NORTHERN SKIES | sitemap | log in NORTHERN SKIES | sitemap | log in

|

|

||

| This is a free Spanglefish 1 website. | ||

COMETSFor a continueation please go temporary page: COMET TWO.

2014 January 11. 2014 January 11. Early morning observations of comets Lovejoy & LINEAR, initially in a sky of moderately good transparency and seeing but with considerable cloud cover driven by a strong, cold NE wind. C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 2014 January 11, 05h 13m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 40 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (2° x 1°.5) is TYC 1552-2175-1 mag: 9.21. (Left click to enlarge image.) Comet’s data at time of observation: Right Ascension: 17h 46m 35.3s Declination: +15° 30' 42" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 23° 34' Azimuth: 99° 13' Hour angle: 19h 20m 23s Rise: 2h 36m 23s Transit: 10h 32m 0s Set: 18h 25m 20s Distance: 1.2489 AU (186.8 million km) Radius vector: 0.8918 AU (133.4 million km) Horizontal parallax: 7.04" Comet LINEAR C2012 X1 (LINEAR) imaged 2014 January 11 at 05h 48m UT. Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 40 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. Cropped image: the brightest star in the field (dia. 50' approx.) is the long period variable star kappa Ophiuchi, mag. 5.0 to 4.1 spectral class K2IIIvar. (Left click to enlarge image.) Comet’s positional data at time of observation: Right Ascension: 17h 0m 36.1s Declination: +9° 2' 37" Constellation: Ophiuchus Altitude: 23° 38' Azimuth: 113° 22' Hour angle: 20h 6m 22s Rise: 2h 39m 58s Transit: 9h 46m 21s Set: 16h 51m 54s Elongation: 48.0° Distance: 2.1858 AU (327.0 million km) Radius vector: 1.6933 AU (253.3 million km) Horizontal parallax: 4.02"

2014 January 06. 2014 January 05. Early morning observations of comets Lovejoy and LINEAR, initially in a sky of moderately good transparency and seeing, this time with better conditions in the e sky allowing observations over a period of an hour on both comets. Artificial Earth satellites (AES) were a significant problem with 1 in 3 frames being “infested”. C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 2014 January 06, 05h 09m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 50 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (2° x 1°.5) is TYC 1542-1043-1 mag. 7.72 spectral class A0. (Left click to enlarge image.) Comet’s data for 05h 09m UT. Right Ascension: 17h 38m 30.2s Declination: +17° 44' 34" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 18° 22' Azimuth: 85° 53' Hour angle: 18h 24m 47s Rise: 2h 28m 56s Transit: 10h 43m 42s Set: 18h 55m 41s Elongation: 45.9° Distance: 1.1710 AU (175.2 million km) Radius vector: 0.8571 AU (128.2 million km) Horizontal parallax: 7.51" The two cropped images (dia. 1° approx.) from exposures a little under one hour apart indicate not only the movement of the comet in that period against the stellar background but also the apparent alteration in star colours tending to “redden” at the lower altitude due to the great thickness of the Earth’s atmosphere through which the light path has to travel as well as variation in atmospheric transparency between the two observations.

C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 2014 January 06, 04h 47m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 55 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200.

C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 2014 January 06, 05h 41m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 55 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. C2012 X1 (LINEAR). This comet requires a longer focal length instrument to show any detail. With limited time, and rapidly changing weather patterns, to change instruments was deemed impracticable. We therefore had to make do with 600mm f.l.! C2012 X1 (LINEAR) imaged 2014 January 01 at 04h 51m UT. Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 45 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. Cropped image: the brightest star in the field (dia. 50' approx.) is STF 2090 mag 7.88 spectral class K5. (Left click to enlarge image.) Comet’s positional data at time of observation: Right Ascension: 16h 45m 18.7s Declination: +10° 2' 2" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 18° 35' Azimuth: 101° 43' Hour angle: 19h 17m 58s Rise: 2h 37m 21s Transit: 9h 50m 52s Set: 17h 3m 30s Elongation: 47.9° Distance: 2.2140 AU (331.2 million km) Radius vector: 1.7165 AU (256.8 million km) Horizontal parallax: 3.97"

2014 January 05. Early morning observations of comets Lovejoy and LINEAR, initially in a sky of moderately good transparency and seeing, but again clouding over in the S/E by 05h 30m UT. In other words, another exercise in cloud dodging in which Lovejoy came off well but LINEAR evaded observation in any meaningful sense. As I say, you have to be extremely dedicated or plain mad to pursue this sort of thing from this location, and at this hour of the day! Despite all the frustration, a series of fine images (considering the low altitude) for Comet Lovejoy were secured with the Nikkor 600mm f/4 and D300 SLR commencing 04h 32m UT and concluding with the image below at 05h 05m UT. C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 2014 January 05, 05h 05m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 45 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (2° x 1°.5) is TYC 1546-208-1, mag. 5.65 spectral class F6V. One of the best images from a longer exposure was marred by the appearance of an artificial Earth satellite (AES), a risk one always has to take with these longer exposures nowadays since the sky is now cluttered with the damn things: see below.

C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 2014 January 05, 05h 05m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 65 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. Cropped image with AES crossing the field in the lower left-hand corner. Comet’s data for 05h 05m UT. Right Ascension: 17h 36m 45.9s Declination: +18° 12' 31" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 17° 58' Azimuth: 84° 18' Hour angle: 18h 18m 33s Rise: 2h 26m 57s Transit: 10h 45m 55s Set: 19h 1m 59s Elongation: 46.1° Distance: 1.1545 AU (172.7 million km) Radius vector: 0.8512 AU (127.3 million km) Horizontal parallax: 7.62" — 2014 Janaury 01. Early morning observations of comets Lovejoy and LINEAR in a sky of moderately good transparency and seeing, clouding over after 05h 30m UT. Wind S: force 4 – 5. The two images below display the comet’s movement against the stellar background over a period of 43 minutes. C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 04h 39m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 50 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (2° x 1°.5) is TYC 1545-2527-1 mag. 5.52 spectral class B5V. 2014 January 01. C2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Imaged 05h 22m UT, Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 50 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 1200. (Left click to enlarge images.) Comet’s data for 05h 22m UT. Right Ascension: 17h 29m 20.1s Declination: +20° 8' 7" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 20° 45' Azimuth: 85° 8' Hour angle: 18h 27m 42s Rise: 2h 16m 53s Transit: 10h 54m 17s Set: 19h 28m 11s Elongation: 47.1° Distance: 1.0860 AU (162.5 million km) Radius vector: 0.8317 AU (124.4 million km) Horizontal parallax: 8.10" C2012 X1 (LINEAR)

C2012 X1 (LINEAR) imaged 2014 January 01 at 04h 51m UT. Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 45 sec. exposure D800 SLR ISO 1200. Cropped image: the brightest star in the field (65' x 40' approx.) The brightest star in the field (45' x 45' approx.) is TYC 964-337-1 mag. 9.06, spectral class F8. Comet’s positional data at time of observation: Right Ascension: 16h 30m 1.7s Declination: +11° 1' 58" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 16° 37' Azimuth: 96° 15' Hour angle: 18h 55m 38s Rise: 2h 34m 29s Transit: 9h 55m 20s Set: 17h 15m 16s Comet’s geometric data: Elongation: 47.7° Distance: 2.2448 AU (335.8 million km) Radius vector: 1.7418 AU (260.6 million km) Horizontal parallax: 3.92" 2013 December 31. 2013: "The Year of The COMET" – the grand finale. Observations of Comet Lovejoy et al for the early morning December 31st 2013. With a reasonably clear sky at 04h 00m UT, the possibility for a good early morning observing session looked promising. However, sky clarity became steadily plagued by cirrus, leading to poor visibility before work terminated at around 05h 30m UT. Comet Lovejoy is visibly fading from day to day now, not helped from these latitudes by a steady drop in elevation. To compensate for the diminished apparent angular size, and with a break in the sky of an hour or more, it was decided to use the 600mm f/4 lens with longer exposures (anything above 60 sec. gave sky glow) in addition to the 400mm f/2.8.

A final search using the fast, wide angle 200mm f/2 lens for fragments from Comet ISON, which might be expected at high elevations in the region of Ursa Minor, revealed nothing.

Frames for Comet Lovejoy are given using all three lenses commencing with the 200mm f/2 and therefore not in strict time sequence. (Left click button to enlarge each of the three frames.) 2013 December 31. A "wide" field view using a Nikkor 200mm f/2. A 10 sec. exposure at 05h 32m UT. D800 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (6°x4°) is delta Herculis mag. 3.12 spectral class: A3IVv SB. Poor clarity causing “fogging” of images and general background sky illumination at this altitude. 2013 December 31. Nikkor 400mm f/2.8, a 30 sec. exposure at 04h 59m UT. D800 SLR ISO 1200. Field 3°.4 x 2°.4. Falling quality in sky transparency giving rise to background sky illumination at this altitude. 2013 December 31. Nikkor 600mm f/4, a 50 sec. exposure at 05h 19m UT. D800 SLR ISO 1200. Field 2°.0 x 1°.5. Comet’s local positional data for this observation: Right Ascension: 17h 27m 19.1s Declination: +20° 38' 19" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 20° 5' Azimuth: 83° 3' Hour angle: 18h 19m 12s Rise: 2h 17m 9s Transit: 10h 59m 34s Set: 19h 38m 19s Geometric data: Elongation: 47.4° Distance: 1.0681 AU (159.8 million km) Radius vector: 0.8278 AU (123.8 million km) Horizontal parallax: 8.23" Comet LINEAR :

C2012 X1 (LINEAR) imaged 2013 December 31 at 05h 09m UT. Nikkor 600mm f/4. A 50 sec. exposure D800 SLR ISO 1200. Cropped image: the brightest star in the field (65' x 40' approx.) is TYC 967-1559-1 mag. 6.11 spectral class G8III. Stars to magnitude 16.5 are readily discernable on high resolution images. The comet would appear to be showing some indication of the extended coma picked up easily in the observations of 2013 November 10. Comet’s positional data at time of observation: Right Ascension: 16h 26m 59.7s Declination: +11° 13' 56" Constellation: Hercules Altitude: 17° 42' Azimuth: 97° 42' Hour angle: 19h 2m 44s Rise: 2h 33m 53s Transit: 9h 56m 13s Set: 17h 17m 38s Comet’s geometric data: Elongation: 47.7° Distance: 2.2512 AU (336.8 million km) Radius vector: 1.7471 AU (261.4 million km) Horizontal parallax: 3.91"

2013 December 29: Comets Lovejoy & LINEAR. 2013 December 29. Comet Lovejoy imaged at 05h 08m UT. Nikkor 400mm f/2.8. A 30 sec exposure, D800 SLR, ISO 1200. Sky almost completely cloud covered with gentle rain falling! The brightest star in the field (2°.4 x 1°.8 approx.) is 73 Herculis, mag. 5.70, spectral class: F0IV. Local data for comet at time of observation: Geometric data: The comet was well seen at 05h 10m UT in 8x30 binoculars before the sky completely clouded over. Impressive in 20x80s. Note: Comet C2012 X1 (LINEAR) appears to have brightened a little.

C2012 X1 (LINEAR) imaged 2013 December 29 at 05h 02m UT. Nikkor 400mm F/2.8, a 35 sec. exposure D800 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (1°.5 x 0°.75 approx. ) is TYC 967-1376-1 mag. 8.11, class K0. Local data for comet at time of observation: Right Ascension: 16h 20m 54.8s Geometric data: Elongation: 47.6° 2013 December 26: Comet C/2013 R1 Lovejoy. The comet continues to image well despite having lost declination making it no longer circumpolar from the latitude of Orkney. The image this evening was taken with some residual twilight and worsening atmospheric clarity. Although visible in the morning sky, the Moon’s presence will deter observations of the comet for a day or so yet. Comet C/2013 R1 Lovejoy 2013 December 26, imaged 17h29m UT. A 20 sec. exposure, Nikkor 400mm f/2.8. D800 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (2°x1° approx.) is delta Herculis mag. 3.12, spectral class: A3IVv SB. Despite residual twilight, stars to mag. 15 are clearly visible.

Geometric data:

2013 December 14. Comet Roundup. The night and early morning of December 13/14 proved to be a mixture of clear intervals between batches of dense cumulus. The Moon was the chief obstacle to securing images of Comet Lovejoy in the early stages. We were also hoping to make an attempt on searching for remnants of Comet ISON as well as the fading Comet Linear, this only being possible after moonset (05h 30m UT) and before twilight set in on the morning of the 14th. We were all set up by 04h 30m UT on the morning of the 14th by which time much of the sky was covered in cloud. However, the Geminid meteor shower scheduled to peak at around 01h UT on the same morning was showing considerable activity and once the sky cleared again (and despite the presence of the Moon) we made a count of well over one meteor per minute, with some very bright ones rivaling Jupiter in brilliance It was decided to use the fast 400mm f/2.8 Nikkor lens coupled to the D300 SLR. Ideally we would have switched later to the 600mm f/4 had conditions permitted but decided, instead, upon extending the focal length of the 400mm to 800mm with a x2 converter for the much “smaller” Comet LINEAR. We commenced imaging at 04h 40m with shorter exposures due to moonlight. After moonset we were able to extend exposures to 60 secs. (for LINEAR); 25 secs. proved to be the optimum for Lovejoy. Despite the use of exposures up to 40 secs in the region where remnants of comet ISON might be expected, nothing was found. The three frames below show clearly the apparent movement of Comet Lovejoy against the star background as it makes towards the star TYC 2581-1822-1 mag. 8.79. The angular movement in this period is 7' 08", or a little under 1/4 of the Moon's apparent diameter.

2013 December 14, 04h 45m UT

2013 December 14, 05h 34m UT 2013 December 14, 06h 31m UT (Left click to enlarge.) The Brightest star in all fields (3.4° x 2.4° approx.) is BU 818 mag. 6.87 Spectral class F0III. Nikkor 400mm f/2.8, D300 SLR ISO 1200. Exposure 25 sec. There is some evidence of wind shake in the first image which was taken when the Moon was still in evidence and lighting the sky background. This morning will be the last opportunity to image Lovejoy in a dark sky for some 17days by which time its declination and altitude will have decreased, along with a general fading as aresult of the comet's increasing distance from Earth and the Sun. Comet Lovejoy data at December 14, 05h 00m UT: Distance: 0.7369 AU (110.2 million km) Right Ascension: 16h 35m 54s 2013 December 09: C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy). 2013 December 09. Comet Lovejoy imaged at 18h 48m UT. Nikkor 400mm f/2.8. D300 SLR, 18 sec. exp. ISO1200. (Left click to enlarge.) The Brightest star in the field (3.4° x 2.4° approx.) is the variable star TZ Coronae Borealis, Maximum mag. 5.69 (Magnitude range: 0.05) Spectral class: F8V. Comet: Positional information at observation. Elongation: 58.3° Right Ascension: 16h 11m 34 Moon: Phase 51.8% Constellation: Pisces Weather poor with thin cloud and sky background light from Moon.

Heavily processed image from the above. Magnitude limit approcimately 16.5. 2013 December 04: C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy). Comet Lovejoy: 2013 December 04, 05h 04m UT. Nikkor 400mm f/2.8, exp. 20 sec. D300 SLR, ISO 1200. (Left click to enlarge.) The bright star in the field is mu1 Bootis, mag. 4.31 Spectral class F0V. Some “fogging” due to thin cloud. Poor weather with sky overcastting quickly. 2013 December 03: C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy). 2013 December 03, 19h 36m. Nikkor 400mm f/2.8. A 40 sec. exposure. D300 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (3.4° x 2.3°) is TYC 3052-2052-1 mag.5.56 Spectral class: K4III. (Left click to enlarge.) Positional data for time of observation: Right Ascension: 15h 22m 58s Distance: 0.5381 AU (80.5 million km) Note: this is a good quality image in view of the comet‘s low altitude. An artificial Earth satellite is an unwelcome addition! Just visible to the uanaided eye, fine in 8x40 binoculars. 2013 December 02. Re: Comet ISON. We have just received (20h UT) the following bulletin from the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association: “Sadly the comet appears not to have survived its ordeal after all. It steadily faded and became more diffuse after its initial reappearance. Something might be visible as the remnant moves into darker skies, but this is likely to require deep imaging.” Readers will know from experience that we generally comment on the actual appearance of an object only after we have made observations of our own. We have no reason to doubt the comet’s demise viewed as a “spectacular”. However, we would hope to secure some images within the coming week/s, weather permitting,. And on that score let it be said that the recent month has been the most disappointing in our observing career: not a twinkle for over three weeks! JCV 2013 November 23: Three Comets Update. Only Comet Lovejoy is currently observable from the latitude of Orkney with anything approaching ease. Comet ISON is now out of reach as it closes in on the Sun. We have yet to receive an update on its recent performance. Whether it will survive this close encounter with the Sun remains to be seen. Comet LINEAR is fading fast but would be observable in small telescopes in a dark, clear sky. Comet Lovejoy is at present a spectacular photographic object, as may be seen from the image below. Early morning observations of Comets Lovejoy & LINEAR in twilight and Moon at phase 73.3% in constellation Cancer and just 60° apparent separation from the comet. Comet LINEAR, close to the brilliant star Arcturus, was imaged but only recorded as a very faint object against a brightly lit sky background from both twilight and the Moon.

Comet LOVEJOY. 2013 November 23, 06h 47m UT. A 6 sec. exposure 150mm f/5 achromatic refractor, D300 ISO 1200. The star closest to the comet is TYC 3020-1723-1, mag. 10.70. (Field 1.4° x 1° approx.) Left click to enlarge. Data for Comet: R.A. 12h 40m 7.7s Magnitude: 5.2 (est.) As will be seen, the comet is circumpolar from the latitude of Orkney and will continue to be so until 16 December. It is also at maximum brilliance at around mag. 5.2, an easy object in small binoculars and just visible to the unaided eye on a clear, dark night.

2013 November 10: Three Comets in the Morning Sky. The trials and tribulations of the observational astronomer. A Provisional Account (full data to follow shortly). Orcadians will not need reminding that the weather recently – in fact for some time – has not been up to much!. Astronomically, in order to get any observational work done at all, one has either to be totally committed and optimistic or just plain crazy or both! I think I must come into the latter category since now well into my seventies my brain drives my body to painful exertions in the hope of getting a glimpse or two of the celestial sky at night. Sample the morning of November 10. On the agenda are three comets, two of which (LINEAR & ISON) can only be tracked from these latitudes from around 04h 30m UT. The third, (LOVEJOY), has a good altitude by this time – see below. Awakening instinctively at 03h 45m before the alarm clock sounds off, one hastens out of bed to the east facing window. Not much to get excited about. Leo paying host to planet Mars spattered with cloud. The north window gives a more encouraging picture and so to the bathroom (cold since the heater has not had time to make any impression), dressed in three minutes. A further layer of clothing to combat the outside cold: boots, and thence to the observing stand in order to set up the equipment. The sky looks very fine in parts but the cloud forms and disperses before you can say damn, but never the less one presses ahead. It takes some four to five minutes to have things ready for a first shot at one of the three comets we hope to capture digitally using a fast, heavy Nikkor 400mm f/2.8 lens coupled to a D300 SLR. The first comet to tackle is Lovejoy, now at a good altitude on the border between constellations Cancer and Leo. A 10 second exposure shows the comet off well. Next the tedious business of adjusting the lens focus using slightly faster speeds at various settings on the vernier. (These lenses have helical focusing so we have attached verniers to give greater refinement. This is necessary since with these long-focus lenses focus to infinity will vary with the air temperature. ) That done, the serious business of imaging the comets may commence. However, the weather has other ideas so that the sky has now become almost completely overcast. The telescope mounting and handset have been set the previous evening to give positions for the three comets at 04h 00m UT. (Note that all three are moving at a prodigious rate against the stellar background necessitating positional settings at approximately hourly intervals.) The only portion of sky offering a hope of seeing anything is in the region of constellation Bootes so thence we track in order to attempt a go at Comet LINEAR. The altitude is low and wisps of cloud make the first exposure a compromise; never the less, the comet is “there”. Now cloud forms here and we track back to Comet Lovejoy where the sky is clean, thereby offering a few minutes in which to take a series of images all of which come out well. Comet ISON is now at –2° declination and not well placed at a low altitude where cloud sits persistently. Shot after shot with the camera reveals a blank screen until, just for a few seconds, we have confirmation that the comet is indeed “there”. Meantime, the sky has improved in the direction NNE, so back to LINEAR. Just time for a “quick one”, and it’s back to ISON where during the course some twenty minutes one waits patiently in order to secure just one image of the comet sandwiched between two banks of cloud. On a point of technique: ideally one world use set exposures possible between 10 and 30 seconds but owing to the erratic behaviour from cloud it is best to have control of the exposure so as to curtail things on the instant. This requires a “bulb” shutter setting and for one to monitor the sky situation carefully throughout the exposure. We have been at it now for a little under one-and-half hours and the sky is beginning to light up with the coming of dawn. The sky is now almost totally cloud covered and so we abandon any further attempts to secure good images of LINEAR and ISON. Stowing the equipment back indoors takes under five minutes. All one has to do now is to take a quick look at the results and then to warm the body up before returning to bed for a few hours sleep – if you are lucky!

C2013 R1 (Lovejoy)

C2012 S1 (ISON)

C2012 K5 (LINEAR) JCV 2013 November 10, 06h 00m UT

2013 November 07: C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy). 2013 November 07: late night observations of C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy). This is the first observations we have been able to make of this comet which has brightened to around mag. 6.5 (a little below unaided-eye visibility) considerably above predicted levels. The comet is brightening as it hastens east, gaining in declination and brightness up to 25 November (see chart below). The rate of apparent movement of the comet may be gauged by reference to the nearby star in the two images below. In view of the speed at which the comet is moving against the sidereal rate, we used the fast 400mm f/2.8 lens with exposures between 15 sec. and 30 sec. A wide field view from a 4 sec. exposure on the Nikkor 105 f/1.8 shows the comet in relation to the “Beehive Cluster” in Cancer. The brightest star in the field (dia, 8° approx.) is delta Cancri mag. 3.93. The comet is shown between the two, vertical white lines.D100 SLR: static camera.

2013 November 07, 22h 24m UT. A 25 sec. exposure: Nikkor 400mm f/2.8 D300 SLR ISO 1600. The brightest star the field (dia, 1.4° approx.) is TYC 1396-794-1 mag. 7.72.

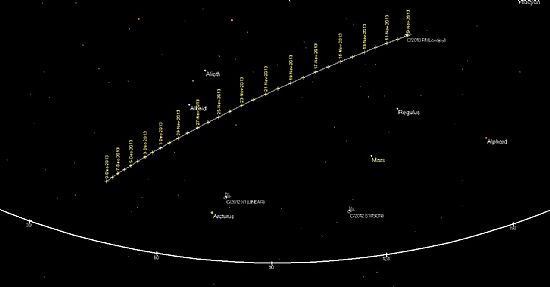

2013 November 07, 23h 17m UT. A 20 sec. exposure: Nikkor 400mm f/2.8 D300 SLR ISO 1600. The images are reasonable considering the ,low altitude of the comet at the time of observation. Comet data (positional only): Constellation: Cancer Track of C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy) against stellar background 2013 November 09 to December 09. Left click to enlarge. 2013 November 02; Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) Poor conditions with light cloud and rain on and off leading to complete overcastting within 30 minutes of commencement of observations.

2013 November 06, 04h 42m UT. Nikkor 600mm f/4, D800 SLR ISO 1200. A 25 sec. exposure Comet’s mag. 7.1 (est.) tail 22' approx. Brightest star in field ( 1.8° approx.) TYC 272-406-1 mag. 6.94 NOTE: Searches for comets C2013 R1 (Lovejoy) and C2012 X1 (LINEAR) gave negative results - CLOUD! 2013 November 02; Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) Another very brief period of early morning clear sky lasting a little under 40 minutes. Slack southerly wind, moderate transparency and good seeing. Used the Nikkor 600mm f/4 with a D800 SLR. Exposures above 30 secs. tended to “fog” from sky illumination. 2013 November 02, 05h 08m UT. A 32 sec. exposure Nikkor 600mm f/4 with a D800 SLR ISO 1200. (Cropped image.) Left click to enlarge. Bightest star in field (dia. 1.0°) is TYC 269-843-1 mag: 8.83. (faintest stars 16 mag.). Integrated mag. 9.4 (est.); tail: 11 arc-minutes (est.). On high resolution images the tail extends to 31 arc-minutes. The galaxy PGC 34783, mag. 15.1 (size: 44.0"x42.0”), is also clearly discernable. 2013 November 02, 05h 07m UT. A 35 sec. exposure Nikkor 600mm f/4 with a D800 SLR ISO 1200. (Cropped image 50'x50' approx.) Left click to enlarge. Comet data: Elongation: 51.4° Right Ascension: 11h 19m 30.0s 2013 October 31; Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) Observations commencing 05h 17m UT. 150mm f/5 . achromatic refractor D800 SLR ISO 1200. This image, restricted to 30 sec. due to the nearby crescent Moon (phase 12.8%). The comet has increased in apparent brightness to an estimated integrated magnitude of 9.6; tail 14 arc-min. The brightest star in field (dia. 1.3° ) is TYC 268-468-1, mag: 7.74 spectral class: K2. Moon at 05h 17m UT: Right ascension: 11h 41m 57.84s Comet data: Integrated magnitude: 9.6 (estimated)

2013 October 27 Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON). Comet ISON imaged 2013 October 27 at 04h 04m UT.150mm f/5 achromatic refractor. A 40 sec. exposure, D800 SLR ISO 1200. The brightest star in the field (1.2° approx.) is TYC 846-277-1 Very poor transparency with Moon (phase 48.4%) close by in Cancer: Right ascension: 08h 29m Comet data: Constellation: Leo

2013 October 14. Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) A very brief let-up in the poor visibily around 04h UT enabling some work to be done on Comet ISON. Little wind with cloud inclined to precipitate “without notice”. Fine naked-eye view of Leo with Mars and Regulus* close to conjunction. (See below): D100 SLR and 24mm f/2.8 Nikkor lens. A 20 sec. exposure (static camera). Again it was decided to use the fast 150mm f/5 aperture achromat., this time using a D800 SLR configured for near maximum resolution and working at ISO 1600. Five reasonable exposures were made at shutter speeds 25 sec. to 45 sec., after which the sky clouded over entirely. The cropped, circular image below shows the comet with the spherical galaxy NGC 3121 (mag. 12.9; 1.7'x1.4') close by to the left. The brightest star in the field (dia. 1.6° approx.) is TYC 836-945-1 mag. 8.97, spectral class M0. Stars to mag. 17, and a number of faint galaxies to mag. 16, are to be seen on high resolution, wider field images.

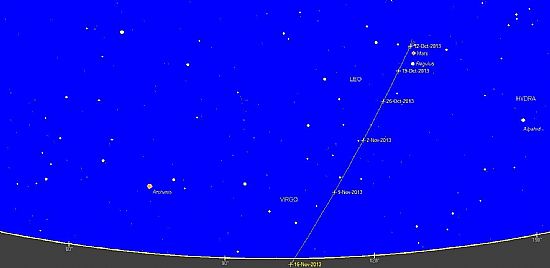

2013 October 14, 04h 26m UT. Comet ISON imaged 150mm f/5 achromatic refractor, a 45 sec. exposure, D800 SLR ISO 1600. (Left click on images to enlarge.) Comet data (14 Oct 2013 04:30): Constellation: Leo Distance: 1.7566 AU (262.8 million km) Preparing for Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) Comet PanSTARRS has left the scene – what next for Comet ISON? Many readers will know that there has been no shortage of speculation as to how this comet might perform towards the close of 2013. Predictions earlier this year that the comet might become a naked eye object in daylight now appear to be fading – literally. Ephemeredes from May last year put the comet’s magnitude at 2013 October 5 at around visual magnitude 10 or a little fainter. Our observations from that date (see below) indicate an apparent magnitude closer to 14 which is around 1/40th of the anticipated brightness back then. ISON is now headed towards the Sun at a distance (at the time of writing) a little under that for planet Mars. As seen in the sky, the two objects appear not far apart. An interesting conjunction with the first magnitude star Regulus occurs on October 15. (See diagram 1 below.) The star and planet will be of around the same apparent brightness but with well contrasting colour, Regulus a white star and Mars appearing orange. Thereafter, the two objects will appear to separate. The position of Mars on 16th November will be close to that occupied by ISON on November the 2nd. The two traces have not been shown on the same diagram (2) to avoid congestion. As mentioned earlier, circumstances for observing the comet from high latitudes are not favourable even supposing the weather should bless us with early morning, clear skies. A chart showing the course of the comet in the sky up to commencement of the observing “blackout period” [Nov. 16 (morning) to Dec. 10 (morning)] is shown in diagram 2. Dia. 2. The Track of Comet ISON from October 12th to November 16th 2013. The sky is shown looking east shortly before sunrise in order to accommodate the tracking data. The comet itself rises on October 12th at 00h 63m UT. and at 04h 25m UT on November 16th. (The later rise time is due to the fall in declination as the comet appears to head south.) Left click to enlarge. Hopeful observers should visit these pages from time to time. We would expect to report on our own observations, indicating when the comet might become visible in binoculars or small telescopes. Maximum brilliance is predicted for November 28th to 30th, but much will depend on how the comet stands up from its close approach to the Sun at that time. A chart update will be given in November to cover the period from Dec. 10. Additional Information. Our problem here in the northern hemisphere is that leading up to maximum brilliance the comet is heading south with its declination on September 1st at +22˚ 08' falling to -22˚ 43' by November 28th , around about the time of maximum brilliance. The comet will be moving rapidly at this time and by December 09 will be back in the northern hemisphere but fading all the time. However, it should still be a naked eye object for the first two weeks in December. We shall publish more precise details over the coming weeks. We are frequently asked to recommend suitable equipment for general astronomical observation and for comets in particular. This is a vast subject in itself for there is no simple answer much depending upon what it is you wish to observe. We shall therefore limit ourselves to comets for the present. For ease of use, and providing you know where to look in the sky, a good pair of 8x40 binoculars can be very useful for comets brighter than visual magnitude 6 or 7. For imaging purposes comets of this magnitude may be captured with a camera mounted on an ordinary tripod using fast aperture lenses (preferably a digital SLR) in a matter of seconds. One of our most useful combinations has proved to be a Nikkor 105mm f/1.8 lens used with a D100 SLR, both of which may be purchased at reasonable prices second-hand. (A 50mm f/1.8 may prove useful for larger comets and this lens would be appreciably cheaper than the 105mm just mentioned.) For those seeking to take up the study of comets a little more seriously, then we would recommend the SkyWatcher 150mm f/5 short focus achromatic refractor. The tube assembly can be purchased for around £400 and may be accommodated on an EQ3* mount for about the same price, including a motor drive. The colour correction is not good and we would not recommend this scope as an all-rounder, but for fast photography where fine colour correction is not essential then you will find this telescope gives a brilliant field with good image quality right up to the edges of the field. *This represents the upper limit for a payload on this mounting. The more expensive EQ5 would be better - it is slightly cheaper than the more sophisticated EQ6, the portable mounting we mostly use here on Rousay. Useful link: http://www.skyandtelescope.com/community/skyblog/observingblog/193909261.html 2013 October 07

2012 October 05. Early morning observation of Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) A slightly better opportunity offered itself this morning with slackening winds (SW force 5 to 6) and longer cloud breaks. However, with the comet relatively low in the eastern sky transparency will always be compromised. Frustrating, to a degree, with an obstinate bank of light cloud “hovering” in front of Leo, but eventually giving way to a period of clarity for half-an hour during which a number of images were obtained using the 150mm achromat. 2013 October 05, 03h 22mm UT. 150mm f/5 achromat. A 45 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 2000. (Left click to enlarge.) The comet at the centre of the field (dia. 50') close to the two stars TYC 1410-772-1 mag. 10.06 (top) TYC 1410-221-1 mag. 10.64, may be seen to have a short tail. The brightest star in the field is TYC 1410-11-1 mag. 8.89 spectral class G5. The faint galaxy GSC 1410-0308 mag. 14.62 may be seen in position 8 ‘o-clock approx. near the edge of the field and seeming to mimic the comet, but without a tail. A number of other fainter galaxies are visible on wider field images where stars to magnitude 17 may be detected. This is a relatively rich area of sky for galaxies since we are looking well away from the galactic plane into what they call “deep sky” in modern speak! Comet’s data: (Constellation: Leo) 2012 October 02. Early morning observation of Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) The first observation of Comet ISON was made from Rousay under extremely exacting conditions at 04h 29m UT. A southerly wind touching gale force at times (force 7 to 8) with considerable cloud giving few breaks for exposures of more than 15 second. Added to this, a growing morning twilight and a nearby crescent Moon (phase 8.8%). It was decided to use the 150mm aperture f/5 achromatic refractor, despite the force of the wind. (Quick location of comet and focusing were essential and this instrument offers a reasonable compromise over the more refined, large Nikkor telephoto lenses.) As it turned out, the weather deteriorated making it possible for only two very short exposures, the first of which was used in the image below. 150mm f/5 achromat. A 30 sec. exposure D300 SLR ISO 2000. (Left click to enlarge.) The comet appears at the centre of the field (dia. 50') slightly below and to the right of the star GSC 1410-0052 mag. 14.30. Indication of a short tail (4')* at 1’clock may be seen on the original high resolution image. Comet estimated magnitude 14.8. Brightest star in the field is TYC 1410-20-1 mag. 7.95 (spectral class: K0). Some distortion of images due to wind “shake”. Comet’s data: (Constellation: Leo) Distance from Earth: 2.1152 AU (316.4 million km)

Forthcoming appearance of Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) in the Northern Hemisphere. Now that Comet PanSTARRS has faded (literally) into the background, many are asking what of Comet ISON that has been predicted to become one of the brightest comets in recent decades? At its brightest the comet may rival Venus in apparent magnitude, but this will last for a day or so at most and during this period the comet will be a difficult object from the northern hemisphere. However, there are a number of interesting positional features respecting ISON that commence in early September and which could form an interesting object for study in the early morning skies. This has to do with the appearance of both ISON and Mars over a period of some two months when the two objects will appear to keep close company as they pass from constellation Cancer into Leo. On October 15, ISON, Mars and Regulus (alpha Leonis) will appear together in a field of a little under 2˚. The comet may well have reached magnitude 9 by this date. Full details and maps will be given in October 2013. 2013 June 03 Dia. 1: Conjunction of 2013 October 15 as it may be seen at o3h 30m UT. (Left click to enlarge.) *Regulus, regulus and Erithacus rubecula Early autumn, very little wind (From Ruckblick II, JCV 2007) http://www.spanglefish.com/vetterlein/index.asp?pageid=273934

Comet. C/2011 L4 ( PanSTARRS ) 2013 April 02: A temporary PanSTARRS page has been opened. Important: The comet passes within less than 2 arc-degrees of the Great Andromeda Galaxy M31 April 2/3. Do not confuse one with the other! There is a location diagram on the SKY VIEW page showing the path of the comet up to April 19 2013. Update March 31. Comet PanSTARRS preparing to “bypass” the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) top left. 2013 March 31, 20h 37m UT. A 20 sec. exposure: Nikkor 135mm f/2.8 D300 ISO 800. (Left click to enlarge.) Comet in twilight: Comet C/2011 L4 (PanSTARRS ) imaged 2013 March 31, 20h 50m. A 20 sec. exposure Nikkor 500mm f/4, D300 ISO 800. Compare with image below noting improved colour correction for stars using this high quality lens. (Left click to enlarge.) A number of high quality images were obtained with lenses ranging from 135mm f/2.8 to 600mm f/4. A selection will be featured on site shortly. Update March 30. Extensive observations were made from 20h 15m to 21h 30m Comet C/2011 L4 ( PanSTARRS ) imaged 2013 March 30, 20h 50m UT. 150mm f/5 achromatic refractor: exp. 45 sec. D300 ISO 800. The star to the left of the comet is TYC 2270-570-1 mag. 6.74. Stars to magnitude 13 are visible. (Field: 75' x 55' approx.) Left click to enlarge. Update March 29. The comet is now circumpolar from the latitude of Orkney. This image was secured at 21h 04m UT between short breaks in cloud and before moonrise. A 4 sec. static camera, exposure; Nikkor 105mm f/1.8 D300: ISO 800. (The comet is presently out of reach from the observing station.) The star to the left of the comet is pi And. (mag. 4.33). The brightest star in the field (far left) is beta And. (mag. 2.07). Stars to magnitude 11.5 are visible in the frame. The fan-like tail is a little under 2 arc-degrees in this image. Estimated integrated magnitude of comet is 4.0 and a little brighter than predicted. (Left click to enlarge.) 2013 March 29, 21h 12m UT. A 4 sec. static camera, exposure; Nikkor 180 mm f/2.8 D300: ISO 800. (Left click to enlarge.) The appearance of the comet on March 29 was impressive in binoculars (7x50s) but far less so to the unaided eye, naturally. Update March 27. We have yet to observe the comet from Rousay. Observers elsewhere in the UK have been facing similar problems with weather and so forth. I have to reiterate my view that this comet was unlikely to be a spectacular event from the northern hemisphere. Unfortunately, the national and international media go hold of it and in their “ignorance” (word used politely but advisedly) raised expectations unnecessarily . Hopefully, with the Moon soon leaving the scene and with the comet’s increased declination, we should be able to achieve some images within the next week. BUT, we are now approaching the period of long twilight hours in the north and this, coupled with the appalling weather, would substantiate the view that one has to be something of a fanatic to do this job! UPDATE march 15: All attempts to observe the comet from Rousay have so far been foiled by cloud. As remarked previously, the comet is not an easy object from the northern hemisphere and reports from observer in this neck of the woods have been sketchy to say the least. We had the following from Telescope House earlier today: Comet Panstarrs is now visible from the UK and the entire Northern Hemisphere. It's still a fairly challenging object in the early evening (or morning) twilight because of its relative position to the Sun, but is putting on a fine show for those with a good westerly horizon. Telescope House Sales Manager, Peter Gallon, witnessed the Comet on the evening of Thursday 14th March at about 6.45PM and gave the following report: "Comet Panstarrs had a bright nucleus, which I'd estimate to have been mag +0. It would definitely be a really easy object if it were a bit higher in the sky. The tail was reasonably prominent - I'd estimate it to be about a degree in length. A really nice comet!"

UPDATE March 11. We have the following communication from the British Astronomical Association's Comet Section: Comet C/2011 L4 (PanSTARRS) is now setting after the Sun as seen from UK latitudes. It has put on a good show in the southern hemisphere and,although its brightness has been difficult to estimate in a bright sky, it may have reached zero magnitude. It certainly has a nice tail as can be seen in this image taken from Perth, Australia: http://www.dpreview.com/galleries/6455983989/photos/2452791/comet-panstarrs This comet is not well placed for northern observers. Maximum brilliance will occur around March 09 – 11, 2013 when the integrated magnitude may be in the order of 0.8 to 0.6. (We have yet to receive reliable estimates of magnitude from southern observers.) From about 11 March the comet will start to fade, halving in apparent brightness approximately every five days. It will likely drop below naked eye visibility within the first week of April.

Comet C2012 K5 (LINEAR) The first clear night (dusk to dawn) for over six weeks and the first “usable” night in 2013. As a result we have missed the best of this comet, which is heading south at a prodigious rate.

C2012 K5 (LINEAR) Imaged 2013 January 16, 19h 43m UT. 132mm f/7 apochromatic refractor, D300 SLR, a 50 sec. exposure at ISO800. Brightest star in field (dia. 50 arc-min) is TYC 4727-2098-1 mag. 5.86. Stars to magnitude 15 are visible despite Moon (phase 29%) separation 65°, altitude 22° 39'. The comet was at altitude 29° 44'. (Left click to enlarge.) A 50 sec. exposure 150mm aperture f/5 achromatic refractor ISO1200. (Left click to enlarge.) FEATURE - COMETS Introduction In astronomy one can divide subjects between the predictable and the un-predictable. For example, tables are issued many years in advance giving the positions for planets and other objects in the Solar System to a high degree of precision. (Unlike planets, comets with, few exceptions, move in highly elliptical and sometimes highly inclined – to the ecliptic – orbits*.) Also within the category of the predictable events are eclipses of the Sun and Moon, the occultation of stars by the Moon and other bodies in the Solar system. Amongst non-predictable events we have the appearance of the aurora, sunspots, visitations by comets hitherto unknown, the flare-up of stars – novae and super nova – transient phenomena on other planets and so on. Moreover, in the case of comets, although we may calculate their position as they approach the inner Solar System with some order of accuracy, their physical appearance is impossible to predict. Even our assumptions as to their orbits (or pathways) can sometimes come adrift, as was dramatically demonstrated in 2006 when Comet 73P/Schwassmann–Wachmann broke up into several fragments. Two of the larger portions were indeed recorded by us on Rousay (see fig. 6).

Fig. 1 Comet Hale-bopp 1997 March 28.842: Takumar135mm focal length f/3.5. MJH West Bergholt (film). Exposure: 10 minutes.

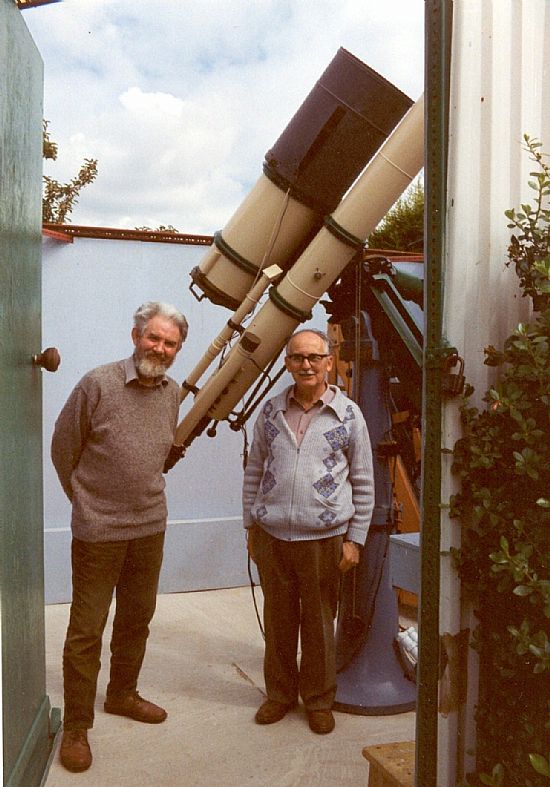

Fig. 2 Comet Hale-bopp 1997 April 04.864: 150mm aperture f/4.5 Cooke triplet MJH West Bergholt (film B&W). Exposure: 20 minutes. It would be difficult for me to position in order of priority and achievement my many and varied interests in the field of astronomy. Fortunately, I learned the hard way. That is to say, with little financial backing (few of us knew much in the way of luxury in the immediate post-WW2 period) I quickly learned economy of effort. Professionally my work in theoretical physics, celestial mechanics and binary stars in particular, was sufficiently academic for me to turn down an invitation from my old friend Patrick Moore (long before he had become an celebrity, of course) to appear on one of the early Sky at Night programmes. At various stages of my career has Patrick tempted me with exposure to the wider media all of which, for some strange reason, I have not followed up! But I digress. When I first joined the British Astronomical Association (BAA) as a schoolboy in 1951, I offered my services to the Computing Section. I quickly became involved in the calculation of cometary ephemeredes and the reduction of meteor observations, two related topics in many respects. (Remember in those days there were no electronic computers; all calculations involved many hours fingering through large tomes of mathematical tables to six figures of decimals or more; tedious to some but a worthwhile challenge to others, including myself.) A few years later I commenced, still as an amateur, the serious observation of comets and this activity has followed me through life to the present day. (As the composer Edward Elgar once said, the finest professionals are amateurs.) Some of my closest friends and associates have been, and are still, comet people. This included three BAA Comet Section Directors one of whom is Michael J Hendrie (retired) now in his early eighties but still very active as an observer. (fig.8) In addition to his tireless efforts for the Comet Section, Michael was also for over twenty years The Times Astronomy Correspondent. To Michael I am indebted for the fine images of Comet Hale Bopp (figs 1 & 2). (I should also wish to pay tribute to another good friend and colleague, Michael P Candy, formerly of the RGO, Sussex, and later active in Australia where he died in his prime, sadly.) Going back some fifty years I would have to give a very different picture for the comet observer compared to today. To record on film some of the fainter comets would require patient manual guiding at the eye-end of the telescope, sometimes spanning two or three hours. Our equipment comprised two Aldis 4 inch aperture f/4.5 cameras attached to the 5.2 inch Cooke refractor. The total weight of this outfit would have been in the region of 150 kilos, excluding the iron column upon which the massive equatorial head was bolted. Such things were only possible with the protection of an observatory (in this case 11ft diameter), revolvable dome. Contrast the above to our current range of equipment, most of which is portable, albeit at some expenditure of effort. For example, the fast 400mm f/2.8 Nikkor lens coupled to a D300 SLR is useful for a wide range of comets offering 2.3˚ x 3.4˚ field. This may be attached to an EQ6 equatorial mount offering adequate stability and may be set up within two to three minutes. The even faster 200mm f/2 lens is ideal for comets with tails up to 6˚ long. We have been fortunate in acquiring these fine S/H lenses at a fraction of their original cost since most photographic professionals these days upgrade to the latest automatic versions. Most of our recent comet work has been done with these lenses (fig. 4, also see Comet Garradd page).

Fig. 3 Comet Ikeya-Zhang; Date 2002 March 21. JCV (film), 400mm f/5.6 lens using Fujicolour 400 ASA, Pentax Super “A” SLR attached to the tube of a Meade 178mm Maksutov (cradle, fork mounting); exposure 4.5, minutes manual guiding; The length of the comet's tail is 4.5 arc degrees. Site: Braes, Sourin Valley, Rousay, Orkney. Note: there was a 7-day-old Moon contributing to sky glow.) Digital techniques have revolutionised astro-photography in all areas not least where comets are concerned when images that would have taken hours to secure on film may now be secured in a few minutes. With the advantage of repeated imaging, where time and conditions permit, the so-called stacking of images using specialist software can reveal detail that would have been unimaginable fifty years back.

Fig. 4 Comet Hartley 2010 October 15 at 22h 03m UT. a 50 sec. exposure 400mm f/2.8. D300 SLR, ISO1200.

Fig 5 Comet Swan 2006 September 30 at 20h 22m UT. Nikkor 105mm f/1.8 D100 SLR. (Looking NW from Springfield, Rousay, with house chimney stack to left.) However, there are drawbacks to the modern era mainly in the form of pollution from artificial light sources and aircraft condensation trails, Today it is impossible to image most regions of the night sky without encountering trails from artificial Earth satellites. There are literally thousands of bits and pieces up there constituting an inner cosmic dustbin that in the opinion of some is unjustified and irresponsible. For example, commercial space enterprises including a plethora of communications satellites for civilian and military use. The so-called sat-nav systems are superfluous to a good navigator, and I rather resent having our sky images disfigured by streaks of light in order to enable folk to chat by mobile phone from one end of a bus to the other! Fig. 6 73PSchwassmann-Wachmann 3. 2006 April 27. Nikkor 105mm f/1.8 D100 SLR. A composite image pair showing the two major fragmented portions of the comet: Note: the trail of an artificial Earth satellite passing through the coma of the “fragment” (right). Left click to enlarge. Number of personally observed comets. My personal tally of observed comets is in excess of fifty, or a little under one for every year since I commenced serious observational work on these objects in 1957. Most of these have been faint objects well below naked eye visibility, but a few have ranked amongst the finest ever to grace our skies of the many-recorded comets spanning hundreds of years. In fact, that very next year, in 1957, we were blessed with the very fine C/1956 R1 (Arend-Roland). My log for 1957 April 24 reads verbatim: Observed first with the naked eye the comet Arend-Roland from London at 20h 15m GMT. (37 Lloyd Baker Street, WC1, from where the comet lay almost over St. Pancras Railway Station.) A tail of about 3˚ long was easily seen. With 2 inch binoculars (7x50 Bar & Stroud) the tail was evidently longer but diffuse beyond 4˚ due to heavy artificial illumination of the sky. Three days later, observing from Brentwood, Essex, in a darker sky, I estimated the magnitude of the coma at 2.0 and the tail 6˚ in length. Movement against the stellar background was evident to the unaided eye over a period of an hour or so. A notable feature of Arend-Roland was its continually changing appearance. For many days it developed a down-pointing spike, which resulted from debris in its wake. I am sometimes asked to name the most impressive comet I have ever observed. One has to qualify their choice carefully. There have been some brilliant comets that have put on a grand display over a short period of a few days; recently comets C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) and McNaught 2007 (C/2006 P1) for example. Others have hung around for several weeks dominating that portion of the sky such as Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1; but the one I would give full-marks to would be Comet C/1996 B2 (Hyakutake). From the JBAA 1998.108..157: “Unfortunately it was almost totally overcast in the UK at the time of closest approach. One of the few observers to see the comet from Britain was Vetterlein in Orkney. He had clear skies on the early morning of March 25 (1996) and reported a 35˚ tail visible to the naked eye.” Unfortunately, my own image was on film and does not do justice to the comet. The comet’s coma (or “head”) passed almost through the zenith with the tail stretching away towards the southern horizon. Watching this spectacle alone in the early hours of a clear, late-March morning before twilight, gave me an understanding for how comets earned the reputation as portenders of catastrophe. Of course there have been a number of much brighter comets such as the famous Halley’s Comet in 1910 (the 1986 apparition was by no means favourable for Earth dwellers). C/1969 Y1 (Bennett), and Comet West in 1976. (I would recommend readers go to the Google image pages for illustrations of these comets.) As readers will have gathered, comets are very individual “creatures” in appearance, few if any replicate each other nor do those that return (and most do at some time or another) necessarily repeat their previous performances. One possible exception is Comet 17P/Holmes discovered in 1892 and extensively observed from Rousay 2007/8. (fig. 7a and 7b). Looking like a snowball with no perceptible tail, the comet’s appearance in this latest apparition resembled closely descriptions of its showing in the year of its discovery.

Fig. 7a Comet Holmes 2007 November 20 at 05h 33m UT. Tokina 300mm f/2.8 D100 SLR. A 50 sec. exposure at ISO 600. The bright star is Mirfak (alpha Persei mag. 1.82)

Fig. 7b Comet Holmes showing apparent size compared to the Moon (superimposed top left) 2007 November 26 at 17h 27m UT. Looking to the future we have the prospect of a brilliant “sun-grazer” comet when in November 2013 Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) approaches perihelion; some are even predicting that for a few hours the comet may be visible with the unaided eye in broad daylight. Unfortunately for we northern observers those in the southern hemisphere should have the best opportunity of seeing this one!

Fig. 8 Michael J Hendrie (right - closest to telescope) and John C Vetterlein at Michael’s Observatory, West Bergholt, Essex: 1993 August 25. All imkages JCV excepting figs. 1 & 2 (MJH) & 8 (Pat Hendrie). * See Basics page: “Orbits etc.” coming soon.

|    |

|

| ||