DUNCAN VILLAGE

Also see POLITICS & SECURITY for a discussion on a meeting I was involved with through the SAIRR to assist in resisting the removal of black people from Duncan Village.

This may seem an odd subject to have in this website on my greater family stories. We have nothing really to do with it, but I visited several times for work and while representing the South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR). It had a profound affect on my perceptions of racial separation, lifestyle differences and our own comparative privilege as whites during the implementation of apartheid.

These photos were taken at about the same time that I was involved through the SAIRR in trying to prevent the ousting of black folk (to Mdantsane) to make way for coloured folk who were a step higher up the social scale by apartheid definition. This was in the early 1980s.

We were shown around by local residents and got to see inside some very crude shacks. What was striking was the contrast within : very little, yet absolutely neat and tidy. Floors would be earth overlaid with lino. Walls "wallpapered" with the misprinted and unused cardboard from local factories. A popular one was that of smarty boxes.

Those in the more established older areas were more substantial with small fenced yards. There were kids running around, but there were always some adults keeping an eye on them. Everyone seemed to know each other and they would be sharing the latest gossip over the fence. It was commented on that white kids didn't play together in the street like theirs. (Actually we had when younger, but that was fading, mainly out of safety concerns).

Any neatness was kept within. Outside there was a mix of conditions and that was mainly dire. Competition for space for the "informal housing" led to crowded conditions and we even visited huts built over graves, mainly black people living over the graves of forgotten coloured people.

The implementation of apartheid led to the separation of races into districts and with the Republic of Ciskei about to achieve independence, this included the creation of the sprawling "town" of Mdantsane by the South African government specifically for black people.

Coloured folk had the better areas such as Buffalo Flats. The Indians, so many of whom were successful traders, had a more discreet area to the north of the city centre. We whites had everything else.

As the black folk were cajoled out of Duncan Village, the happy mix showed tensions. With housing in short supply, some coloureds started to eye the properties of black people.

As around the world in every culture, urban renewal eventually becomes a necessity. Add in the pressures of class and income differences and it takes on a momentum of its own. Add in the powers of apartheid and it can become brutal.

The very need for urban renewal derives from the decay and unsuitability of existing urban fabric. The trouble is that once an area is earmarked for renewal, it decays even more and faster as residents no longer want to put time, money and effort into its upkeep. That in turn gives the authorities the excuse to take ever more drastic action.

What you see below is a microcosm in place and time. A great deal, but not all, was absolutely dire. Yet look at the smiles on the childrens' faces. Expectations and making do with what they had enabled them to get through life. Unsurprisingly there was the other side to this. Many kids formed little gangs and lived off their wits roaming the city centre or privileged white suburbs. They would sleep rough using flattened cardboard as beds in alleys and disused buildings. Glue sniffing, amongst others, became a pasttime even for very young kids.

All over the country "informal settlements", squatter camps were springing up as rural folk drifted to the cities and towns and those already living in the "locations" wanted to be closer to work and opportunities. The authorities struggled to formalise them with services and housing. Duncan Village, by contrast, was being dismantled. Its residents sent off into the sprawling township of Mdantsane beyond the city limits. That urban sprawl would reach about half a million; about the same as East London itself. You can see the concern about the numbers. "Swart Gevaar" fears - black danger. Apartheid moved the problem away rather than resolved it. During these years, few could grasp a society without racial equality. And the residents of Duncan Village were to suffer for this, even if they had been here for generations.

Also see POLITICS & SECURITY

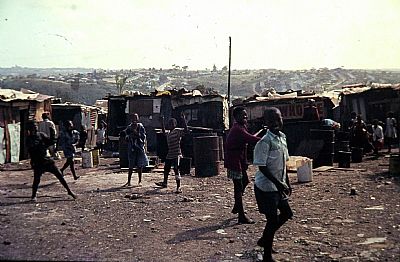

Informal shacks and gravel that could turn to mud in an instant. A lone power pole. In the distance are the better houses of Buffalo Flats for coloureds. Smiling kids play for the camera.

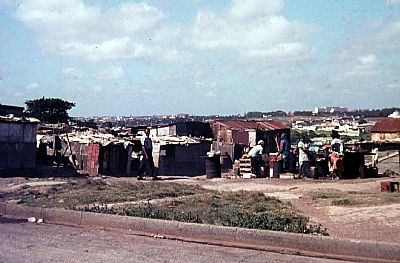

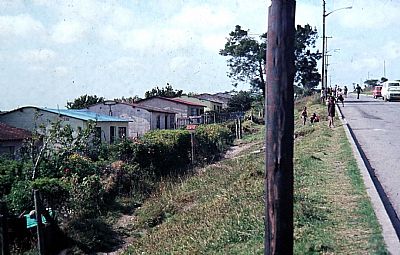

A similar scene, but here the houses are properly built and there is even a street light.

Corrugated iron was a popular choice for housing across the social spectrum. Cheap. Quick to erect. But difficult to insulate. Here we see some that show an earlier era of establishment - with some ramshackle extensions. The street here is tarred, although the area inaccurately still called a "pavement" is gravel and weed.

Women do their daily chores in shared clusters of fire enclosures amidst informal shacks. Note the low roof levels of many as defined by the standard size of corrugated iron sheet. In the distance is East London's industrial area.

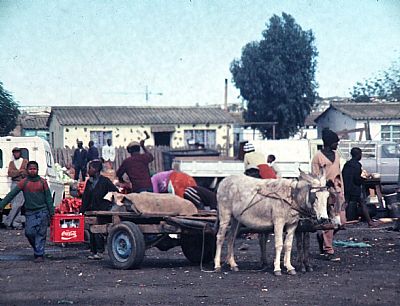

Here we see properly built houses as provided by the authorities. A two-donkey trailer made with a discarded truck axle and wheels delivers supplies. Two young men carry a heavy Coca Cola crate which appears to have milk in it. You can see stalls between the vehicles. One is the butcher and you can see the red raw meat with the butcher himself wielding an axe. (Similar scenes were to be found within Mdantsane, even at the gates of the large Cecelia Makiwane Hospital).

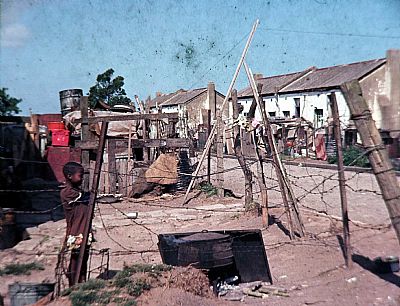

The properly built houses would be added to, as seen across the road. On this side we see a ramshackle yard enclosure with a large iron pot over an open fire screen against the wind. Such pots had become ubiquitous across Africa. Most were made in the Carron works in Scotland. They were often given the derogartory name of kaffir pot, but their Afrikaans name is better :drie pooitjie potjie. (Three legged pot).

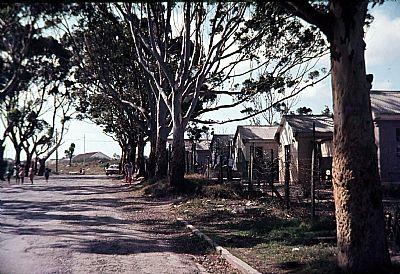

A tree-lined road and established houses tell of a better time.

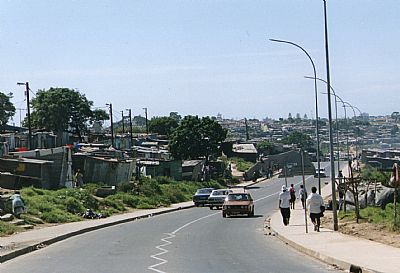

The main road through.

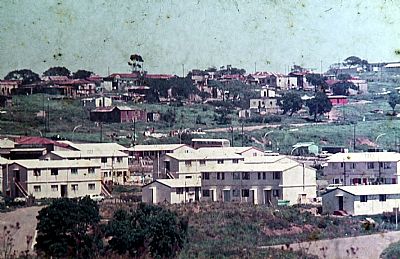

Some of the better, newer housing.

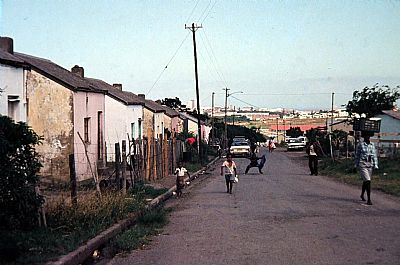

A reasonable street scene.

This row of small houses was always neat and well looked after. It was in one of these that I met Mabel Mdaka, a nurse who advised us on the meeting we at the SAIRR helped arrange to resist the removal of black people. These houses were tiny inside, but we were welcomed with tea and biscuits around a small coffee table.