"The Gane Awa' Land"

Alexander MacGregor Rose

[A. M. R. Gordon]

17 August 1846 Tomintoul - 10th May 1898 Montreal, Canada

It was in house in Drover’s Lane, Tomintoul on the 17th August 1846 that Alexander Macgregor Rose uttered his first cry in the household of a tailor, George Rose, and his wife Anne Innes.

An early photo of the upper part of Tomintoul village high street.

His background and early life were happy but somewhat complicated.

Anne was the illegitimate daughter of Margaret Grassick and William Innes. Anne also had a half-brother called James Grassick Blair, the illegitimate son of Alexander Blair.

Margaret Grassick finally became the legitimate wife of a warm-hearted and successful Tomintoul flesher called Alexander Macgregor (locally known as “The Grigorach”). This marriage, however, produced no offspring.

When Alexander was two years old he went to stay with the MacGregors because his mother, Anne, was expecting her second child. The MacGregors lived very close by so this would have been a quite usual arrangement. However, what was unusual, was that young Alexander so captured the heart of “The Grigorach” that he remained with his grandmother and step-grandfather. One account says he was formally adopted by them but his surname remained Rose and MacGregor was retained as his middle name.

From then onwards, however, he was known as “Young Grigorach” or “Greeg”.

The Macgregor home was comfortably established and Greeg had great freedom to make friends and enjoy all that the fine natural world around him had to offer. The disadvantage was that he came to believe that he could rely on his popularity and likely inheritance to carry him through life.

Tomintoul village school had a particularly gifted teacher at the time in James Grant who sent a stream of pupils on to Aberdeen University though, with Alexander, he had only a limited success.

The boy showed a special interest in languages (i.e. Latin and Greek) but an aversion to arithmetic. The latter was to be his undoing.

Robert Dey, writing the preface to the collection of Rose’s poetry, says that Greeg was known locally for his "sporting ability". This would refer to fishing and stalking learned from the gamekeeper, Willie Macgregor, near the head of the Avon at Faebuie. He also delighted in quick-witted repartee. Very early he developed the ability to create rhyming couplets about the foibles of his neighbours, not always to their amusement.

Dey believed his verse was particularly influenced by “locals” like William Grant Stewart, Donald Shaw (“Glenmore”) as well as by Capt Rowland Hill Gordon, son of General William Gordon of Lochdhu. There is also cross-referencing to Scott, Burns and Wordsworth on occasions but the most obvious inspiration of his verse technique lies in the rhythms of popular songs.

In Canada he eventually achieved fame for political jingles written in a kind of satirical “franglais”. One on Sir Wilfred Laurier stopped the proceedings of the Canadian Parliament whilst it was read aloud for members’ amusement. His most famous verse “Hoc der Kaiser!”, a lampoon that was used as a piece of war propaganda, was written in “Anglo-German”.

Greeg failed in the Bursary Competition which would have taken him straight to Aberdeen University. He did a little apprentice teaching at Inveravon School but then studied at Aberdeen Grammar School to try to improve his university chances. There, at the age of 17, he gained the Macpherson bursary of £20 tenable for three years. Completing his Arts Course at Aberdeen in 1867 without academic distinction he began teaching classics in a number of (unnamed) English boarding schools.

By 1870 he was the master of the Free Church School in Gairloch but was turning his mind to divinity like his life-long friend Charles Meldrum. He obtained another bursary to return to University for 4 years and in 1875 was Licensed to preach at the Nairn Free Church where Meldrum would also serve.

On the 18th November 1875 at Old Machar, Aberdeen the newly licensed minister married Mary Falconer, whose family ran a very sucessful clothing business which would eventually become part of the House of Fraser empire.

A call to the church in Evie near Kirkwall seems to have come quickly to the promising young couple.

Old postcard of Evie

It was here that he finally felt the full impact of his mathematical deficiencies. Although he was a popular preacher and drew large congregations, he quickly found himself on the brink of bankruptcy. Excessive convivial hospitality seems to have been at least part of his downfall though Charles Meldrum tried hard to defend his friend’s reputation even beyond the grave.

Drinking songs certainly featured strongly in his adult poetry. One very early one celebrates “Heilan Whiskey” (sic) i.e. The Glenlivet and has a dig at some ministerial hypocrisy about alcohol.

Teetotallers may get up a squeel,

And try to prove wi’ a’ their skeel.

The first distiller was the Deil.

And fat he brewed was whiskey;

But haith, we canna’ credit that,

Besides, his fire would burn the maut,

And spoil the broust o’ whiskey.

There’s the Reverend Dry-as-Dust

Declares it’s hand in hand wi’ lust,

And that it fills him wi’disgust,

The very sicht o’ whiskey;

But haith, gin ye but kent the truth,

He likes himsel’ to quench his drouth

An’ swill the sermon frae his mouth

Wi’ draps o’ Heilan whiskey.

There’s the Reverend Mealy-Mou’

(Wi’ reverence be it spoken, too,)

Wad gar us think ‘twad mak’ him spue

To pree a drappie whiskey;

An’ yet his neb is like the rose,

The blossoms on his face disclose

That he’s nae fae to Atholl brose,

Nor yet tae draps o’ whiskey.

So, spite o’ what the parsons preach,

Doctors and teetollers teach,

Here lassie! Just go ben and fetch

Another gill o’ whiskey.

An’ may Minmore, for many a year

Distil the drappie strong and clear,

Oor cares to droon, oor hearts to cheer

In pure, unchristened whiskey.

However, the erstwhile Reverend Alexander Rose, shorn of the protection offered by his ecclesial status, now decided he had no alternative but to get out of the country as quickly as possible.

As a result his wife and two baby sons were obliged to return to the Falconers in Aberdeen.

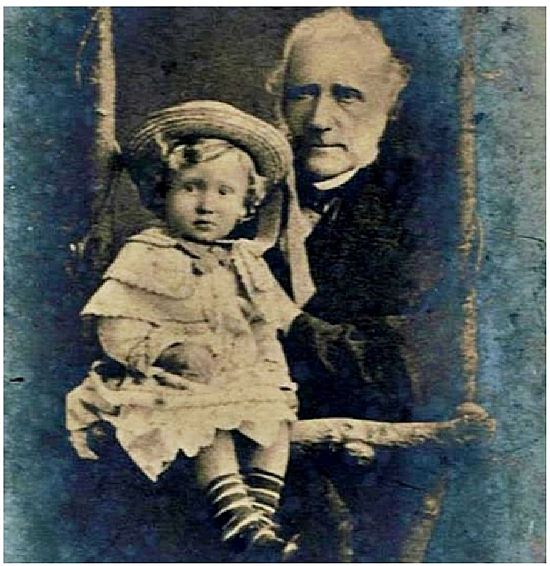

There is, at present, no way of knowing how his wife felt about this whole episode but quite a bit is known about the sons who were raised by the Falconers. The photo of baby George with his grandfather is an ironic mirror image of his own father’s situation at the same age though with much better consequences.

George Falconer Rose with his maternal grandfather

Mrs Rose, Mary Falconer, with the two fine sons she brought up without her husband

George Falconer Rose became a successful engineer working in the jute mills in India. The excellent Glenbuchat Heritage website says, “He obviously made a lot of money and acquired estates in Strathdon and Deeside. He is recorded as ‘George Falconer Rose of Auchernach and Rhinstock and Wester Sinnahard, Strathdon, co. Aberdeen, MIMech. Seats — Auchernach, Strathdon, Aberdeen; Tullich Lodge, Ballater’. He married successfully and had a large family.”

Alexander jnr, gained an MB from Aberdeen plus a diploma in Public Health and then went into the RAMC serving first in Bermuda but when war broke out he was in France and later Germany. He was taken a prisoner but eventually repatriated, returning once more to serve on the front line. He was awarded a DSO for his services. He married and had two daughters and one son. The family lived at Birchwood, Cults on Deeside.

The boys' father Alexander Magregor Rose, however, a fugitive from both his unpaid creditors and his vocation, crossed the Atlantic from Glasgow on 10th of June 1879 to begin his life again alone in New York.

His poem “Farewell Tomintoul” may allow us a little insight about how he might have felt though it was written earlier for someone else. When John Macdonald sings a version, it is far from being a sad lament, however.

FAREWELL TOMINTOUL On the left is the version that is published in Dey’s collection of Rose’s poetry which he says was written for Mr James Brodie (not identified).

On the right is the version as sung by John MacDonald, ‘The Singing Molecatcher’ from Dava (learned from John Coutts, Railway Surfaceman, Dava) With thanks to Seumas Grannd and the School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh University.

In order to allow the direct comparison the type size has had to be reduced so please enlarge it on your screen if it is not legible.

Farewell, Tomintoul! for the hour’s come at last Farewell Tomintoul for the hour’s come at last

When I only can think of the joys in the past When I only can think of the joys in the past

For destiny bears me away from the glen; For destiny bears me far from the glen

Where dwell bonny lassies and kind-hearted men. Farewell bonnie lasses and kind-hearted men

What though in their spite petty minds have decried thee, Strathavon your hills and your valleys shall be

And said, with a sneer, they could never abide thee; Ever dear as the home of my childhood to me

I am sure that in this I shall not be alone But now I must leave you and far must I roam

When I say I am certain the fault was their own. My heart will aye be in my dear Highland home

As for me, I can say with my hand on my heart To lofty Ben Rinnes I now say adieu

I’m loth as can be from Strathavon to part; In a far foreign land I’ll be dreaming of you

And its hills and its streams and its valleys shall be To the swift flowing A’an I now say farewell

Ever dear as the home of my childhood to me. Across the wide ocean thy beauties I’ll tell

I have found hospitality, kindness and truth

To be deeply engraved on the hearts of its youth,

And I know you can always with safety depend

On them aye standing true in the cause of a friend.

I shall always remember with happiness deep

Craighalky, Knocklochy, and Ailnaic so steep,

The clear winding Avon, the fair Ellan-no,

The birk-covered braes that surround Delnabo.

Strathavon, farewell! though I cannot remain, Strathavon farewell for I cannot remain

I trust that they vale I may visit again; Your glen I hope to visit again

How that will delight me, words fail me to tell, How that will delight me words fail to tell

And soon may the day come - Strathavon, farewell! But hasten the day. Tomintoul now farewell!

It is not clear if Rose wrote several versions at different times. The poem may be part of an established local folk tradition of farewell songs or he may have started a fashion for them. Perhaps someone may know and be kind enough to tell us.

Rose worked his way around the States and eventually found a new career in journalism under his self-chosen name A.M.R.Gordon

Writing from San Francisco in 1887 he explained his change of name:

“I made a slight change in my name when I took to journalism and gave up the ministry. I was ashamed of the change at the time (change of profession I mean), and I could not bear that my name should appear in it [the newspaper]. I was in the depths besides, and hoped that nobody would ever hear from or of me again. I feel very different now but the thing is done and cannot be undone”.

It seems likely that the choice of Gordon came to him because of his admiration for and desire to emulate the Gordons of Croughly and also of St Bridget.

He remained a drifter however.

In the same letter of 1877 he summed up his travels to date:

“I have had a wonderful experience, or rather, series of experiences, since I landed in America. I have, as you see, crossed the continent - not in a jump, but step by step, as it were. At one time editing a paper. At another out on the prairie for four months, four hundred miles from the nearest house, and right at the base of the Rocky Mountains, which I afterwards crossed in a Pullman car. For a couple of weeks I looked up the Mormons in Salt Lake City. For a couple of years I edited three papers (Dailies) in Washingston territory; for eight months I was a reporter in Victoria, Vancouver Island. I penetrated to the headwaters of the Fraser River. I have now been nearly four years in San Francisco, sporting editor of the two leading dailies here - a considerable change, you will admit from the quiet life in Evie”.

Dey says that he continued to live and work in California for a further seven years after that.

By June 1895 however he had met the painter and engraver, John Innes, and was writing for The Canadian Magazine about a competitive fishing trip up at Yuba Dam, which he had won using techniques learned as a boy at Faebuie by Loch Avon, “for was it not on such streams and among such hills that I had learned to lure the trout from foaming, rapid, and swirling pools, far away among the bens and glens of ‘Bonnie Scotland’”.

Dey not only collected some of Rose's verses but also knew of some of his journalistic contributions. He particularly cites an amusing article that appeared in the same magazine in July that year called “Bernhardt and the Bear”.

Much of the humour is lost on us now but it is based on a real incident but grossly distorted for a dig at journalistic scoops and fake news.

Sarah Bernhardt, a French actress, though mostly remembered as a Shakespearean tragedienne, was perhaps the most idolized actress ever. She gained the title of “the divine”. Her private life , to which Greeg hints in his story, was perhaps most suited to that of a Greek divinity. She visited Seattle in regal style in 1891, arriving there in a 12 car [carriage] train. Three Pullman ones, two private carriages, and one which was like a palace on wheels in which she, herelf, travelled. In addition there was also one day coach, plus five baggage cars and the engine.

She was invited to a hunt whilst there beside Green Lake in Woodland Park owned by Guy Phinney.

The hunt was unsuccessful but the picnic and day out was enjoyed thoroughly by all.

For reasons that we cannot now know Rose uses this incident to lampoon the key characters in the story and to undermine the notion that we should believe all that appears in print. The story of the quick change of outfit for a hunt of some kind is said to be authentic but the tame bear is pure invention perhaps based on the fact that a menagerie was also established in the park. The racist innuendo would certainly not pass in a modern journal but was of its time. This story is available here thanks to Toronto University and Internet Archive.

..........

THE BERNHARDT AND THE BEAR.

How the Celebrated Actress Shot a Bear.

BY. A. M. R. GORDON.

A LITTLE over five years ago, the city of Seattle was honored with a visit by “ the Divine Sara ” Bernhardt.

The great actress, to be sure, did not patronize any of the fine hotels which the city boasted. She had her own car [carriage], side-tracked at the depot, and lived and moved and had her being therein during the most of the time when she was not on the boards in the Opera House… She was not seen to any extent on the sidewalks of Seattle’s leading streets. She kept herself to herself, except so far she may have talked to Manager Abbey, [Henry E. Abbey] and her cher garcon Maurice, whose surname, for reasons, is the same as that of his maman.

To newspaper interviewers, she was absolutely invisible, and the “sleuths” of the press tried vainly all manner of devices to get a word with the great actress.

There was one scribe, however, who accomplished what every one believed to be the impossible. He succeeded, not indeed in interviewing the Bernhardt in the sense of getting a confidential “talk” with her, but seeing her kill a bear, by planting a bullet squarely between its eyes, and thus beholding her in a new role — one certainly never filled by her on any stage.

This is how it came about.

Guy C. Phinney, a very successful and most genial real estate man of Seattle, had laid out, in the suburbs, a fine place of resort which he had named “Woodland Park.” He had built a trolley road to it; had cleared and laid out a part of it in the most approved “park” style, but by far the larger portion of it still remained in the condition which Longfellow has defined, for all time, as “the forest primeval.”

Mr. Phinney had, through the columns of the local press, from time to time circulated reports that a bear or bears had been seen there, but few, if any, of the people of Seattle believed the stories, and these attemps to add fierce nature to the other charms of Woodland Park seemed destined to end in smoke, to the disappointment of Mr. Phinney and his discredit as an ingenious advertiser.

But if any man thought that Phinney was to be “left” when it came to advertising, that man was fooled. Sara Bernhardt’s arrival gave him the very chance Mr. Phinney was waiting for.

He buttonholed Abbey on the evening when Madame Bernhardt was going to play, and told him that, if “the divine” would like to get some bear-shooting in the immediate neighborhood of the city, he would be delighted to accommodate her in his demesne of Woodland Park on the following day.

On Mr. Abbey’s broaching the idea to the Bernhardt, that lady literally jumped at it, and arrangements were promptly made that the hunting party should proceed to the park the following day.

Mr. Phinney had now to find the bear.

This there was little or no difficulty in doing. A histogenetic (whatever that may mean) doctor in the city had a tame black bear which he was willing to dispose of for the sum of $100. Phinney promptly bought the animal, and arranged for his conveyance to Woodland Park on the following morning, under the care of the Chinese factotum doctor.

The arrangement was duly carried out, so far as starting the Chinaman and his charge along the road was concerned. But trouble began en route. Bruin took the idea into his head that he might vary the monotony of trudging along the dusty road by “climbing” his Mongolian leader, and the latter incontinently fled, leaving the bear to his own devices.

When Phinney heard of this he immediately organized a band of men to recapture the bear, for he felt “in his bones” that it would never do to have Madame Bernhardt "draw a blank” in Woodland Park.

The bear was finally caught, released from his chains, and comfortably "treed” in the shadiest and wildest part of the park.

Then Mr. Phinney notified the favored reporter aforesaid (he worked on an evening paper) and in due time the latter followed up the carriage containing Mdme. Bernhardt, Maurice Bernhardt, Mr. Abbey, and Guy Phinney, in the direction of Woodland Park.

Arrived at the gateway, all left the carriage, and Mdme. Bernhardt, excusing herself for a minute or two, stepped behind the vehicle and returned without her petticoats and skirt, and clad in the bifurcated garb of the French huntsman, breeches, top-boots, and all en regie. In her hand she carried a dainty rifle, and looked “business” all over.

There was no time lost in reaching the foot of the tree where the bear was, though Phinney made a great show of hunting around with two mongrel hounds which he had impressed into his service for the day.

When it was announced that the quarry had been located, Mdme. Bernhardt stepped coolly forward, sighted the head of the animal and, with the coolness of one who having long ago got over “stage fright,” took no account of “buck fever,” planted a bullet straight between the eyes of bruin, and tumbled him to the foot of the tree as dead as Queen Anne.

He was a big, “well-nourished ” bear — a proof of the soundness of the histogenetic system of treatment, and as the great tragedienne with stately grace planted her foot on his body it was a tableux worth a good deal to see.

The scribe returned to his office, wrote the whole story for his paper as a bona fide bear-hunt, and it “went” with the public.

The morning papers were “left” — “scooped.” They had had no reporter on the ground, and all they could do was to re-hash the story told by the evening journal. Of course, nothing could be got out of Mr. Phinney but what was confirmation of the evening paper’s story, and Abbey did not know anything more than what he had seen. So the morning papers confirmed the tale. “The Divine Sara” left next day under the impression that she had, in very truth, slain a wild bear, and the eastern press reprinted the story.

.................

In a magazine called Home and Youth in 1898 (not yet traced) Rose also wrote “Where the Grey Wolf Haunts”. In it an old trapper called, Jim Grew, delivers a sermon on skates for a budding minister called Melville. Dey says “The young man was fond of airing his crude theology, in season and out of season, and the old man showed him that fancy skating, like pulpit theological dissertation, would be of little use, when it were a matter of life and death, to escape either the grey wolf or the great enemy’s clutches”.

Rose's/Gordon's journalistic career has not been fully researched but it is known that he contributed amongst other papers to the San Diego Daily Bee and the San Fransisco Sunday Chronicle and The Daily Call.

Still "The Greeg" could not find peace. Near the end of his life he explains his struggle though not its cause: “I simply could not remain in one place, and I have wandered nearly all over the North American Continent, from Quebec to Vancouver and from Mexico to Alaska”.

The following year from July 1st to October 2nd he wrote all the copy for a comic newspaper Ye Hornet with illustrations by John Innes, best known now as the “painter of the Canadian West”. The two men shared a restless search for identity and lasting significance. Some of Innes' family may also have originated in this area though he was born in Canada so that perhaps they also shared a common heritage.

Whatever may be the truth about Rose’s excessive drinking in Orkney, alcohol certainly features in most of the verses and quite a lot of the prose he wrote in the first issue.

All the 14 issues can be found on http://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04256

One of the more telling verses, however, set to the tune “Castles in the Air” is not about alcoholism at all but about the folly of human pretence. It concerns a "canny, canny rogue” who cheated people by selling fake plots of land. When he is eventually rumbled he decides to do exactly what Rose himself had done. He describes his anti-hero trudging along the railway lines swearing about his losses and eventually doing some menial job whilst “probably slinging hash”. Even though this may not have been precisely The Greeg’s own fate it is certainly an indication of the kind of tragic life he came to know intimately on the road.

He was in Toronto in 1895 where he caught typhoid. Then, the following year he tramped on foot from there to Montreal where he joined The Gazette moving on from there to The Montreal Herald.

The Montreal Herald, the first daily paper in Montreal, was founded by Mungo Ray but gained its readership and character under the second owner and editor William Grey. He had originally come from Huntly. The paper's biases were Presbyterian religiously and Whig politically. Its stated aims were to produce “interesting, useful and gratifying information” but also to offer a platform for the talents of “Gentlemen whose talents and leisure may enable them to favor..[the newspaper] with…productions… in the English language”

In 1898 Rose wrote his last letter to Mr Anderson in Aberdeen making enquiries about his family but by this time his health was so damaged by his life style that he had a stroke and was taken by his friends to Notre Dame Hospital where he finally died. Only after this did his friends in Canada find out that he had left a wife and two sons in Scotland.

His hospital costs and burial were taken care of by two charitable gentlemen, William Drysdale and Norman Murray so that he was finally laid to rest in Mount Royal Cemetery.

His deepest longings, about which he had written so many years before, were at last to be fulfilled.

The Gane Awa’ Land (from The Canadian Monthly October 1880)

Oh! Fair is the “land o’ the Gane awa’’,

Fairer than eye o’ Earth-born saw

Till he’d passed through the gates o’ the living and dead.

There is rest in the “Land o’ the Gane awa’”.

Nae storms beat there, nae cauld winds blaw,

But the tired han’ rests and the thocht-rackt head,

And the ingathered flocks nae disturber dread,

For the wings o’ our God are above them spread.

There’s fading nae mair wi’ the “Gane awa”,

The bluims o’ Eternity ever blaw

In the blissfu’ God-keept garden there;

Nor shadow nor cloud in the clear blue lift,

And heaven’s saft breezes ken nae shift;

A rippleless calm is its sea evermair,

Nae billow of trouble nor toil nor care

Breaks on the shores of that Land so fair.

Oh! would I were there wi’ the “Gane awa”,

For the shadows o’ even begin to fa’

And the warld is lanesome as it can be,

When a’ that I lo’ed frae me are awa’

The wife o’ my heart and her bairnies twa-

In the “Gane awa’ Land” them a’ I’ll see,

And blithe will ooor meetin’ and greetin’ be,

To live evermair whar’ they never dee,

In our Father’s Home in Eternity.”

Acknowledgements: Sarah Maclean, Orkney Library & Archive, Kirkwall particularly for her painstaking transcription of one of the newspaper articles that was unreadable in the scan.

http://www.orkneylibrary.org.uk/

http://orkneyarchive.blogspot.co.uk/

Further Resources for anyone interested in follow up:

There is, to my knowledge, no specific collection of records (fonds) relating to Alexander M. Rose/A.M.R. Gordon in any Canadian or Scottish University at present. I would be delighted to be proved wrong.

The letters to P.J. Anderson have not been traced by me. They would obviously be a valuable primary source. I am assuming that this is the P.J. Anderson who was the librarian at the Unversity of Aberdeen whom Rose would have met whilst studying divinity there between 1871 and 1875 when P.J.Anderson was also a student. This may be a false assumption but perhaps someone can provide the answers and point to an archive.

There are , however, scattered resources on line. The link to Ye Hornet is given in the main txt.

archive.org is well worth searching, as always, for A. MacGregor Rose texts though some are also available in reprints. To get the flavour of the times I suggest you try to access the versions of some of the Canadian verses with their illustrations though Dey has included all the major verse texts. Hoc der Kaiser was illustrated by Jessie A. Walker for example and the Laurier poems by John Innes.

Whit Cunliffe (1876-1966) an English comic singer usually remembered for the outfits worn during his Music Hall appearances made the song "Hoch, Hoch Der Kaiser” popular as part of the early war effort. This is likely to be the version set to music by George Brinkerhoff to be found in The Library of Congress

A short animation in black and white of Hoc Der Kaiser was produced by The Universal Film Manufacturing Company. Cf IMDbPro (Not seen by me)

Whilst much of this has more historical interest than current value it helps us understand the times in both Scotland Canada just a little better.