SCHOOLING THE ADVENTURERS

There have been many claims for the superiority and distinctiveness of the Scottish educational system as the key to the success of the Scot abroad.

There is also a much-loved myth of the poor “lad o’pairts” rising out of poverty because the Scottish social ethos was more democratic than the English one.

Scottish Calvinist notions of “making good” have also been claimed as a key to the effectiveness of Scots' commercial and political imperialism.

Stereotypes provide handy labels but can often be more confusing than enlightening and can lead us to drop unguardedly into the swinging bogs of intellectual complacency.

Current discussions about our involvements in slavery and its consequences are a healthy challenge to our comfort zone of self-praise.

It is important, however, not to disregard the stepping-stones of truth we can find along our humpy paths of research looking for historical identities and motivations.

There are, indeed, some remarkable “success stories” for Scots who were willing to risk everything exploring new worlds intellectually, physically and socially.

This article can only offer a few thoughts for consideration about motivations, skills, opportunities and facilities.

It deliberately focuses on just one, rather obscure, rural school as a possible paradigm.

I hope this is both interesting in itself and that it also opens up a chink in our sometimes rather shuttered vision about the value of “our culture” and “our civilisation” for personal, social and national "success".

THE SCHOOL

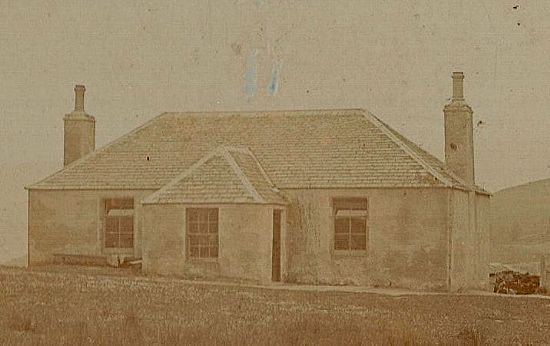

Tomachlaggan School, Kirkmichael, Banffshire

An early photograph of Tomachlaggan School in Strathavon:

Photo: Courtesy The Tomintoul and Glenlivet Discovery Centre

Is it possible that this simple, one-roomed building with a fireplace at both ends, on an exposed hillside in the highlands of upper Banffshire, has links with the imposing old College Montaigu in Paris and the vast library of ancient Alexandria?

Impossible? Let's see.

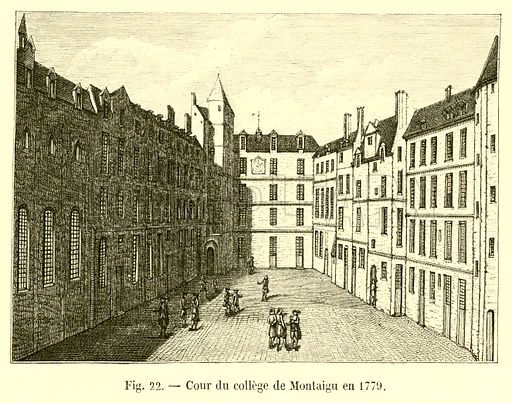

College Montaigu in Paris

A much-loved part of Paris, which has retained its largely medieval character, is still known as the Latin Quarter.

It was here that many young Scots came to study in the fifteenth century.

They entered an international community of scholars who used vernacular Latin as their common language.

One of these young Scots was Hector Boece or Boyce, whose name is sometimes Latinized to Boethius.

This can be confusing as there was a famous 6th century Roman senator and philosopher, Boethius, who wrote "The Consolations of Philosophy".

Hector Boyce/Boece came from a good Dundee family and had chosen a career in the church.

Portrait of Hector Boyce by an unknown artist

His preliminary studies had been undertaken at the local grammar school and then at the recently founded St Andrew’s University before he headed to the College Montaigu in Paris.

Montaigu was controversial both for its zeal for clerical reform and its rather punitive methods by which it enforced its ascetic ideals.

It is, perhaps, important to remind ourselves that calls for reform were widespread and very diverse in the church at this time and had not yet become polarized into outright politico-religious warfare.

Both Desiderius Erasmus and Ignatius of Loyola studied briefly in this College as they tried to find answers to the need for change in church thinking and behaviours.

Amongst the Scots' teachers involved in these debates in Paris were John Mair from Berwickshire and the near blind Robert Wauchope from Niddrie, now in Edinburgh.

Mair, (Mhor sometimes called Major), is usually described as a rather traditionalist scholastic theologian.

He came back to Scotland to teach at the recently founded universities of St Andrew's and Glasgow, the first two Scottish universities.

Mair, was, perhaps, most influential here in Scotland, in the long term, by his emphasis on the importance of historical tradition to both religious and national identity.

It was an approach that was to be followed by Boyce and, later, by George Buchanan very effectively for their time if not to the satisfaction of modern historians.

Wauchope became a Papal theologian at the Council of Trent and worked mainly on the Continent.

He was also given the impossible task of heading the see of Armagh in Ireland after the political climate had become completely hostile to Rome.

His influence in Scotland lies mainly in his ardent promotion of the Jesuits and the value of their Spiritual Exercises and education for church renewal.

Locally, this led to James Gordon of Huntly becoming the first leader of a steady stream of Scottish Jesuits who included St John Ogilvie of Keith.

Princes of the church (bishops) and of territory (nobles and lairds) were often from the same family and bound together by the patronage system of government. Kings, at the apex of that system, understandably, took a keen interest in the progress of these reform theories and movements. James IV, V and VI of Scotland were no exceptions to this.

James IV chose to appoint Hector Boyce of Montaigu College as the first Principal of the newly established King’s College of Aberdeen University in 1500.

This new Scottish University was, as a result, academically modelled on its Paris counterpart.

King's College Aberdeen University: Courtesy Electric Scotland

There may have been some understandable resentment to this foundation from the see of Moray with its centre in Elgin.

In 1522 Boyce published “The Lives of the Bishops of Mortlach [Dufftown] and Aberdeen” which, thus, firmly linked this part of the country ecclesiastically with Aberdeen and, thus, academically with the College Montaigu.

Tomachlaggan School was to send many a Latin-fluent scholar to Aberdeen over the years.

Aberdeen University was, indeed, to prove the goal of ambitious young scholars in the whole of the North.

Only very recently has the University of the Highlands and Islands extended the availability of degree-level courses through its “multi-campus” organisation. In this way it brings Elgin and other centres in the North back into academic focus.

Alexandria?

In the 1930s a local farmer and JP, who had completed all his education at Tomachlaggan school, asked his son, who had gone to senior school in Aberlour, if he was being taught “Euclid”.

The boy was completely flummoxed because he knew he was learning geometry, algebra and trigonometry but had no idea what a subject called “Euclid” was.

His father, however, knew all these disciplines through at least some of the thirteen volumes of Euclid’s “The Elements”.

The only named Greek philosopher/mathematician many schoolchildren knew by that time was Pythagoras because of that famous teetering square that sat on the sloping side of an exotic beast called a hypotenuse.

Euclid thus provides our cheery intellectual link between a key "text book" of the boys in the one-roomed Tomachlaggan school and the great Greek library of scrolls in the north African city of Alexandria to which Euclid had contributed so amazingly.

A 19th century German artist’s reconstruction of a corner of the vast library of Alexandria. Notice the importance of the roof light.

Reading has always required good lighting and was a major problem for scholars in this part of the world.

Since children were needed at the summer sheilings to mind the cattle, much of their schooling took place in wintertime and often depended on the light from the cruzie, fir-candle and, later, a Tilley lamp.

A modern replica fir-candle in its peerman holder

A table and a wall holder for fir-candles in the Highland Folk Museum. Photo courtesy of High Life Highland.

Winters were often harder than they are today too and this must have made getting to and from school in the dark, on foot, along uneven paths and through river-fords extremely difficult and sometimes dangerous.

A good training for the future bold adventurer.

Content and pedagogy

The courses and methods on offer at Aberdeen were, as we have seen, modelled on those of Paris.

This meant that the aim remained, even after the Reformation, primarily to produce ecclesiastics who would become “well-informed guides” on a shared journey towards a holy, eternal community.

Other professions like medicine, school-teaching, astronomy, surveying and literature were spin-offs of this central sacred mission.

They were not detached from that mission, however. After all God himself was often envisaged as creating the whole cosmos harmoniously according to geometrical logic as in this medieval manuscript miniature.

God encompassing the Cosmos with love.

Learning was also seen as a craft with an apprenticeship which led to becoming a Master (Magister, Mr) and the right of entry into a guild of master craftsmen, which primarily equated with the church hierarchy.

There was even a stage like that of the journeyman during which the senior student could practice teaching.

The studium was, therefore, interactive rather than being a simple dualism of master craftsmen and apprentices. This approach continued long after the Reformation in Scotland.

The scaffolding of academic learning was constructed progressively from the basic skills of “three Rs”, reading writing and ‘rithmetic (or “coontin”), through to what was known academically as the trivium of grammar, logic and rhetoric to the quadrivium which opened up a universe of intellectual abstractions through mathematics, astronomy, music and geometry.

Intelligence, as a result, became firmly equated with the intellectual skills of mental conceptualisation and this governed the selection of suitable candidates for higher education.

Early schoolmasters, with the goal of getting students to matriculate at Aberdeen University, were not expected to spend much time with those who would be unlikely to succeed in this kind of learning. Selection became a definite contributory factor to the success of the select few.

University attendance certainly set people on a pedestal even if they never actually graduated.

This introduced the possibility of the wealthy having a continued advantage. Such privilege was challenged at Aberdeen by the increasing number of bursaries which were donated by those who had accumulated wealth, to be competed for by all with the ability to do so.

In these competitions scholars from Tomachlaggan school became very proficient winners.

One room and only one teacher. Multi-age and mixed ability teaching.

The success or failure of this situation depended to a great extend on the personality of the teacher to lead and guide or to control by force. Sometimes there could be up to 100 pupils in the room at once all with varying needs and at radically different stages. Such large numbers, however, were rare and the result of a teacher becoming a victim of his own success. Students themselves then had to be mobilised to join in the teaching process. Mostly numbers were small but still required much ingenuity and clear focus on the part of the teacher and tolerance on the part of the pupils.

Education and Schooling

It is obvious that education has always meant much more than academic schooling. It can apply to all the training of our human abilities to process sensory experiences wisely.

It sometimes began in the home and in what were known as Dame Schools and personal Adventure Schools (venture schools) in which elderly widows or men who were unable to work physically began teaching the very young the rudiments of reading and counting for pennies. Very rarely were they able to teach writing.

A charming painting of a couple of children arriving late for their Dame School.

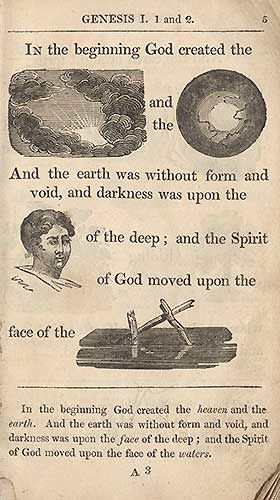

The materials they used must have varied enormously but a few horn books and, of course, the Bible (usually Proverbs) were the great standbys.

A couple of hornbooks in the National Library of Scotland

Girls would often learn to count threads and make letter shapes and numbers as they also learned to sew on bleached canvas.

Such samplers also included flowers and other natural forms which would encourage pupils to look more closely at the countryside around them.

Below is a late example of one of these. It can be seen in the Tomintoul Discovery Centre and had been sewn by Mary Grant at St Joseph’s Catholic School in the village.

Photo J. Irvine, copyright TGDC

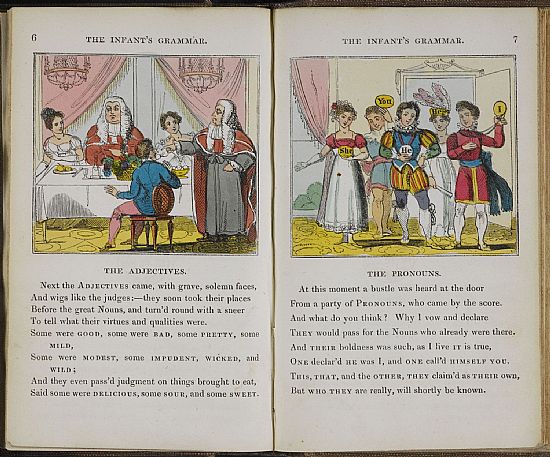

Rote learning

A great deal of learning at all levels depended on learning by heart and reciting the “lesson” back to the teacher. “Catechisms” were examples of a question and pre-formed “correct answer” technique. Books and paper were expensive but these techniques certainly made sure that people had very well trained and fully stored memories as well as shared reference structures in serious discussions.

Teachers and families would devise and use various visual aids.

Children also played games like “What time is it Mr Wolf?” and sang action songs like “One two three Aleerie” that helped to reinforce rote learning more pleasurably.

More independent learning came largely through reading especially as lending libraries were gradually set up. This early extended reading habit was particularly valuable to those Canadian fur traders who spent many winter months alone in isolated log cabins. Some, indeed, used this time for continuing serious studies.

A variety of school options

Tomachlaggan did not operate in isolation. Population growth, increasing centralisation and extension of government control and changes in land management meant constantly shifting educational requirements and provision.

Personal Adventure/venture schools have already been mentioned.

There were also side schools. These seem to be under researched as yet, but I shall be happy to be corrected on that. After 1872, when government took responsibility for education and it became compulsory for all, they were small schools dependent on a primary school that taught children who were geographically distanced from the main “elementary” school.

The wealthy always had access to private schooling either using home tutors or the boarding schools in the major cities.

Catholics in Glenlivet, Strathavon and the Enzie also somehow mananged their own schools through their priests and religious, the most famous being the seminary at Scalan. Scalan also prepared boys for university/college education on the continent.

So far I have no evidence of Gaelic schools being established in this immediate area even after “Ossian” became so fashionable.

Academic schooling for girls was a rather late addition and usually led to teacher and nurse training rather than to other professions. This is perhaps another area for more detailed researches locally. Nearly all our knowledge of early education comes via men who do just mention some later women teachers. One of the Dey family of Milton of Glenlochy looks like a good subject for further investigation on that score.

Multilingual, multicultural pupils

The local dialect of Gaelic remained the language of home until the twentieth century in some families and services were conducted in Gaelic into the late nineteenth century. This meant that children, though taught solely in English at school, had the great advantage of understanding parallel but distinct languages and cultures from a very early age especially when Latin widened the imaginative horizons of these country children even further and French became essential for the Catholics as well who would head to the Continent.

Scots' educational advantages and disadvantages?

What then can be deduced about the educational advantages and disadvantages of children in relation to their ability to “make good abroad”.

Positively

1) Education was valued by the community, supported increasingly by university bursaries, and most people were willing to make great sacrifices for it.

2) It was very focussed and competitive.

3) Even though in some respects this education offered a rather closed classical curriculum, those who succeeded in it had to develop talents in both the humanities and sciences, even though sometimes unevenly.

4) Children who had ability were pulled and pushed and motivated towards individual achievement.

5) Teachers and pupils needed to use their ingenuity to make the most of their meagre resources.

6) Children held all teachers in great respect and some with genuine affection as I hope to show in the article on schoolmasters.

Negatively

1) They were often obliged to struggle over hard even to get to and from school and to overcome disease and they also had to come to terms with the early deaths of quite a number of their fellows whose constitutions could not stand the pressure. This can be seen as a positive as well, of course, but it could certainly result in a need for callousness to suffering as a defence mechanism.

2) School teachers reinforced a general acceptance of the value of the adage "spare the rod and spoil the child". However, the use of corporal punishment and humiliation could attract men and women who found it ego-boosting and even pleasurable to abuse such power. It also made "respectable" the use of force in driving labour-for-profit and the notion that some lives were more valuable than others and "deil tak the hindmost". It classfied and created hierachies of value to suit its own ends. Nothing was new or uniquely Scottish in this of course but it was to have a major impact in industry, commerce and emigration stories.

3) Bad teachers were quietly erased or passed over in the published histories like that of William Barclay's book about the schools and teachers of Banffshire published by the EIS. This gave a notion of the superiority of Scottish education as untainted by incompetence and distortions of both aims and methods of formation and correction.

4) Scholars and graduates formed an intellectual elite. Even after the 1872 Act, when education became compulsory for all, there was little meaningful provision for those considered to be less intelligent and no-one really knew what to do about those labelled "ESN" - "educationally sub-normal". We still struggle over the differing benefits of special or inclusive education.

Discipline and Drive

There is something important that needs to be faced and explored more honestly by us with regard to the relationship between socially accepted cruelty in schools and the treatment of peoples equated too often with “backward” children in the minds of sojourners and settlers abroad.

Charles Dickens satirized bitterly the “profit” and “utility” motive in education through Gradgrind the school inspector in Hard Times. He also created Wackford Squeers, the sadistic schoolmaster in Nicholas Nickleby to highlight the abuse which was accepted in the boarding school at Bowes School which became Dotheboy’s Hall in the novel.

Was Scottish education really free from such abuse?

One reported incident, in Speyside, offers a chilling parallel to the fictional boy Smike, brain-damaged by his teacher/guardian, Squeers. This real incident must have taken place in the 1830s and yet the reporter can still call the teacher "good" in 1902. Were "terrorism" and "submissive docility" really seen as educational necessities and as socially acceptable at the beginning of the twentieth century to the point of irreparable harm?

George Gillan, his teacher in Aberlour, is remembered like this by James Thomson in the couthy “Recollections of a Speyside Parish" (1902) ch XVIII

“The village school of Aberlour in my time was taught by George Gillan. A man portly in person and ‘stern to view’, he ruled us firmly and taught us well, considering the means he had. A solitary map, as yellow as a duck’s foot, and on which an outline of the eastern hemisphere was dimly visible, hung above the fireplace. As we took our turns at the fire upon a winter’s day, that old map was scanned with eyes that never wearied of tracing its outlines. What a field lay within the four corners of that tattered map for our imaginations to revel in!

There was one object that brought a realization of that far East very near to us.

A mulatto, sent by his parents to be taught and cared for by the dominie, was an object of interest to us all. For his instruction an object was occasionally brought ben from the master’s room to the school that never failed to draw all eyes towards it, namely, a large terrestrial globe. The first sight of the new planet could not have caused a greater sensation in the breast of the astronomer than did, for the first time, the sight of that revolving globe.

On one occasion the dominie, pencil in hand, was eagerly tracing the outlines of continents and seas for the edification of the eastern mind, when he suddenly ceased, and, lifting the lid of his desk, took out from the recess ‘the muckle tag’.

He placed the pencil in the mulatto’s hand, and ordered him to point out certain places on the globe; but instead of doing all this he buried the fingers of his right hand, pencil and all, amongst the long black curls that covered his head.

In the twinkling of an eye ‘the muckle tag’ was laid on the mulatto’s head. Like a man at the flail, the dominie poured blow upon blow, until the poor fellow howled like a wild beast.

Every heart in the school trembled and stood still. Never before was such a sight seen.

For the remainder of that day a subdued silence reigned in the school. The sight of the mulatto’s ebony face, covered with tears and contorted with shame (for he had reached to man’s estate), left a depressing feeling upon us all for many a day.

‘The muckle tag’ was a ponderous strap of leather about two feet in length, with the end cut into fingers two or three inches long. To harden the points, they had been slightly singed in the fire. The dreaded instrument of torture lay like a serpent coiled up in one of the pigeon holes of the dominie’s desk. It was only upon special occasions that it was brought out. ‘The little tag’ lay all day upon the top of the desk, ready at any moment. Though small in size it bit sharply.”

Further reading:

There is a vast and often contentious literature about Scottish education and the theories and mind-sets underpinning it. May I cite just one article as an introduction. It is not necessarily the “best”. That would be something that I am simply not competent to judge. However it could help to raise some of the issues that are important in our exploration together of our local area and the effects of migration in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Parimala V. Rao: “Class, Identity and Empire: Scotsmen and Indian Education in the Nineteenth Century” Social Scientist Vol 44 No 9/10 (Sept-Oct 2016) pp 55-70

Those who are particularly interested in the philosophical and religious theories of education in the Enlightenment and Industrial period in this part of Scotland might also like to investigate some of the works of George Turnbull (1698-1748) and David Fordyce (1711-1751).

Because education is now universal and compulsory in many countries everyone feels they "know" all about it and judge from their personal experience. Yet the odd thing is that it has been debated, in the West anyway, since the time of the Greeks and we still cannot find full agreement about what it should consist of and how it should be conducted.

There are a number of educators who went abroad from here whose mini-bios I hope to be able to introduce including, also from an Eastern perspective, Charles Meldrum from Tomintoul who worked in Bombay and Mauritius for most of his life. I hope we can also see how much Scottish education benefitted financially from those who put the money they had acquired abroad into educational projects at home.