INVERNESS & BLACK ISLE U3A

STUDY DAY

Landscape, Industry and Energy

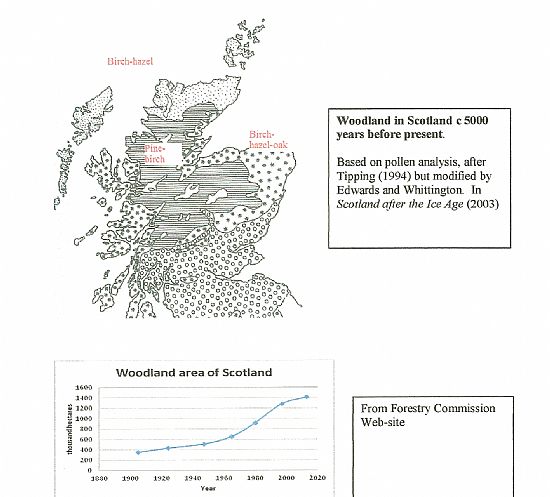

Five thousand years ago, most of Scotland including the islands was tree-covered below the 600 metre contour (map overleaf). Caithness, west Sutherland and the islands were dominated by birch and hazel with pine and birch predominant further south and some oak down the west coast and along the Moray Firth. Woodland covered most of the areas now covered in blanket peat. Beginning in the stone age, agriculture has contributed to removing the tree cover, not just by felling but by inhibiting regeneration through grazing animals and man-made fires as a tool for grazing-management. By the end of the first world war, woodland area in Scotland was reduced to about 4% of the land area. Two hundred and fifty years ago, “improved” agriculture began to impose straight-line field boundaries in the straths and coastal planes and depopulated the uplands. Grazing continues to inhibit tree regeneration.

Especially during the seventeenth century, pre-industrial iron smelting destroyed large areas of woodland. However, the Highlands largely escaped the industrial revolution except for coastal industries associated with fishing and support for the Royal Navy. North Sea oil and gas exploration and extraction had a more recent impact on the coasts.

Plantation forestry has a very different visual impact from natural woodland. Most of it dates from since the first world war (see graph overleaf) and woodland now covers 18% of Scottish land area of which about 14% is planted. About half of the Scottish area lies north of the highland line especially around the east coast firths and their feeder valleys, in the Great Glen and in Argyll and Bute. Although initially based on native pine, it has increasingly depended on monocultures of exotic species. Because of poor timber quality and the disappearance of some anticipated markets, such as pit-props and paper-making, the huge investment of the last century has not and will probably never be recovered. Plantation forestry was initially imposed with little thought for landscape impact but this has improved. Natural regeneration of native species is now being encouraged but still requires unsightly deer fencing.

Large hydro-power schemes were initially developed for aluminium smelting (Foyers 1896, Kinlochleven 1904 and Fort William 1929) and their above-ground pipelines are still visually intrusive. The general-purpose hydro-power developments completed from 1950 to 1965 (see overleaf) were justified against opposition (particularly from the fishing lobby) as providing employment, rural electrification and profits for the development of the Highlands. The visual impact was reduced by creating tunnels rather than surface pipelines and stone-cladding the power stations. The associated pylons are unsympathetic but the cost of underground transmission lines was and remains high. The dams have largely “blended in” and the reservoirs (mostly enlarged natural lochs) can be considered a positive landscape feature, though less so when low water levels expose unsightly margins. There is technical scope for more hydro-power development.

Because they are most efficient when sited on the ridges, windfarms can have a major visual impact. They can be largely hidden from the valleys and major tourist roads but are very visible from the high ridges and tops. However, not everybody considers them unsightly. There is scope for further development so long as the price premium for “renewable” energy is maintained. The disadvantage of fluctuating output can be offset by combining wind-farm and hydro-power including pumped schemes.

Completion dates of principal hydroelectric dams (Scheme in brackets):

1950 Loch Sloy (phase 1)

1951 Clunie (Tummel-Garry)

1952 Loch Mullardoch (Affric-Cannich)

1957 Loch Fannich, Glascarnoch, Vaich (Conon valley)

Loch Quoich, Loch Loyne, Cluanie (Moriston-Garry)

1959 Allt-na-Larigie, Lochan Shira Mor (Loch Sloy, phase 2)

1960 Loch Shin

1961 Lochan na Lairige, Loch Breachlaich, Loch Lyon, Loch Giorra (Breadalbane)

1963 Loch Monar, Loch Beannacran (Strathfarrar-Kilmorack)

1965 Ben Cruachan, Loch Nant (Awe pump storage)

1975 Loch Mhor (Foyers)

from The Dam Builders.

Summary of Discussion Group on Industry and Energy

There was general agreement that agriculture had been a formative influence on the Highland Landscape and continues to be so. Most members considered that major developments such as new estate roads and large buildings should require planning permission.

Plantation forestry is seen as visually intrusive but more recent efforts to soften forest boundaries and vary the species mix were acknowledged. We welcomed the encouragement of natural regeneration and non-geometric planting of indigenous species, even when this requires unsightly deer fencing. However, more coherent policies for the control of deer and destocking of sheep were considered a better solution.

Members were worried by the apparent ad-hoc nature of electricity generation projects across the Highlands and felt the need for a coherent strategy which would take account of the visual impact of generating equipment and structures for power transmission. In particular, there was some scepticism that the Scottish Government would meet its renewable energy targets, despite the proliferation of windfarms. There was some support for returning to power generation close to the point of use although it was pointed out that this would be highly problematic for the major conurbations. Another view was to develop solar power from distant deserts. Small-scale hydro and river-flow systems were generally supported.

Neil Fisher