Page under construction

The Highland Lady in India

Elizabeth Grant/Smith 1797-1885

A photo taken of Elizabeth Grant /Smith in old age when she had nearly lost her sight

Sense or Feeling?

Two near contemporary women writers in the Grant family, Anne and Elizabeth have left us accounts of their lives in this region and also of their unchosen sojourning abroad.

Both were intelligent, well read, conscious of the responsibilities as well as the privileges of their births and marriages.

Both had to deal with highly complex and painful situations.

Both loved the places they lived in and indentified deeply with them.

Both wrote profusely, largely for their own families to read. It is the familial intimacy into which we are drawn that makes their writing (Elizabeth’s in particular) so attractive to us still and allows us to cope with a fluency that is, now, so unfashionable.

Both became published writers out of dire financial necessity.

These two Grants can also be seen as cyphers for two prevailing polarities at the time about what was the “right and proper” way to handle human affection and emotion. Jane Austen would have used the terms “sense” and “sensibility”.

Anne Grant’s work overflows with pious “feeling” using the term made fashionable in Scotland at that time by Henry MacKenzie’s popular novel. Yet she is certainly neither weak nor exploited.

Henry MacKenzie, himself. though he was often identified with his fictional creation “The Man of Feeling”, was actually a solid man of business, a lawyer, controller of taxes and well connected to the Tory political establishment and all the “men of genius” in Edinburgh at that time. His connection with Strathspey is that he was married to Penuel, daughter of Sir Ludovic Grant of Grant.

Elizabeth Grant

Elizabeth Grant of Rothiemurchus, usually known as “The Highland Lady” on whom this mini-bio is focussed, was sensitive and sharply observant but struggled for a “ladylike” and “moral” control of her emotions.

Two portraits of Elizabeth's parents John Peter Grant of Rothiemurchus and Jane Ironside. courtesy of Mike Edwards a descendant of the Ironsides. Elizabeth is probably the child on her mother's lap and her sister Jane is at her mother's shoulder.

Two portraits of Elizabeth's parents John Peter Grant of Rothiemurchus and Jane Ironside. courtesy of Mike Edwards a descendant of the Ironsides. Elizabeth is probably the child on her mother's lap and her sister Jane is at her mother's shoulder.

Under pressure, her mother, Jane Ironside, tended to withdraw into herself and become ill or very difficult. Her father, John Peter Grant of Rothiemurchus, resorted to the “rod” when he could not deal with his children’s high spirits, misdemeanours or distresses. He could also be stubbornly dictatorial if challenged. Such parental defence mechanisms were not exactly conducive to a healthy upbringing.

Yet Elizabeth became remarkably perceptive and analytical about early childhood education and its effects on future adult coping strategies and mental and physical health.

Only one period in Elizabeth’s life is introduced here - her time in India. She also spent some time in France and most of her married life was lived happily and productively in Ireland.

Born in Edinburgh when it was at the height of its intellectual and social prestige, Elizabeth’s life should have been one of expanding opportunities. Her parents were well connected on both sides of the Border.

However, her father as a lawyer, as a Highland Laird and as an MP was worse than fushionless about his finances and unable to accept wise advice or outside control.

The family were obliged to “retire” to the Rothiemurchus estate with which Elizabeth identified most.

Photo of The Doune of Rothiemurchus today beautifully restored from its previously very dilapidated state.

John Peter was finally forced to sell his estate when he lost his seat in Parliament and even that drastic sale did not clear his colossal debts.

Without the protection of his Parliamentary immunity from prosecution he became a fugitive from the very justice he was qualified to administer.

Leaving The Doune

Elizabeth describes her final walk round the grounds of the estate with her younger sister, Mary, in her memoirs. Their planned stoicism gave way at the last gate.

“…and so to the green gate under the beech tree, with few words, but not a tear till we heard that green gate clasp behind us; then we gave way, dropt down on the two mushroom seats and cried so bitterly…Even now I hear the clasp of that gate; I have heard it all my life since, I shall hear it when I die, it seemed to end the poetry of our existence.”

Through the good offices of Charles Grant, Lord Glenelg, Elizabeth’s father had been given a chance to redeem himself and pay off his debts as a judge in India. To prepare for his new role he received (quite incongruously when you consider he was a wanted debtor) a knighthood. Such was the power of networking and patronage at the time, however. He then went to ground possibly in France until all was arranged for the voyage to India.

The Journey

Getting to Portsmouth and boarding the boat was still fraught with danger. Several times their plans nearly fell apart. It was only when they were eventually on board their boat and underway that their father was able to join them from another boat which brought him from wherever he had been hiding. It was a frightening and ignominious departure from the home country.

A portrait of the ship ‘Mount Stewart Elphinstone’ shown broadside-on with the cliffs of the English coastline in the distance. Figures are shown on deck looking towards the coast. Built of teak in India in 1826, the ‘Mount Stewart Elphinstone’ had a trading life of more than 50 years. Over several voyages she carried nearly 1,700 convicts to Sydney and Hobart, as well as emigrants to Australia. The ship took between three and five months to make each voyage and in 1849 was described by Sir Lucius O'Brien of County Clare as a ‘deplorable prison-ship’. The painting has been signed and dated by the artist ‘W. Knell 1840’. Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Their newly built vessel was named after the Scottish Governor of Bombay (Mumbai) Mountstuart Elphinstone.

The family had excellent accommodation on board and were treated well. The long journey round the Cape had its trials but it was certainly much more agreeable for them than it was for the many later prisoners who were transported to Australia on board the same vessel.

Arrival In Bombay

“We landed on the 8th of February 1828 in Bombay.

We entered that most magnificent harbour at sunset, a circular basin of enormous size, filled with islands, high, rocky, [and] wooded, surrounded by a range of mountains beautifully irregular; and to the north on the low shore spread the City, protected by the Fort, screened by half the shipping of the world”.

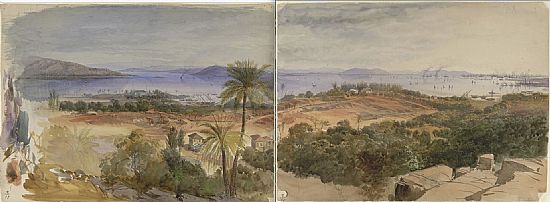

Water-colour paintings of Mumbai Harbour by Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902) in January 1870. Inscribed on the back in pencil is: 'Bombay.'

Originally, Mumbai (Bombay) was composed of seven islands separated by a marshy swamp. Its deep natural harbour led the Portuguese settlers of the 16th century to call it Bom Bahia (the Good Bay). Britain acquired the islands in 1661 when Catherine of Braganza married Charles II, as part of her marriage dowry. It was then presented to the East India Company in 1668. The second governor, Gerald Aungier, developed Bombay into a trading port and centre for commerce and inducements were offered to skilled workers and traders to move there. European merchants and shipbuilders from western India were encouraged to settle there and Mumbai soon became a bustling cosmopolitan town.

At once Elizabeth was struck by the dignity and graceful deference of the Indian servants and their ability to anticipate all the needs and expectations of the Europeans without hassle or fuss. She neither expected this nor rejected it. She simply accepted it as the way things were done there.

Her uncle had hired a house called Camballa (Cumballa) that “stood on a platform in the middle of the descent of a rocky hill, round which swept the sea, with a plain of rice fields, and a [water] tank, between the foot of it and the Breach Candi road along the beach.”

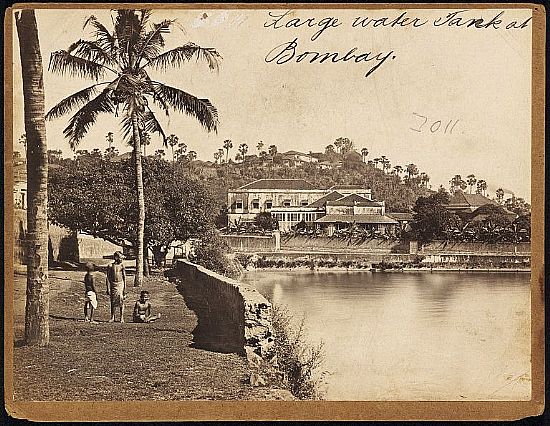

The water tank in front of this house is like the one that Elizabeth describes at “Camballa” from the Francis Frith Collection

She almost felt that she had walked into the opulent splendour of “The Arabian Nights” tales and she loved it. “There was light, vastness, beauty, regal pomp, and true affection”. The emphasis is hers. The term “affection” is used in its earlier sense of something that affects or opens up the mind and spirit rather than as a warm sentiment.

The exotic here was indeed tempered by other realities. Bedrooms were more like barns, “bare rafters and bare walls. No fastening on the doors, the bathrooms very like sculleries, the flowery terraces suspected of concealing snakes, and most certainly harbouring myriads of insects…and the tank a nuisance…at night…from the multitude of frogs - the large bull frog with such a dreadful croak that deafened us.”

She wisely recognises that in her first impressions her imagination is colouring her observations. The only other time she mentions snakes was when she and the chair she was sitting were, without warning, pulled away by the servants to reveal a snake which had nestled at her feet.

Quickly settling in she describes the orderliness of the day with its work confined to the cooler hours. Its relaxed pace was made possible by the assurance of regular pay, the social hierarchy and the sense of solidarity amongst the colonial community. The only real snag appears to have been the heat.

The Retreat

After her sister Mary’s marriage Elizabeth and her parents moved to a rather smaller property called The Retreat. It was protected from the sea winds and did not have the same view. In this more settled place she began to describe the household servants and their behaviours and distinctions of caste and religion. Fascinating though this all was to her she also began to find life monotonous. She enjoyed the social life just as she did at Kinrara when the Duchess of Gordon (Jane Maxwell) was the hostess there and she describes the people in her usual frank manner. Nevertheless she has no real responsibilities to occupy her talents except to be decorous and decorative.

One of the disavantages of the house was the Parsee graveyard on the hill above the house where vultures released the souls of the dead to a happy eternity whilst recycling the bodies. Elizabeth certainly disliked the vultures’ nasty habit of dropping their half eaten left-overs into the garden.

She was even more affronted when one decided to settle on her windowsill.

Photograph by Shantanu Kuveskar Location : Mangaon, Raigad, Maharashtra, India

An Indian vulture that Elizabeth deemed “ugly” largely, I think, because of its associations with scavanging amongst the dead rather than its actual appearance. It was not something, however, most of us would wish to admire looking at us from our window sill with no glazing between us and it.

The Power of the Indian Monsoon

The arrival of the Monsoon was an experience for which she had no precedent and she describes it very vividly even long afterwards. (I have taken the liberty of breaking up the text with a little more space and punctuation to make it easier to read. I have not changed E.G’s words.)

“The opening of the monsoon is one of the grandest phenomena in nature.

About a week ot two before the outbreak clouds began to gather over a sky that had been, hitherto, without relief.

Day by day the gloom thickened; at last the storm broke.

We were going to sit down to luncheon when a feeling of suffocation, a distant rumbling, a sudden darkness, made us all sensible of some unusual change approaching.

The servants rushed to the Venetians and closed one side of the hall, with the utmost expedition, the side next to the storm; yet they could not save us altogether.

From the wind they did - a wind, suddenly rising, burst from the plain with a violence which overwhelmed every opposing object, and while the gust lasted we could hear nothing else, not a step, nor a voice, nor a sound of any kind.

It did no harm to our well-secured apartment, but it brought with it a shower, a tempest rather, of sand, so fine, so impalpable, that it entered like the air through every crevice, covered the floor, the seats, the tables with red dust which well nigh choked us.

This was succeeded by a lull almost awful in its intensity, and the first thunder growled.

At a vast distance it seemed to rumble, then strengthening, it broke sudddenly right over the house with a power that was overwhelming.

Flash after flash of lightning glared, it was more, far more than a gleam. The rain, such as is only known in the tropicks, poured down in flakes with the din of a cataract.

On came the thunder. Again and again it shook the house, rolling round in its fearful might as if the annihilation of the world were its dreadful aim”

Camping Indian Colonial Style

On two occasions Elizabeth makes visits to the Western Ghats.

The first was to accompany Mary, now Mrs Gardiner, her husband and their new baby daughter, to the higher ground for the sake of Mary’s health.

The impressive escarpment edge of the Great Deccan Plateau rises from the narrow coastal plain steeply for around 4,000 feet. It is broken by ancient river valleys that have created deep gorges.

Elizabeth was delighted at the idea of camping in this biodiverse mountain country at the hill stations of Khandala and Lanovala.

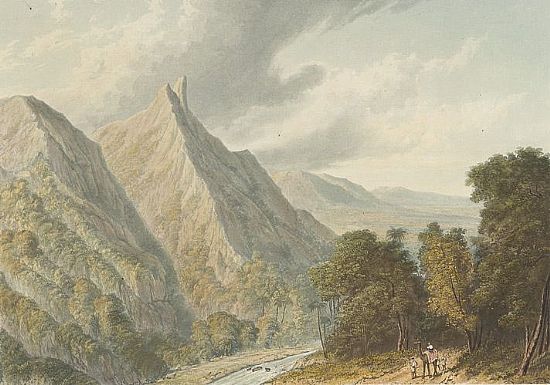

Plate 9 from Robert Melville Grindlay's 'Scenery, Costumes and Architecture chiefly on the Western Side of India'. Grindlay (1786-1877) was only 17 when he arrived in India in 1803. He served with the Bombay Native Infantry from 1804 to 1820 and during this period made a large collection of sketches and drawings. The extract below shows what the journey involved.

"The Bhor (or Bhore) Ghat is the northern part of today's Maharashtra state. It is the main pass over the Western Ghats and the primary means of communication between the coast and the Deccan. Bhor was a native state of India in the Poona Political Agency, situated among the highest peaks of the Western Ghats. Grindlay quotes Lord Valentia to describe the difficulties of travelling here: "The road has been formed ... out of a bed of loose rock, over which the torrents in winter had run with such force as to wash away all the softer parts ... to get the palanquin over these was a tedious and difficult business ... the boys were obliged to use sticks ... to prevent themselves being thrown forward ... though I walked the whole way, not only to relieve them, but to admire the sublimity of the scenery.”

This was however no simple al fresco holiday event for Elizabeth. At this time there were none of the impressive (though hardly picturesque) major trunk roads and railways that now take you from Mumbai to Pune (Bombay to Poonah) for travellers to use.

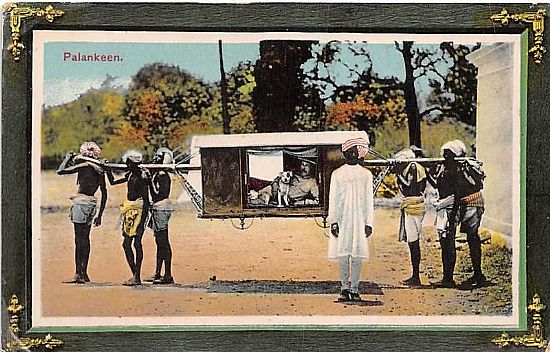

Transport was still by palanquin along steep paths that wound up the cliff edge. The journey was a test of skill, trust, nerve and physique for all involved.

Old Postcard of palaquin travel on a level gradient.

When Elizabeth finally negotiated her way into her tent on her arrival after dark she was astonished to find it equipped with all her usual home comforts including her bath. All the furniture of her bedroom had been transported ahead of her.

“It was gypsey life in Sunday suit” she said and she loved it unashamedly.

It is the wildlife that now draws people to this region (as well as the views when the mists lift). For Elizabeth, nature came rather too close for comfort one night.

“And so, I lay me down in peace and took my rest.

What waked me?

A noise, which once heard can never be forgotten - a noise unlike any other sound in nature, a growl, so deep, so low, so full, so strong, that it almost paralysed sensation.

It was just at my ear.

There was only a bit of canvas between me and a tiger”

Dibyendu Ash - The image of tiger's facial marking (Sultan or T72) had been photographed from Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India on 12.10.2014.

The Bengal Tiger, even though known to attack humans, was considered “too sacred to be exterminated” but happily on this occasion it lost interest and was chased off by all the noise that could be possibly be made in the camp - shouts, guns, pistols, pots and pans.

Mahabaleshwar

The second visit to the Ghats was at the invitation of Colonel Smith and involved Elizabeth and her parents.

It was a commonplace notion that unmarried women went to India to find a husband.

Elizabeth knew full well that she was expected to follow this pattern.

It seems that everyone had decided that the right person would be the Irish Colonel Henry Smith.

It was, however, only when she saw her mother shamelessly examining his "plate" on the table laid out for them on their arrival that Elizabeth realised that her fate was about to be sealed.

Although the contract was business-like, the prospective bridegroom could hardly have chosen a more romantic place for his formal proposal and acceptance.

“A wide plain on the top of a long ridge of mountains, not much wood near us, but plenty all round, no rising either close, with one exception, a hillock on which stood the Governour’s small bungalow.

His and the Resident’s [bungalow] a little way way off were the only houses at the Station. Everybody else, including the sick soldiers sent up there, lived in tents scattered about anywhere in small groups of from three to five and six according to the size of each establishment.”

Elizabeth and the Colonel had the pleasure of riding together each morning to get to know one another better.

“Riding, we came on the head of beautiful gullies far below us, stretching far out under the morning mist. We looked down on the mountain tops, stood above wooded ravines, which made the scenery so curious”

Rather more crowded accommodation at the hill station today at Mahabaleshwar where Elizabeth and her Irish Colonel agreed to lock their futures together. Photo . Prapti Mitra

Their plan was that they should marry at once where they were since there was a clergyman on hand and the Governor could issue the license. Most of Elizabeth’s possessions had already accompanied them to their camp site and the Colonel’s regiment was only 30 miles away so it seemed sensible not to wait for a big ceremony.

Such a low-cost arrangement suited Elizabeth’s father admirably but her mother threw a major tantrum. This forced everyone to make the difficult journey back to Bombay.

For once Elizabeth allows us to see how petulant and selfish her mother could be. She makes no excuses for her even in retrospect.

She must have known that the Colonel would lose a month’s wages being away from his regiment.

What no-one could have anticipated was that they could have easily lost the bridegroom altogether.

His horse stumbled crossing a stream on the journey and threw him. He was laid up for some time but happily recovered enough to go through with the marriage.

The Highland Lady becomes The Irish Lady

As in a fairy tale, just before their wedding took place they got news that Colonel Smith had become the lord of Baltiboys because his older brother had died.

Henry would be able to retire from the army and Elizabeth could settle in to the kind of life for which she was so well-suited.

Some new clothes also arrived in the nick of time for Elizabeth to wear for the marriage. Her husband wanted her to wear mourning for his brother after that for some time.

The wedding took place in the Cathedral in Bombay. Elizabeth was understandably rather detached from all the excitement.

“I was very much bewildered all that morning, and hardly knew what was doing till I found myself in the boat, sailing among the islands, far away from every one but him who was to be in lieu of every one to me for ever more.”

What brought her into the reality of what had happened were the words of the woman who had been her valued personal servant, Fatima.

“The first movement that occured to me was to remember Fatima’s advice - retire to my inner cabin, take off all my finery -

I had been married in white muslin, white satin, lace, pearls, and flowers -

and put on a cambrick wrapper she had sent on board and had laid ready.

The next was to obey my new master’s voice and return to him in the outer cabin, where, on the little table, was laid out an excellent luncheon supplied privately by my mother, to which, as I had certainly eaten no breakfast, I, bride as I was, did ample justice.

Indeed we both got very sociable over our luxurious repast and quite enjoyed the nice cold claret that accompanied it”.

Further Reading:

There are numerous editions of the Memoirs of a Highland Lady. Two volumes cover her early life in Edinburgh and Rothiemurchus prior to her marriage so that the story of her time in India is at the end of Volume 2.

Her life in Ireland is split into two volumes: "A Highland Lady in Ireland” and “A Highland Lady in Dublin”. The year of her sojourn in France come in between these two periods of her Irish life and are related in A Highland lady In France”. Her two editors who made this arrangement are Patricia Pelly, a descendent and Andrew Todd.

For the information on Bombay in particular I am grateful for articles in Wikipedia since I have no personal knowledge to draw on