Wealth and/or Empire

The flag of the Scottish Guinea Company

Christopher Smout once calculated that about 200,000 Scots still migrated to the Continent in the early part of the seventeenth century. Between thirty and forty thousand of these went to Poland but there was also a growing Scottish presence in France, Sweden, Denmark and the Low Countries according to Ned C Landsman.

With these well-established routes to possible success available to them people were inevitably going to be reluctant to consider the dangers of trans-Atlantic travel and strange lands.

With the undoubted benefits of hindsight we can also see how the lack of proper research and planning contributed to the failure of the early Scots trans-oceanic settlements. Bitter lessons had to be learned and more independence to be lost in the process. Empire building required resources both financial and human that the Scots did not have at the time. However Scots learned their lessons well and, via the new concept of Great Britain, became leaders in the drive towards a British Empire.

Early "Plantations"

There certainly seems to have been a seismic change in attitudes at this time. New lands, fresh raw materials to be exploited including gold and silver, new attitudes about money all combined to offer far more people the chance to become wealthy lairds in their own "dominion" or on a much greater tract of land abroad. There were precedents to follow. Virginia and Ulster had been “planted” in 1606, Newfoundland in 1610, Bermuda in 1611. Why not specifically Scottish settlements abroad?

The Scottish monarch, James VI, who had become the first Stuart King of the United Kingdoms, had raised hopes amongst some Catholics of toleration. They were to be sorely disappointed. He found that the English treasury was chronically deficient. He was hemmed in by powerful Protestant courtiers. Perhaps because of the precariousness of his constantly threatened childhood, he was a firm believer in the demonic powers of witchcraft and may have been encouraged to associate these with papacy. The attempt to blow up Parliament was not best designed to erase that fear.

Whatever his personal fears and restrictions were he certainly chose to back the planting of Scots and English to quell Catholic rebellion in the northen counties of Ireland.

The Ulster Baronets

One aspect of this deliberate imposition, which was designed also to satisfy some of the hunger of the Treasury, was the creation of an order of Ulster Baronets. Allowed to call themselves “Sir” they were still not admitted to the closed community of “the aristocracy” but were nevertheless placed above “knights” in order of precedence.

Knowing your place in a hierarchy of importance runs deep in British consciousness of law, order, and social value. It became a distinctive facet of early imperialism.

If English (not Gaelic) was your first language, you were Protestant and claimed loyalty to the King you could pay £1,095 for your raised foothold on the social ladder and also own a tract of confiscated land in Ulster though you also had to promise to maintain a company of 30 soldiers there for the King as well.

These rules were not always upheld rigidly because the Treasury was desperate for money and there were simply not enough takers who were interested. Most of those who took up the offer, however, came from northern England and southern Scotland not, as far as I know, from hereabouts.

Another aspect of this “planting” was to recur in other schemes. This was the conviction that it would quickly become obvious how "superior and sane" English Protestantism and “Civilisation” was so that Catholic “superstition” and Irish “barbarity” would just naturally fade away.

The importance to people of their inherited beliefs and practices and of their ethnic identity was simply ignored to everyone’s lasting cost.

Those who did not comply with this preconception were considered stupid, backward or dangerously subversive. It is perhaps only with post-colonial insight that we can see how destructive this attitude can be and how much lasting conflict and suffering human presumptions of “superior rightness” can cause.

Nova Scotia

The flag of Nova Scotia was only created in 1858 though the colony was founded in 1625

Sir William Alexander of Menstrie persuaded King James that Ulster could offer a model for creating another outlet for Scottish pride. This had been dented rather than increased by the transfer of their king and his court to London. A “New Scotland” could sit well beside a New England (planted in 1620) in the Canadian Maritimes.

New Baronets of Nova Scotia were thus created by Charles I. They needed £2,000 now to buy that privilege, though, which was quite a leap from the price in Ulster.

Uptake was, understandably, very reluctant at first but in 1629 Menstrie’s son was able to set out across the North Atlantic with some would-be settlers.

What they had omitted to calculate was just how weak the British hold on this area was compared to the existing French and Mi’kmaq population.

They were forced to abandon their plans just three years later when the land they had claimed reverted, by the Treaty of Paris, to their former colonists, the French.

Most of the new Scottish baronets never saw their land and gained no revenue from it. Menstrie, himself, was nearly bankrupted by the venture.

However, this brief three-year stay left an indelible ethnic memory and a lot of colourful heraldry.

When the British did eventually dominate in Canada this area became an easy focus for asserting Scottish/ Canadian identity by its very name.

The Guinea Company

Gold and slaves attracted some London merchants to invest in a joint stock trading company to the coast of what is today Ghana in 1618. Under the leadership of Nicholas Crisp it eventually became highly profitable. As a royalist, Crisp eventually fell foul of the Parliamentary establishment and the Company was dissolved.

A Scottish Guinea Company was chartered by Charles I in the 1630s but only made one expedition in 1659 with two ships one which returned safely with a 50% profit on its cargo. The other, after having remained to trade with considerable profit, was seized by the Portuguese on its return journey and the crew killed.

The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies was created in 1695 by Act of the Scottish Parliament and dissolved along with the Scottish Parliament in 1707. This was the Company that attracted so much Scottish capital investment and hope for the Darien venture. The name of the company now made its trans-Atlantic ambitions plain.

“The Atlantic Triangle”

What was, indeed, most lasting about this venture was the fact that Scots had declared a vested interest in the trading circuit that became known as the Atlantic Triangle.

The simplest diagram of the Atlantic triangular trade pattern created by Simon P and modified by John Monnpoly. Wikipedia

The Darien proposal was very much a part of this envisaged trading ambition.

The Darien Scheme

Portrait of William Paterson in John H. Innes: New Amsterdam and its People 1902

William Paterson, originally came from Dumfriesshire but having spent time in Bermuda he proposed a Scottish settlement on the isthmus of Panama. He was to be sadly mistaken about its possibilities and so were most of Scotland’s leading citizens who invested in the proposal.

There is an ever-growing literature discussing the pros and cons of this venture and who was responsible for nearly bankrupting Scotland in the process.

There is still, also, deep resentment in some people at the chosen “cure” by uniting the parliaments of Scotland and England in 1707.

Robert Burns is often quoted as calling those who promoted the union “Sic a parcel o’ rogues in a nation”. It is not often remembered that he was, in business life rather than in his literary capacity, willing to accept a job on his friend’s British Jamaican sugar estate which, of course was profitable because it depended on African slave labour. Burns was a pragmatist and a skilled satirist so, sometimes, ambivalent in what he says as well as memorable.

These initial nationalistic project failures were by no means the end of Scotland’s share in imperial expansion. Scots ambitions and drive have proved to be highly resilient.

Scots "Empowered"

Westminster itself soon found it was being led by Scotsmen.

There have, so far, been 12 Prime Ministers since the union who were “made in Scotland” and goodness knows how many Chancellors, Foreign Ministers etc.

Henry Dundas became so powerful without being Prime Minister as to qualify as W.S. Gilbert’s “The Lord High Everything Else” in The Mikado. His contemporaries nicknamed him “King Harry the Ninth”.

Military and Naval leadership has always been heavily weighted with Scots and military careers have usually been regarded honourably in all ranks.

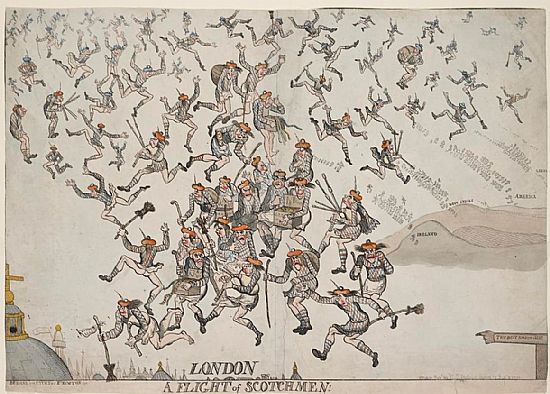

Satire: Scotsmen 'raining' onto London, Ireland, West Indies, America and Germany, all wearing tartan and berets, some with bagpipes; with signpost bottom r. 3 September 1796 Hand-coloured etching

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Scottish merchants seemed to fall on London like a plague of locusts after the union according to one cartoonist. Their greater flexibility of operation, kinship solidarity, competitive spirit and drive were quickly felt not just in London but round the world.

The Scots may not have made their mark as a conquering nation. That is something that they can, indeed, be thankful for. As individuals and in small group enterprises from Governor Generals to clerks they were highly effective in creating the British Empire and colouring it with a distinct heather-pink tinge.

The stories of some of those individuals and groups form the main body of the mini-biographies which follow.