Alexander Grant 1705-1772

Sir Alexander Grant of Dalvey

No known portrait of this subject has been found which, in itself, is a mystery since he became a very public figure.

Inverlaidnan

Alexander was an Inverlaidnan Grant by birth. His mother was a Mackintosh. Both his parents were loyal Jacobites.

OS 6” map showing Inverlaidnan and the Sluggan Bridge. Extract: Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

Photo of the Sluggan Bridge which carried General Wade’s "military road" that allowed his troops to "police" the "rebellious" Highlands over the sometimes turbulent River Dulnain. All roads were single track and unmetalled of course at this time. It is menacingly close to the Jacobite stronghold of the Inverlaidnan Grants. Photo: Courtesy of The Historic Highland Environment Board

Dalvey

In 1701, soon after inheriting Inverlaidnan, Kinveachy and Lethendry, Alexander’s father, Patrick Grant, purchased the farm town of Dalvey from his brother-in-law, Sueton Grant, who moved to the smaller property nearby of Aird of Dalvey. It was probably, therefore, at Dalvey that Alexander was born 1st of July 1705.

Wintery view looking back towards Dalvey farm and the Cromdale ridge from Aird of Dalvey. Photo courtesy of the Aird of Dalvey website.

His birth came at a time of intense competition for Crown allegiance and for property, status and power among the Scottish lairds as well as between the Parliaments of Edinburgh and London. The union of the Parliaments took place, not without rancour, just two years after the birth of Alexander. Subsequently, Scots interested in seizing the new opportunities for government and trade, began to move to London for a good part of the year and those who did so also tended to support the Hanoverian monarchy. The Grant clan chief was already moving in that direction and would definitely refuse to “come out” in the ’45. This would further increase tensions within this part of the country.

Alexander’s Grant families had been increasing their own power base for some time by the use of wadsets - monetary loans to the chief in return for security of tenure in a property for long periods which allowed them to develop the land and recoup good rents from their subtenants for themselves.

This also granted them the status of baillies in order to administer justice legally, in tandem with the chief, in their temporary mini-realm. An interesting PhD thesis by Charles Fletcher called “Justice and Society in Strathspey:The Regality Court of Grant c1690-1748” presented in 2020 at Edinburgh University deals precisely with this whole topic of changes in power-sharing and has some detailed information about Inverlaidnan.

In 1711 another ambitious relative, John Grant of Dalrachney, took a nineteen year tack of Inverlaidnan that was extended in the following year to a virtual lifetime of fifty seven years.

As part of the contract, he agreed to build a stone house for the first time on the property. Until then, like most tacksmen, he had simply lived in a rather more grand version of the turf-covered cruk-house amongst his subtenants in a farm-town like the one reconstructed in the Highland Open Air Museum.

Photo of a reconstructed farmtown settlement : Courtesy of the Highland Folk Museum

Dalvey, where Alexander was born, may not have had a stone farmhouse either at the time. They were to become a distinctive feature of the age of “improvement”.

As chiefs became increasingly metropolitan in outlook the cracks widened in the older social structure. The “lairdly” chief now sought to live apart and above his subjects like, though not fully accepted as, British "aristocrats".

University

By 1722 the Dalvey estate had reverted to the ownership of the laird of Grant though Patrick, himself, lived on to be 101.

His son, Alexander, followed a basic course of pharmacy at Aberdeen University when he was about fifteen though no account, so far, of any graduation has been found. With this he was, however, able to claim to be a medical doctor and head off as a seventeen year old in the hope of making his fortune in the enticing sugar bowl of Jamaica.

Jamaica

Alexander was able to join two cousins already established on their plantations.

Professor Hancock identifies these cousins as Edward and David Grant who had acquired lots in St Elizabeth and Westmorland a couple of years before Alexander’s arrival. They were all joined a few years later by a Daniel Grant.

Although Edward was the middle name of the Bonnie Prince there is not a single Edward Grant on the Scotland’s People website identified at this time. There are numerous Edward Grants after this time in Jamaica though!

David and Daniel are occasional family names in the Glenbeg/Lethendry and Ballindalloch families though there is nothing found so far to offer a precise identification. A last will and testament written by a merchant called David Grant with a wife called Ann was written in Great Queen Street, London and presented for probate 4 December 1792 though I think the date of writing reads “one thousand seven hundred and seventy nine”.

Great Queen Street, London where David Grant may well have written his will after returning to Britain.

These three Grants need much more research please from others.

With their help over the next nine years, “Dr” Alexander gradually morphed into "skilled trader" Alexander, in partnership with Peter Beckford jnr.

He also began to acquire a plantation of his own in St Catherine.

Photo of The Flat Bridge over the River Mumma in St Catherine’s parish that was built about 1724 and would have been known, therefore, to Alexander. It still carries modern traffic - with care!

In manoevering amongst the risks and spills of investment and commerce he had found his real metier. He had gone to Jamaica to make a fortune for himself and for the honour of his family not to heal the sick and he kept his focus fixed.

Such entrepreneurship was possible with little starting capital because the island economy worked largely on credit. As a result, acquiring property was relatively easy, but reselling it for actual cash was far more difficult. Most people who wished to return home left managers on their estates and lived on the yearly profits.

Absentee landlordism allowed a new middle class of managers to grow in the colony further degrading the actual labourers into means to an end - an end from which they would derive no direct benefit. The same was beginning to happen in the factories and mines back in Britain, of course, though it was not underpinned so cruelly by the gross fallacies of racialism as in the American and Caribbean colonies. In Britain the "imagined" distinctions involved a triple “class” system with the addition of vague notions about a few families “of quality” who were somewhere above a middle class but well below the aristocracy and nobility. Racialism quickly grew, however, as the empire extended and almost obliterated class in the colonies.

The much later “compensation” payments from the government for the emacipation of their slaves was probably seen as the great release of their capital “investment” that many planters longed for back in Britain. Very few saw themselves as investing in the colony for its own sake.

In 1737 Alexander married the daughter and heiress of another planter with a large holding on the St Catherine estate called Elizabeth Cooke and, together, they headed back to Britain to make a home and run a successful business in London, whilst drawing revenue from their Jamaican plantations.

Alexander attributed the continuing success of his ventures in Jamaica to his namesake cousin from Achoynanie (usually referred to now as Arndilly) whom he had appointed as his manager.

London : At the Sign of the Golden Steed

Alexander and Elizabeth lived and traded, at first, under the appropriate sign of a gilded Pegasus in Magpie Alley at the invitation of Alexander Johnston and his wife Jane Gordon.

Partnership was essential for entry into the London world of fiercely competitve, independent traders who were challenging the monopolies of the older merchant guilds. Johnston and Grant dealt mostly in pharmaceutical supplies to Jamaica and America and return cargoes of sugar, rum and hard woods.

It did not take Alexander long, however, to make the contacts and to seize the wider opportunities that London offered. He diversified both his markets and commodities when he set up his own business.

By 1753 his headquarters were established at 9, Billiter Street, and Alexander had begun building up what Hancock rightly calls “ a global merchandising empire”.

A Map of the Aldgate Ward in 1772 with Magpie Alley and Billiter Street highighted. The proximity of the Naval Office also highlighted may be a clue to Alexander’s ability to win a lucrative contract to supply the Navy based in Halifax Nova Scotia.

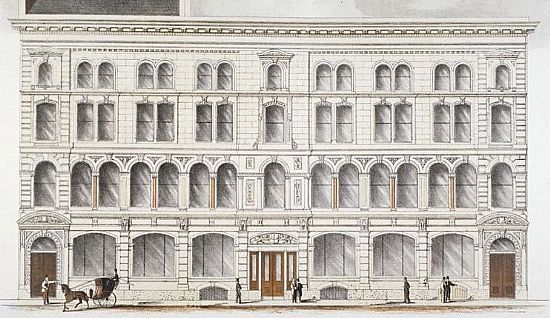

Mercantile premises on Billiter Lane/Street. This may not be an image of his precise domain and is only used as an indicator of the grand scale of Alexander's enterprises.

Mercantile premises on Billiter Lane/Street. This may not be an image of his precise domain and is only used as an indicator of the grand scale of Alexander's enterprises.

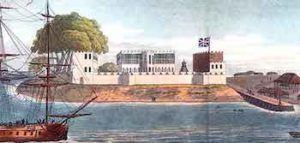

One aspect of that empire which clouds our view of Alexander’s incredible economic achievements was a project in conjunction with Richard Oswald, Augustus and John Boyd, John Mill and John Sargeant. This group took over a “slave factory” on Bance Island near the mouth of the Sierra Leone River on the West African Coast. It had been founded as early as 1670 and was only closed down in 1808.

At this base they purchased (from their African “trappers”), men, women and children who were then “stored” in the “factory” i.e. "warehouse" ready to be “traded” to the highest bidder and then “exported”. We find this complete commodification of human beings totally indefensible today but it would take another century for slave trading to become illegal and considerably longer for racial prejudice to be even challenged in Western society.

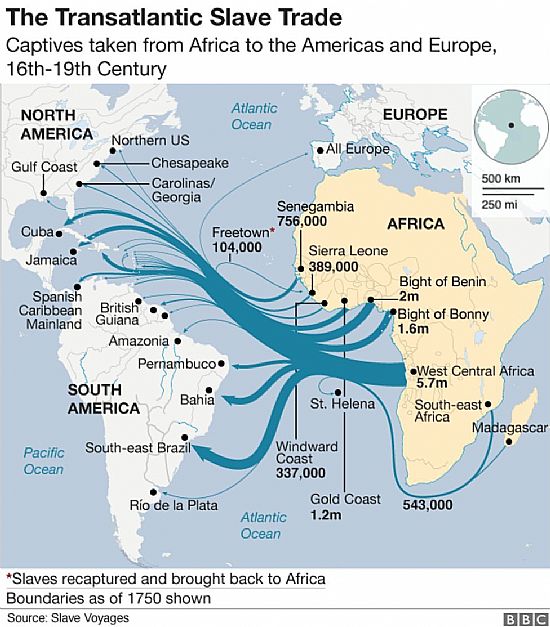

It is important when seeking to establish responsibility and blame to keep in mind the long history of slavery as part of trans-Atlantic trade. The map below attempts to show the colossal scale of that traffic over time. Bance Island was, however, responsible for a relatively small proportion of that colossal overall "commerce". Not all the trading was done by the British either, of course. Brits, actually, arrived quite late in the business but took to it with enthusiasm.

Sadly, and to our shame, human trafficking, though illegal, has not been eradicated completely even today.

Alexander, quite legally, made a great deal of money and openly delighted in the sense of power it gave him to manage this side of the business. His last will and testament covers ten densely-written pages, but please note that not all his wealth came from slave trading. The current Dalvey business certainly owes nothing to slave-trading wealth. Alexander and Elizabeth had no children of their own to inherit the fortune and, inevitably, it was quickly diluted as the title passed to various relatives and their families.

The Oswald Group maintained their control of the island from 1748 to 1785. Now all that is left is a ruin but it is being conserved as a monument to a past that cannot simply be erased from our shared histories.

Capital accumulated by Alexander was further invested in Scottish forests and fisheries, Greenland whaling and land and property speculation in Scotland, Nova Scotia, Florida and Jamaica.

The scope for further investigations into his multiple business interests and travels is enormous.

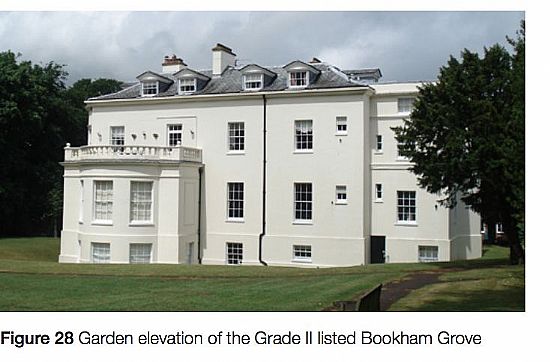

Amongst the numerous properties he acquired was Bookham Grove Manor in Surrey as well as keeping a London town residence. Elizabeth never had children of her own but she must have been kept very busy managing several households efficiently.

The Reverend Samuel Cooke

Intriguingly, the Vicar at Great Bookham was Samuel Cooke, the godfather and relative of the novelist Jane Austen. Jane is thought to have written Emma whilst visiting the vicarage and a maidservant there went by the name of Elizabeth Bennet but this would all have been after Elizabeth Cooke had died. Whether Samuel was a relative of Elizabeth Cooke, however, I have not been able to establish so far.

Family Networking

Alexander helped a number of other Grants to enter the world of commerce. One of these was young Charles Grant of the Sheuglie Branch of the family but who had been brought up by an uncle in Elgin. He was to make his name not only in the East India Company but also, ironically, as one of the members of what became known as the Clapham Sect who worked so hard for the abolition of slavery.

By the end of the 1750s Alexander had contracted to supply His Majesty’s ships at the Halifax naval station. This was something that may well link him with Robert Grant and Co later from the Ballindalloch/Carron families. Robert, also working in London, was the agent responsible for sending so many young men from this area out to the Canadian fur trade. At present this connection needs further research.

Parliament

Throughout his life Alexander’s ambition was not just to accumulate wealth but to gain family prestige and power in the Union. To this end he lobbied successfully for the restoration of the Dalvey baronetcy which had lapsed. The title was given back to his father and then passed down through the family.

Old Dalvey in Cromdale was now superceded to match the restored title. Alexander bought a fine estate called Grangehill near Forres which he proudly renamed Dalvey.

The Georgian Mansion of Grangehill near Forres that Alexander purchased and renamed Dalvey.

This was not what he considered his own home whilst he lived, however, because his interests remained where his influence could be most effective. However it gave him a foothold that would allow him to stand for Parliament.

For this purpose he, also, purchased even more land in Moray, Nairn and Inverness-shire which enabled him to contest the 1754 election which he won after an acrimonious struggle with his neighbour, Capt. D. Brodie.

Under the protection of Bute this advanced his mercantile career even further because his contacts enabled him to obtain army contracts in the Mediterranean, the West Indies, America, Africa and India.

Again this is a field of his activities that could well reward research.

Lady Haden-Guest says that “As an authority on colonial commerce, he attended the Board of Trade on 29th February 1760 to give his views on Jamaican currency and acted as agent for his friends in America in their dealings with the Board”.

The mention of friends is one of the golden keys to Alexander’s success. He was shrewd, sociable and loyal to the extent of being pelted for supporting Grenville by an angry mob as he left the Royal Exchange on 15th November 1763.

He lost his seat in parliament in 1768, dying just four years later.

Final Years

Professor Hancock describes his last years like this

In 1770 Grant turned his business over to three relatives [was this Robert, William and Alexander Grant I wonder?], but almost immediately he felt he had made a mistake and one year later returned to his counting house. Yet his presence was fleeting. In June 1772 he was ‘in a dangerous way’ and in late July he was speechless. He died on 1 August at his house in Great George Street Westminster, of ‘a total and gradual decay of nature’. His body was carried on a fishing smack to his home at Dalvey House near Forres, and buried on 1 September alongside his father.

Dame Elizabeth lived on for another 20 years but never remarried. She died at Upper Charlotte Street in St Pancras parish and her will with its codicil was proved 1 August 1792. At present I have not been able to find where she is buried nor the precise date of her death.

It is obvious that a life so varied and involving such wide travels and interests cannot be properly condensed into a mini biography without some distortion. “Citizens of the World” offers much more detailed information though there is still plenty of room of further researches into the other areas of Alexander's activities.

Like many of the mini-biographies on this website, this can only be an introduction to a very intriguing story.

The most important source for the life and work of Alexander Grant is David Hancock’s “Citizens of the World” first published by the Cambridge University Press in 1995. This was a ground-breaking study and is still a major text in this field.

Douglas J. Hamilton's "Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, 1750-1820: Manchester University Press 2005 has further insights into this trading scenario.

Alan L. Karras "Sojourners in the Sun", Scottish Migrants in Jamaica and the Chesapeake 1740-1800" has been partially accessed by me online only.

For Alexander’s political career I am indebted to Edith Lady Haden-Guest’s account in “The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1754-1790” ed L. Namier et al 1964 and published by Boydell and Brewer also accessed by me online.

Two important University website collections also offer much detail.

Aberdeen University’s “North East Story”, Scotland, Africa and Slavery in the Caribbean is well illustrated and accessible.

London University’s “Legacies of British Slave-Ownership” is a growing data-base which is the result of painstaking on-going research.

David Alston's website is a growing and invaluable resource for the study of this whole subject in this locality and can be accessed at spanglefish.com/slavesand highlanders/

I have not yet found anything helpful about Alexander’s other business enterprises and would be grateful to know of other works that would help others to delve into those matters.

A number of letters are to be found under GD 248 in the Scottish National Records which do allow us to hear Alexander’s own voice and can be found by doing a search on his name. It is important to remember that there are a number of Alexander Grants of Dalvey who will come up on such a search though.

LIBINDX online gnealogical Search will pull up a number pages which are helpful for the family and places associated with Alexander in our local context.

The story of the original and later Dalvey lines can be found under the Clann Donnachie and Clann Chiaran pages of the Clan Grant Society USA. compled by James Grant. The original pedigree can, of course, be found in Fraser’s “Chiefs of Grant”.

Jamaican Family Search is helpful in sorting out a few of the Grants who lived and worked in Jamaica.

British History On Line has useful and accessible information for the general reader about The Aldgate Ward. It is taken from “A New History of London including Westminster and Southwark “ R. Baldwin pub, Lodon 1773 though that is a year after Alexander’s death it is very close to his time there.