Robert Grant 1720-1803

Robert Grant was born in 1720 in a modest hill farm called Hillockhead on the Elchies Estate about three miles from Rothes overlooking the Estate of Arndilly with its renowned fishing beats on the Spey. Both estates were Grant-owned.

Photo of the Spey near Rothes courtesy of Arndilly Fishing. Hillockhead was on the left of this picture.

Although his father, Alexander, was a struggling hill farmer he had plenty of potentially helpful relatives. His paternal grandparents were John Grant of Phonas and Margaret Leslie. His mother was Margaret Grant of Tommore whose brother, Robert, was factor for Ballindalloch. Connections with the neighbouring Arndilly Grants are not clear but it may be through them that two of the key London merchants in our story, Robert and Alexander Grant got to know one another. There is much to learn about these connections.

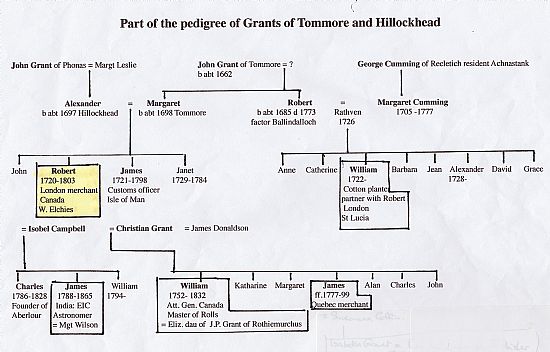

The chart below should not be seen as definitive but as a work in progress. It is an attempt to show how important just one family network became, through commerce and wealth creation to political political power and social status, in the migration story of this area. It is far from complete.

With his family connections Robert would have had military, medical and mercantile options for a career at the time. At present his education has not been traced.

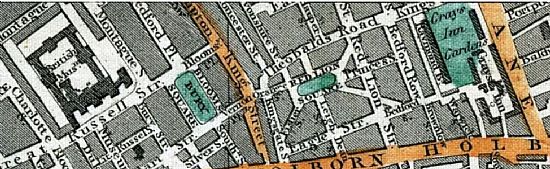

He only leaps on to the stage of our known history in the early 1750s when he was running a thriving company in the Holborn area of London where lawyers and merchants made mutually handy neighbours.

He lived and operated in a narrow alley called Warwick Court at first. If he is to be identified with one of the founder members of the The Highland Society of London in 1778 he still gives his address as Warwick Lane. He at 31, Red Lion Square however in the few letters we have for him until he retired to Wester Elchies in 1783, to which he went as the owner no longer as a "poor-relation" tenant. There is much to distentangle still about his life.

An engraving of Red Lion Square about the time Robert moved there. The watchtowers at the corners of the railed and gated gardens were there to prevent “fly-tipping”. Edinburgh suffered from the same obnoxious problem of waste disposal until habits changed and proper sewers and rubbish collections were provided.

Red Lion Square has had a very varied history. It takes its name from what was, once, the biggest hostelry in Holborn. There is still a thriving Victorian pub using the same name on the site.

The square itself has seen much change, not least because of war-time bombing which certainly destroyed the buildings next to No 31. Subsequent rebuilding may also have caused the demise of No 31.

Part of map showing Red Lion Square in 1841. Both this and the photo below come from Bradshaw’s Hand Book to London online.

There are a few buildings that remain to give an idea of the style of property in which Robert was able to live and work when in London and from which he would send out so many others to make new lives abroad.

Two 18th century houses which have survived in Red Lion Square. No 17 on the left was later the home of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In a home like one of these Robert lived and operated when in London.

The square has had a rich and varied cast of occupants and dramas. One gruesome charade involved the embalmed body of Oliver Cromwell which had originally been buried with much kingly splendour in Westminster Abbey. After the Restoration the body was exhumed along with those of the other regicides, and put “on trial”. Having been found guilty, the remains are said to have been dragged through the streets to the Red Lion to “pause for a last farewell drink” before being taken for “execution” at Tyburn. Some Parliamentary loyalists believed that Cromwell’s body was secretly buried in the square and a monument with an unintelligble inscription placed there whilst another corpse was substituted for Cromwell.

The story of these events in Red Lion Square is unlikely to be historical. The "trial" and posthumous “execution” of the regicides' corpses is affirmed. It must surely be the most grotesquely uncivilised revenge drama in British history. What Robert Grant, in post-Culloden times, thought of that reported bit of the Square’s past we will probably never know.

Next door to Robert at No 32 lived a solictor, Sharon Turner. He was also a prolific author who took on himself the superhuman task of writing “The Sacred History of the World”.

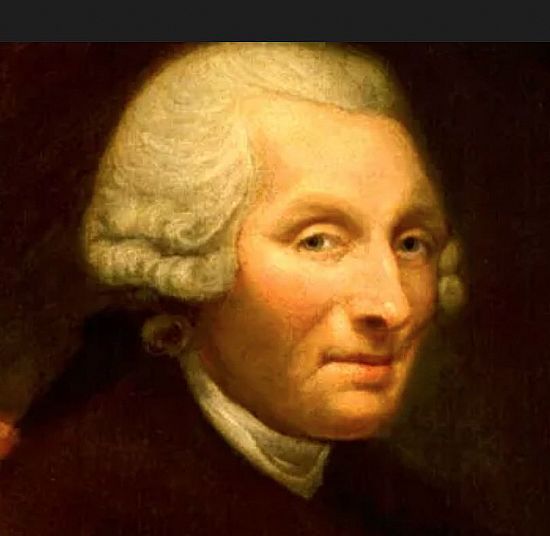

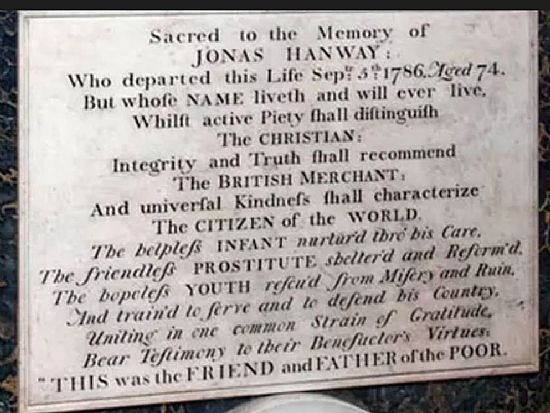

One renowned character who lived nearby was, indeed, important to Robert’s story. He was Jonas Hanway. He died here in 1786 after “a life of travel and benevolence”.

Head from the portrait by James Northcote of Jonas Hanway painted not long before Hanway's death in 1786

Hanway's memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey.

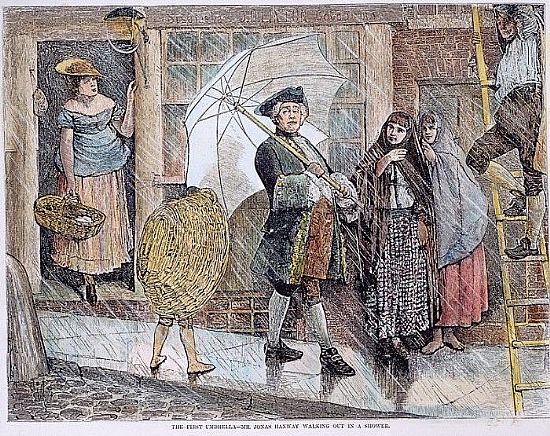

It is not, however, by his philanthropy that he is usually remembered today. He is reputed to have been the first man to walk the London streets with an umbrella over his head. Cabby drivers and others saw this as effeminacy and tried to intimidate him. But Jonas was man enough to continue with his sensible brolly which would eventually become as much the symbol of the London business gent as a bowler hat.

A wood engraving from 1871 in the Granger Historical Archive.

From the point of view of our story Jonas Hanway is most important because he was the victualling commissioner for the Navy.

Halifax Nova Scotia

There are tantalising glimpses of Robert Grant in Halifax, Nova Scotia as well as London in the 1750s to the extent that it is hard to know exactly how to fit together his presence in both London and Halifax in any proper sequence.

Halifax was the brainchild of the British Board of Trade and Plantations and is named for the Board's head, George Montague, Earl of Halifax. It was to be the spearhead of an attempt to regain control of the territory from the French. The French had technically ceded it in 1713 but the British had neglected to follow up on that so that it had reverted to being known as Acadie. The expedition was planned to be assertive but not to face the French directly. Montague proposed that it should be implanted on the Mi’kma’ki.

Out of respect I try to follow the convention of using “the Mi’kmaq” for the people as a whole, “Mi’kmaw” when speaking of someone in the singular or adjectivally and “Mi’kma’ki” to refer to the homeland of the people. If I get this wrong I will be grateful for correction.

The British incursion would be opposed by the French (also indirectly) through the agency of a highly politicised priest, Abbe le Loutre. He manipulated the fear and anger of the Mi’kmaq to mistrust British treaties, with good reason, and to make war. Military and naval strength were on the side of the British so Le Loutre's war was, inevitably, a guerilla one.

The hatchet was eventually buried in the guerilla war with the Mi’kmaq with the help of another French Catholic priest who well deserves to be remembered Abbe Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard who was invited by the then Governor, Charles Lawrence, to assist in the peace-making for Halifax in 1760-1761. Maillard was hosted and cared for during his stay by the Anglican vicar in the settlement, the Reverend Thomas Wood, another positive sign of a new conciliatory spirit in a situation of conflict.

In 1749 Lord Edward Cornwallis arrived with a considerable military and naval force as well as 1,176 potential settlers and their families who were quickly followed by a further 151 migrants. They had been enticed by the promise not only of land but of free passages, free supplies for a year and free military protection. Understandably such a force and number of settlers arriving was considered by those in situ as an invasion.

Edward Cornwallis in an etching by John Giles Eccardt after a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynold. 1756. A controversial figure whose policy of eliminating the enemy as used at Culloden was also applied to the Mi'kmaq with dire results.

Intriguingly amongst the “gentlemen” who are listed as settlers by Thomas Beamish Atkins (the early archivist and historian for the colony) were three Grants. John, William and Robert all said to be doctors. John is not identified further at present though he could be Robert's older brother. He remained in Halifax the longest. William is not mentioned at all later. How, or if, the three were related is not proved but it seems very likely, which would make them all opportunist migrants from this locality.

If Robert is fully identified as Robert of Hillockhead then this would mean that, like Alexander of Dalvey, he had some medical training before becoming involved in commerce.

Few of the settlers were prepared to be genuine pioneers who could fell trees and build log cabins and begin to ensure a food supply. Yet this was what was required. Some assistance had be sought from the French as a result.

A very readable account of the early days of Halifax can be found online. "Early settlement in Nova Scotia - a History Refresh" by Leo J. Deveau 2018.

In January 1752 John and Robert Grant were amongst those petitioning the Council to look out for a proper place for a Bridewell or workhouse to be built. A good number of the settlers had proved to be anything but pioneers. You may notice the prominence of the gallows and the stocks near the harbour in this coloured etching if you enlarge the image.

In July of that same year we find both John and Robert listed amongst those “heads of families” who had been in the colony since 1749. John has three people in his household over sixteen and 2 boys under sixteen whilst Robert has 3 adults, 1 boy and 2 girls. This may mean that Robert already has a wife and at least three children. His highly unusual marital arrangements will be considered later.

Although in 1757 the British were said to be masters of the province of Nova Scotia, one officer wrote home that this was “only an imaginary possession”. It must have been during this time of highly insecure tenure that Robert Grant Esquire was elected to the Provincial Council. Two years later when the Naval Yard was being established Robert was noted as being abroad when the Council met on the 16th August 1759.

It looks as though Robert quickly grasped the opportunities offered in the colony for commercial gain and that he was well-placed to take advantage of that. To what extent he was operating in Red Lion Square whilst resident in Halifax is not at all clear and needs much more research than I am able to undertake.

Victualling the army and navy would have been a very profitable enterprise. In 1757 there are complaints to the Council about great quantities of rum being sold to the soldiers by unlicensed traders. The following year when James Wolfe was quartered in Halifax he threw a party before leaving for the Seige of Louisburg which involved 70 bottles of Madeira, 50 of claret and 25 bottles of brandy.

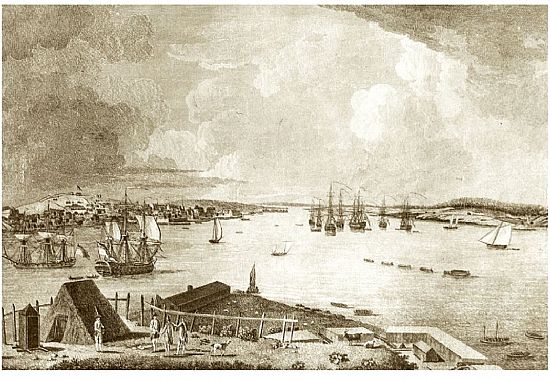

The fleet gathering in the harbour at Halifax before setting off for the Seige of Louisberg or, perhaps, for the battle of the Plains of Abraham.

Wolfe and his troops were in Halifax again before the battle of the Plains of Abraham. The strategic importance of the long bay harbour was fully recognised and by 1759 the Naval Yard was fully established. Robert looks to have seized the opportunities that the hostilities offered and built up a mini trading empire. Much work is needed to corroborate all this though and to see how his London operation and his Nova Scotian business worked together.

It is possible that Dr. William Grant went back to London to set up a successful practice. Later, whilst visiting his relatives in Speyside, he may have been called to the birth of his namesake who would become Master of the Rolls.

On the 12th March 1761 Robert “had finished a new contract for the Navie in North America”, most likely at Halifax and was considering going out himself to see it through.

Instead he sent young William Grant of Blairfindy who was not a near relative but came from the same locality as the Tommore Grants and was known to be a fluent French speaker as were many of the Glenlivet Catholics who wanted to obtain higher education.

By 10th February 1763 he was calling for more local lads to go out, writing that “I can take care of 3 or 4 lads each year without it being any loss to me and hope to give as good an account of them as those I have already exported, who have all been particularly lucky”. Identifying any of these lucky lads positively would be a great help.

By 1767, however, he was increasingly worried about all the debts and the lack of business acumen of William Grant of Blairfindy. This will be covered more fully in the lives of William Grant of Tommore and William Grant of Blairfindy, just as Robert’s connection with Alexander of Dalvey will be dealt with yet again when looking at Charles Grant of Sheuglie.

Quebec

Robert established another trading base in Quebec at the conclusion of the Seven Years' War. His merchandise from then onwards must have included furs.

Quebec City had been a thriving French City before the war. It was badly damaged during the fighting but that offered merchants even more opportunities to profit from the rebuilding and redevelopment of the city.

Co-operation with the French was vital. Scots independent traders were well-placed for this. They could work with their French counterparts through small partnerships. They took a greater risk, however, since they were not backed by the government like the Hudson Bay Company.

Few Scots merchants operated alone and Robert is known to have been in partnership with an Alexander and a William Grant. This trio require much further research especially Alexander so it is best to leave the questions of Robert Grant and Co as open-ended at present.

It was to Quebec that Robert’s nephew, William, came in 1775 and commanded a force of volunteers in defence of the city against the Americans. William became briefly Attorney-General of Canada before returning to London and eventually rising to become Master of the Rolls.

Robert also increased his wealth from further Naval contracts as the American Revolution threatened.

The Rhode Island Historical Society Archives retain a number of letters from Robert in London between 1772 and 1776 offering to supply “his Majesty’s ships and vessels, as shall come to New England, and be in want of provisions, with wholesome sea victuals, fit in all respects for the service of his Majesty’s navy”.

There are precise details of what that would consist of and the price that would be charged. This is a most valuable collection of documents for anyone wishing to delve further into Robert’s life and work or for those interested in economics at the time. They can be accessed on line in “The British Fleet in Rhode Island” by George C. Mason 1885.

Mason speaks of the link between Alexander Dalvey and Robert Grant via Rhode Island contracts though he is mistaken when he assumes that Robert was Dalvey’s son.

"From the time that the Squirrel was sent here, in the autumn of 1763, up to the opening of the Revolution, there was seldom a day when there was not one or more vessels of war on this station. How these vessels were victualed I have now the means of stating. When ships were sent to America, it was necessary to provide regular supplies of provision for them while on the coast. To this end a contract was made with some party, who was known as the Victualing Agent, and who had his assistants in the Colonies - one …in Boston, one in Halifax, one in Newport, and one in Charleston. The victualing agent at the time of which I am writing was Sir Alexander Grant, who soon after retired from the office, and the appointment then was given to his son, Robert Grant. There were two contracts, which were renewed from time to time; the one known as the “beef contract”, and the other was for general ship stores…”

Mason goes on to give two illustrations which make very interesting reading but are too long to be quoted here.

Robert, like Dalvey, invested money in a number of properties. He retained his house in Red Lion Square (presumably as well as his Halifax and Quebec properties) and acquired the estate of Wester Elchies in 1783 from James Grant of Carron. Nothing remains of the house today as it was demolished in 1967/8. To this he added other old Grant properties, Carron itself, and finally Knockando and part of Ballintomb.

An old postcard of Wester Elchies which was later demolished.

Carron House. Photo Geograph. This photo may actually be of Laggan House and the old house of Carron may have been replaced by a single storey building elsewhere. Clarification will be welcomed.

Robert Grant, born at Hillockhead farm, was able to loan the Bank of England £6,000 in 1781, offer a massive £30,000 loan to the government in 1797 and make a further gift to the Treasury of £1,000 in 1798 as “a voluntary contribution to cover assessed taxes for the defence of the country”. Not bad going for a lad who had set out from a small farm near Rothes with very little money in his pocket to make good, even though he had had influential relatives to help him.

Robert’s family life may also be described as out of the ordinary.

Robert’s will names his trustees as his wife Isabel Campbell; William Grant, Master of the Rolls [his nephew]; General James Grant [Ballindalloch]; Sir Archibald Grant, Monymusk; Alexander Donaldson Esq, merchant; Charles Grant, collector of Customs Martinique; Major John Grant of the Invalids; and Colonel Louis Grant of Auchtermark. In itself this forms a very powerful network of inter-related associates. It also raises the possibility that the so far unidentified Alexander in partnership with Robert was not a Grant at all but a Donaldson.

His legitimate children with Isabel are Charles who inherits the property and title and who would go on to create the village of Charleston of Aberlour, William, Isabel and Christian who inherit £5,000 sterling each and Alexander, William and Peter who are given £4,000 each. Most of these children seem to be still very young so the trustees are instructed to use some of the money for their education.

There are, however, a few other children who are mentioned in the will and provided for by annuities of £100 per annun and £80 per annum for life. They become clearer in a codicil which I have not been able to trace myself.

A website, devoted to William Grant of Carron, was sent a copy of this document. It was dated 16 May 1801. It lists, Charles, James William, Alexander, William, Peter, Isabel and Christian but after that are a list of other children. They are:-

“Frederick Grant presently a student at Edinburgh University.” He can definitely be traced as a lawyer in London later and his father is named in legal records as Robert Grant, though his mother is not identified.

“Robert Grant in the East India Company’s Civil Service in Bengal. John Grant, late merchant in Halifax, N.S. presently residing in London.

Charlotte Grant, presently residing in my house in London.

Her sister Louisa Grant, also residing in my house in London,

Ann, sister of aforesaid Frederick Grant, Mary Grant her sister, Elizabeth Grant her sister.”

This seems to indicate two separate illegitimate families living together in London one associated with his time in Halifax Robert, John, Charlotte and Louisa. The other children seem to be from a more recent relationship in London and consist of Frederick, Ann, Mary and Elizabeth. The mother of the first family is thought to be Jean [Jeanne?] Jollin and of the second family, Hannah Addis, born in London about 1788, both of whom are left annuities of £40 in Robert’s will.

More about some of these people can be found on the William of Carron website already mentioned. Jean/Jeanne Jollin's antecedents are, at present, unresearched, but could well have some Mi’kmaw heritage. Nevertheless it is one of their children that proudly carried on his father’s name, Robert.

That a respectable merchant in London was able to live harmoniously with two illegimate wives and their children and still acknowledge them once he had made a marriage that was more dynastically acceptable raises questions to which we will probably never have answers.

This story has nothing of the secrecy and scandal of the Deacon Brodie story. The children are openly acknowledged, though Jean and Hannah are mentioned in the will, tucked discreetly in amongst the faithful servants, but all are cared for in different degrees and were assured of the opportunity to make good careers and marriages for themselves.

In addition to caring for his own children Robert had also taken on the care of his young nephew, William, when his brother James had died. It remains to be seen if he took on the care of all James' children at the time or not. More of that arrangement in the mini-bio of William Grant, Master of the Rolls.

It must be obvious that there is still ample scope for serious research into Robert Grant of Hillockhead and Elchies.