that follow are from the late 1980's and show Mdantsane's town centre. Nearby the Post Office were shops and a shebeen (drinking hall). I include these to show the context as to what followed. It is impossible to try to analyse this in political terms and I will not try, but at least they record the setting in time.

Mdantsane Post Office prior to the troubles. The "forecourt" is bustling with activity. Street stalls of vegetables and other necessities.

A large colourful mosaic by Elaine Savage depicts local life.

It is worth considering the context of life here. The bus company was run by the Ciskei government and carried residents between jobs in East London and other surrounding areas and Mdantsane. A massive mini-bus industry flourished here as well and those who did not catch them trekked accross to the railway station some distance away.

Look to the side and you see an array of other stalls waiting to tempt customers coming off the busses. Here we see blanket, even mattresses and a be frame. This is commerce at its rawest. Such markets also existed within East London, such as in Buffalo Street, but that was more curtailed by officialdom. Those with jobs coming into contact with those hoping for a sale of some kind. Goods and food bought wholesale or second hand or from the "black market" and resold with minimal profit.

At this time Mdantsane had a population of about 500 000, about the same as East London (including other races) and it stretched off across the hills, rows and rows of almost identical small houses.

Between the town centre and Post Office was some open space and someone has taken the opportunity to grow mielies (maize).

Life was tough. The independence of Ciskei brought no real benefits to the average resident and in some ways entrenched apartheid under another regime.

Bisho on the other hand had some impressive developments. We did not manage to get some of that architectural work, but did go there for work related meetings. It had a stadium, new hotels, an airport...

But it was also a different world to the life of the common man and woman and one night every single government related building in Mdantsane was torched as well as factories in nearby Fort Jackson industrial area and some properties of envied Mdantsane better off residents. It looked like a war zone.

The following picture are of the Mdantsane Post Office, the very one that we had been asked to renovate due to minor bomb damage. Now it was almost, not quite, destroyed.

My father doing a preliminary site assessment accompanied by a government representative.

This side appeared almost unscarred - except for a burnt out car.

Besides doing government workshops we did some private houses for professional black people. They still needed to live apart within allocated areas in Mdantsane. One of our clients was a doctor. We visited that of a family who owned a chemist chain (amongst others) This was in fact very impressive and we even held a fund raising event there for our childrens Montesorri pre-school. (Apartheid was at that time showing signs of fading).

On one occassion while travelling to a job in Ciskei I was nearly pushed off the main road by an 8 car motorcade carrying presumptious and arrogant government ministers going at high speed with hooters blaring.

On another I could see in the distance what appeared to be a car that had slid off the dust road into a culvert. I sped up in order to help. But it was a Ciskei cop and he flagged me down and fined me for speeding. There was also an occassion when I was fined for not stopping at a T-junction between 2 dust roads. The black cop filled out his form meticulously and asked me to state my race. I answered Caucasion. That completely flumaxed him.

When surveying the sate of old British fort sites from the Frontier Wars periodfor the SA Monuments Council. Most were in fact now within the Ciskei although the SA Monuments Council and the fledgling Ciskei cultural departments had a working arrangement. DW and I came across one very near to a rural Ciskei police station. The police got suspicious and apprehended us. Fortunately my friend spoke fluent Xhosa and managed to satisfy them.

Later architectural projects include the East London City hall restorations and work on the '70s magistrates court building.

The City Hall

The City Council had begun to modernise the city hall using in house architects. A councillor had recognised the follow of the methods and contacted us – my father because of his National Monuments involvement and me because of my conservation knowledge. We advised a specialist architect and full proper restoration with minimal change to suit changing needs and sustainability. I was then employed as site architect under that specialist, John Rennie. This subject arises here in its political context. The building had been erected in 1896 to inspire colonial pride. Now we were entering an era of socio-political change.

The only issue was that one hot day some of the plumbing was stolen during lunch break from the pond in the front right on the bustling Oxford Street.

I sat on a gable and witnessed a vast march down Oxford Street led by the likes of Bishop Tutu. Marshals in fake army gear and some carrying fake weapons; a few made from plumbing. There is more about that below.

The project had been funded by central government. One of the last to be so funded as it already saw the change of regime coming. What would a new society think of this expense on such a building?

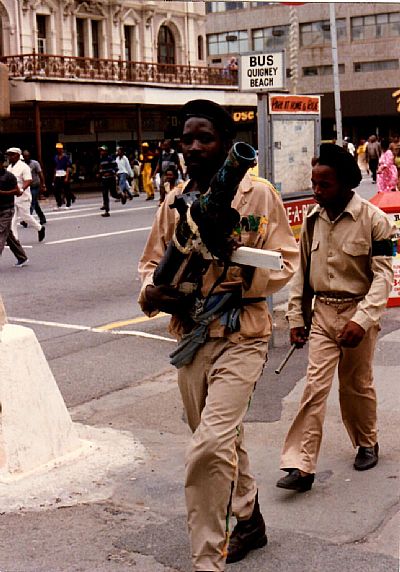

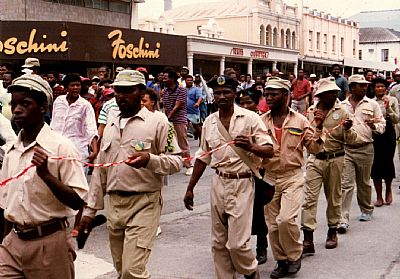

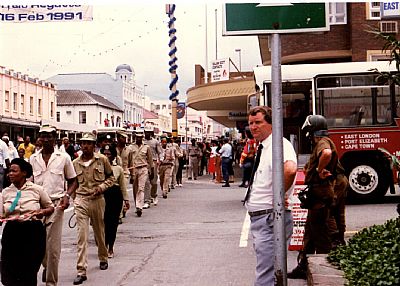

A freedom march

This would have been just one of many "freedom marches" / protest marches around the country, but it was one that I witnessed first hand in East London. It was also the first I had seen and possibly the first many others had too. There was some apprehension in the air.

We were completing the restoration of the City Hall at the time, 1991, so I clambered onto the main gable with my camera and watched from above.

.

In the lead were people such as Desmond Tutu and Nancy Charton. (I had met Nancy through the SAIRR. She was not first female ordained priest in the Anglian Church of South Africa, but someone who spoke up about the politics of the day, mainly through the Black Sash).

,

Heading up Oxford Street

The forefront of the march returning down the street. I didn't recognise anyone now, the key figures by this time having left the march.

Why should I feel apprehensive? Wasn't this leading to a free society that I had always envisaged? So I climbed off my lofty perch and went down to the street. By this time the march had moved quite far up Oxford Street and was now heading back to their starting point. Khaki clad marshals kept everything running smoothly.

Remember that this was still before the abolition of apartheid. The mood was mixed. Some jubilation in party mod. Some a little recalcitrant. Some that looked as if they felt they were on the cusp of something better. And us whiteys somewhat still nervous. But it was overall positive.

Coming past the Main Post Office.

Amongst the "armed resistance" were some marchers carrying some terrifying weapons. But not to worry, these were replicas made from drainpipes and sticky tape etc

By this time the marshals were getting a little weary.

Note the single armed white soldier to the right.

And bringing up the rear, some SA military and police vehicles. Just in case.

Apartheid evaporates

Apartheid did not just happen overnight. There was a lot going on behind the scenes. IDASA had been created, This could cross party boundaries and even international ones too. The Institute for Democratic Alternatives in South Africa (IDASA) later known as the Institute for Democracy in South Africa was a South African-based think-tank organisation that was formed in 1986 by Frederik can Zyl Slabbert and Alex Boraine (both of whom I had met through the Progressive Party). Its initial focus from 1987 was creating an environment for white South Africans to talk to the banned liberation movement in-exile, the African National Congress (ANC) prior to its unbanning in 1990 by the President F. W. de Klerk. After the South African election in 1994, its focus was on ensuing the establishment of democratic institutions in the country, political transparency and good governance. [Wiki]. We attended some of its events. And also some initiatives of other organisations. Amongst the latter was a forum arranged by the wide of the dominee, who we knew. It was for women, but men could attend. I was told that the dominee would be there, but I ended up bing the only (conspicuous) man amongst 200 Afrikaner vroemense.

Nelson Mandela' is freed and the healing begins

I made sure that my eldest daughter watched Mandela walk to freedom on tv. She was just old enough to remember it. Apartheid fell and Mandela took power. We watched the long queues at elections and then his inauguration on TV.

This is how we watched - live - as Mandela walked free. A long wait staring at the TV. A momentous event captured by camera of our TV screen.

Then the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up. It met in the City Hall when it was held locally. It appears that it took on a new aura amongst the previously excluded. It was to host many an event of other races or without the context of race at all. But if the project had stalled or been planned too late, this may never have happened. The two cannon used to quell the Basutoland Uprising and had stood outside for generations quietly never replaced. The mounted soldier of the war memorial still stands proudly in front. A statue of Steve Biko has since been added to below the clock tower. I waited in the crowd to see Mandela arrive to address them (although business called and I missed the actual event, I did get a fleeting view of him). See below.

The Magistrates Courts

The magistrates courts had been designed in the '70s at the height of apartheid by George Albert. Now as apartheid ended much need to be undone. We were commissioned. Each of the courts of white magistrates (no jury) was symmetrical. The public came in at different sides from different corridors depending on race. The accused were usually held in cells in the basement segregated by gender and race. An underground tunnel led through to the police station. Main entrances from the street were also separate. Other public facilities such as pensions were not quite as vehemently separate, but still so signed. I was project architect. An interesting experience. Roof flashing, a judge's wallet and other items stolen during the works. We programmed the works so that most activities continued to operate so this all happened with public, adminsitrative officials and even magistrates and judges were in the building. (Judges were on a travelling circuit system and only used this court on this basis). I was to use the courts only twice myself. Once to try to reclaim unpaid architects fees. And to be a witness when we had been robbed at home and the culprit caught.

When I wrote my book, The Urban Trail, I was very conscious of its white orientation in terms of architects, property owners, examples of authority, industry and anecdotes. When I rewrote it I aimed to rectify that. Unfortunately it remains in rough draft on stiffy disks as we then emigrated. I kept that old pc that could read stiffies for some years, but it is difficult to set it up here in the UK and I dumped it. A full print out of the draft is amongst my books although it does not have illustrations. That draft though is recognition of the many craftsmen of other colours and of the sheer muscle-power of labour that went into creating the architecture and form of East London. And it covers all of greater East London too. While it does not aim to be a history book nor one about politics as such it does include key events including those of arson and violence. It was very startling to record all such events in just the East London and surrounding areas during my lifetime. [The Urban Trail - a walk through East London's Central business District and older suburbs. 1989. Still available on 2nd hand book websites].

It is now well over 20 years since we emigrated to Scotland (1999). So many of our friends have done likewise. Between us we have personally known 20 people who have been murdered over many years. We less in touch these days so These are not apartheid related, well not directly. My parents maid by a woman jealous of her liaison with her man. The man who played the keyboard at our parents wedding. The man who took our photos at ours. A university friend shot on the doorstep of his Wild Coast holiday cottage one New Year. Politics may be the cause in some ways. Or the solution. But the causes are social and economic. How do you resolve all that?

Just in those 18 years of marriage, building a house and having two daughters, we got robbed on average about once a year. Car radios. Hose pipes. Clothes from the washline. My car was taken from the garage one night (it still didn't have garage doors yet). They managed to hot-wire it, but could not release the steering column and didn't get far. A neighbour was woken by his dog and went after them with a revolver. We were woken with loud knocking on the door by the police. And break-ins. Although I had fixed down the windows with restrictors, they managed to break the glass and twist the wooden frames. Each time I added more. One Sunday morning after some great time on the beach we returned to find the kitchen door open. A great deal had been taken down to the river, close to the bottom of the garden. Bedding, tv etc. While we awaited the police, a young guy wandered in, apparently not realising that we were back. He fled into the bush and I gave chase in my flip-flop sandals but was soon asthmatic. The police arrived and looked around. But the dog squad had arrived from a different direction and scoured to bush. He saw them and kept quiet. He, then thinking they had gone off raised his head. And they had him. A very young meek looking guy and very likely working with others who had disappeared. While he was interrogated in the garden I fetched the hoard from the river bank. My paddle ski had been taken as a means of getting it across the shallow water. I then joined the police and the family talking to the thief. We noticed that he was wearing my wife's watch. Some jewellery and my watch given to me by her were never recovered. I attended the trial accompanied by a daughter in one of the courtrooms I had recently helped renovate and remove all signs of apartheid from.

The Code Blue security sign on our garage. (The bars over the outdoor light were to protect it against netballs being played by the kids. The ring was just above it).

One morning I had just started work in our office in Devereux Avenue, when I got an urgent call from Ines. Please come immediately. I rushed back. We had recently extended the house. She had been lying in bed reading the Daily Dispatch which would have been flung down the front path. Someone had walked into the room. Fortunately he was greatly surprised to find someone still there at that time of day and he fled. But he returned to “negotiate” with her. But as the room was new the keys were still in the locks. She jumped up and just in time was able to lock the door from the inside. By this time our maid, Sylvia had arrived for her day's work. And as he rushed past her she screamed at him. We were indebted to her arriving just then. We never caught that intruder.

What we did do was to immediately get panic alarms installed around the house. 5 in all with press buttons in easily accessible, but not obvious places such as behind curtains. All this was transferred by wireless signal to CODE BLUE armed security who had a presence in the suburb and claimed a 10 minute response. Not sure how effective that timing would be, but way better than a police response. And with fewer scruples about using their arms. We felt a bit better although constantly nervous about setting it off accidentality.

We felt less specificaly victimised when we saw this. The small quayside in the harbour had a police station which provided both security and border services to visiting foreign yachts. But it was itself subject to abuse and had this "secure" palisading added tightly around it. And it had its own personal private security company on hand too - just in case. Notice the RED ALERT response sign on the doorpost.

This whole episode scared us. For years my wife had asked to take the family to move to Scotland, her country of origin. I, though with the business, love of wildlife, the beach, paddle skiing etc resisted. But now it was me that insisted on emigrating. And we are all now completely settled and integrated here. At this point our parents moved into this house and my brother moved into the Selborne house.

Car Gaurds

This was another side of security in many cities including East London. No I haven't spelt that wrong. They did. Let me explain.

Car break-ins were and are a regular problem, even in broad daylight. The main objectives were car radios, which used to be removable. Recruiting from amongst those who were probably the miscreants, car guards were given means of identity to wear and cards to carry. This misprint occurred and remained for years. These guys would roam the streets and carparks and ensure that your car was safe with the expectation of a fee on your return.

The Republic of Ciskei

As noted above, we did some work for the Ciskei Government, well incoming government, as it was still very much under Pretoria management. But that led to us getting invitations to the inauguration of Lennox Sebe as the new president and to the independence celebrations that went with it and it is worth giving it some separate discussion here. Ciskei had been defined as a self-ruling homeland in 1961, but had to wait until 1981 until it actually attained true independence status.

The motorcade arrives in front of the podium. Press photographers (and who knows who else) crowd the car. Wally and I were sitting a few rows up amongst the invited guests.

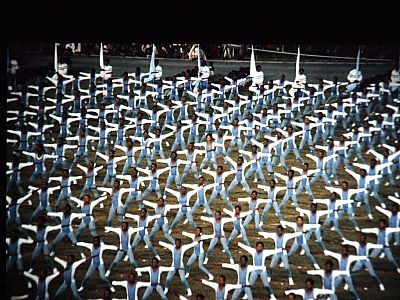

A fine gymnastic display in the new national Ciskein colours.

I cannot remember who the South African officiating was, but here he is resplendent in his gold chain.

The new president receives his ceremonial chain.

So far. So good. There was much marching about and military band music. But then.....

Oops. The Ciskein soldier tugged at the flag rope. It had stuck. So he tugged some more. So he tugged a little harder. The whole flagpole crashed over and broke in two.

To many of us watching, this was symbolic. An omen.

A bunch of soldiers rush over to help. You may notice that these are in khaki, SA soldiers, not the blue grey of the Ciskei regiment.

So here you have it. South African flag had come down for the last time and the Ciskei flag was flying proudly for the first time. Symbolic? A fledgling "independent" state still propped up by South Africa.

It was really nice to see the City Hall being accepted and used by the various races. We had begun its restoration and alterations while the first cracks in apartheid were showing. The budget had been set under the white city council and supplemented by a granted from central government. It stood there in its reddish hues reinstated from samples of its original oxide plaster yet was largely inspired by the Victorian architecture of England, even with a clock tower that my paternal grandmother used to say was like a small Big Ben.

In its forecourt were a pair of fishponds/planters of rough stone designed by my fathere while with the Council. These were removed to created a more formal approach, but retained right in the centre was the imposing Boer War horse and rider on a plinth complete with the names of the fallen.

Canon from the Basuto uprising flanked the main door, but these were quietly sent off.

I had witnessed the freedom marches from the City Hall roof while participating in its restoration and briefly saw one of the Peace and Reconciliation sessions within.

As mentioned above, a statue of Steve Biko was unveiled in 1997 below the tower. Unfortunately I was committed to a meeting I had set up about this time so could not stay, but I did see Nelson Mandela arrive to unveil it. This was a significant moment. Mandela as the new President was here to officiate in the rememberance of someone who was in many ways contrary to the ANC, yet had become a martyr. Even though he was a hero to many of other races, he was almost unknown to most of us whites. Donald Woods while editor of the Daily Dispatch had befriended him and endeavoured to give him coverage. That had led to the Cry Freedom film by David Attenborough and suddenly he had, posthumously, become more widely accepted. But since then he has receded again in the wider public consciousness. Monuments help to rectify that.

Stephen Bantu Biko was an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. A student leader, he later founded the Black Consciousness Movement which would empower and mobilize much of the urban black population. Since his death in police custody, he has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement. While living, his writings and activism attempted to empower black people, and he was famous for his slogan “black is beautiful”, which he described as meaning: “man, you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being”. [Arts and Culture Google].

Sometimes we watch history. As a white South African I feel that I have hardly been within that history, at least not in the sense that I have really participated in it. Sometimes we almost touch it. I have seen Mandela at a distance. And de Klerk. As for Biko, I once answered the office phone and on the other end was Biko's sister. (We had employed some staff of other colours and one was doing a small private job for a community project that involved her).

Politics, memory and symbolism are funny things. Unfortunately I do not have a proper photo of the statue anymore. It was erected much too early before the ceremony. Local hero Steve Biko remained on his pedestal for ages bound and gagged.

I was amongst the crowd waiting and waiting for things to get going. Mandela is there somewhere. The closest I ever got to him.

Here you clearly see the Boer War memorial, for this occassion somewhat ironically decked out with a black union or political banner.

(In an earlier era, I may have even have been invited onto that podium. I actually did experience that once, but cannot even remember why. Just the bygone privileges of being white at that time).

With the end of apartheid everyone in the Ciskei lost their Ciskei citizenship and it reverted to that of South Africa. The transition was reasonably smooth. Some town and province names changed and so too did some of the administrative boundaries and systems. When we redid the East London City Hall we set up a new council chamber to absorb an increase in councillors. But that was not to be. The ill-named Border district with historic references to the 19th century Frontier Wars was dropped and it was absorbed into a redefined Eastern Cape Province. In 2000, East London became part of Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality, also consisting of King William's Town, Bhisho and Mdantsane and is the seat of the Metro. [Wiki]. I was invited to sit on an interim panel known as the Provincial Arts and Culture Task Group (PACTAG), representing the Border Kei Institute of Architects. This was a short lived group, but smoothed the transition from regional council and city council to the new regional administration.

Security, a booming business

Several security firms have sprung up over the years, some local, others branches of national companies. Very often such firms are begun by ex-policemen. The one that we used in Beacon Bay (as shown elsewhere) was Code Blue. Other well known ones are Red Alert and Hartwig and Henderson 24 hour response.While the demise of apartheid should not be seen as a direct cause of an increase in security risks, the failure to ensure sufficient jobs across the racial spectrum coupled with the increase of informal almost undeterred, settlement ever closer to those with better incomes and property, naturally led to easier pickings for those so determined.

The police force has long been open to all races. While this helps enormously in some ways, such as language, etc, it also means great nervousness witharrests. And so private security firms seem to be more effective than the police. They very often get to a crime scene ahead of the police. And while they abide by the same rules about arrest and shooting, in practice they seem less inhibited.

A family home guarded by Hartwig and Henderson 24 hour response.

Update 2025

We keep up to date with SA events. As I write this in 2025, the following has appeared in the Daily Dispatch :

Anxious residents have accused Beacon Bay police of shutting up shop at night and leaving them without assistance during peak crime time.

Officers are operating from a shipping container in the parking bay outside their premises, which was condemned for safety reasons on May 6.

No one appears to know how long the situation is expected to last.

The station, employing 43 officers, serves Beacon Bay, Nompumelelo and Ducats.

But residents say their calls go unanswered and they have to rely on neighbourhood patrols and crime forums to get help.

ARTS AND CULTURE GOOGLE website on Biko : https://artsandculture.google.com/story/steve-biko-the-black-%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20consciousness-movement-steve-biko-foundation/GQWBgt1iWh4A8A?hl=en

JUSTICE website : https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1997/9709/s970912b.htm

WIKIPEDIA - SHARPVILLE MASSACRE : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharpeville_massacre

BISHO MASSACRE : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bisho_massacre