INVERNESS & BLACK ISLE U3A

STUDY DAY

Landscape

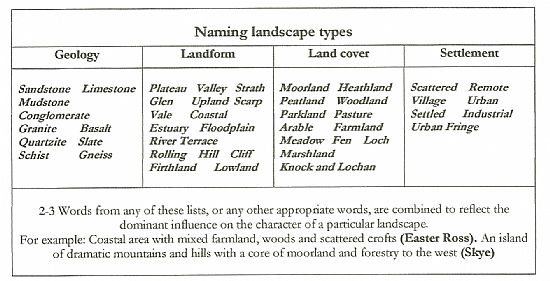

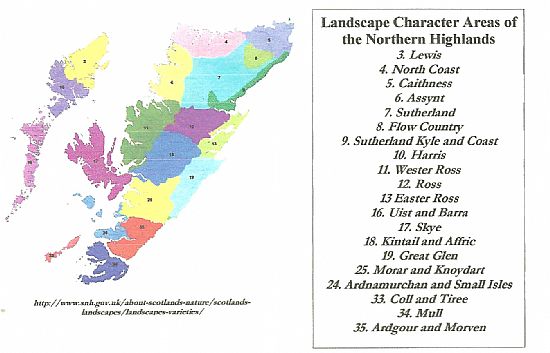

In Scotland 79 broad Character Areas have been mapped and described nationally. They describe landscape, wildlife, natural and cultural features and the differences in landscape character across the country. Local studies have assessed their landscapes in finer detail and the information is used to inform the planning and management of change across the countryside.

Landscape character is ‘a distinct, recognisable and consistent pattern of elements in the landscape that makes one place different from another, rather than better or worse’. Put simply, it is what makes an area unique.

Particular combinations of geology, landform, soils, vegetation, land use, field patterns and human settlement create character. In turn, character makes each part of the landscape distinct and gives each its particular ‘sense of place’.

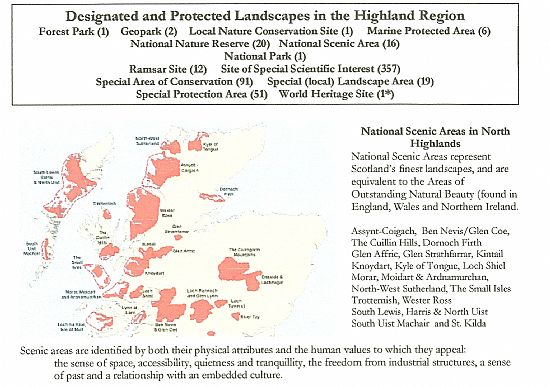

Designated and Protected Landscapes

Protected areas may be designated to meet the needs of international directives and treaties, national legislation and policies or more local needs and interests.

Highland Council Planning Policy 61, Landscape

New developments should be designed to reflect the landscape characteristics and special qualities identified in the Landscape Character Assessment of the area in which they are proposed. This will include consideration of the appropriate scale, form, pattern and construction materials, as well as the potential cumulative effect of developments where this may be an issue. The Council would wish to encourage those undertaking development to include measures to enhance the landscape characteristics of the area.

Highland Biodiversity Action Plan

In Highland, a number of key habitats often support significant numbers of priority species. Continuing to manage these habitats well will usually maintain the associated species. Highland is particularly important for:

- native pine woodlands (particularly important for wood ants, fungi, red squirrel, capercaillie and other priority species)

- blanket bog (the peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland are the largest area of blanket bog in the world)

- montane habitats (not identified as a national priority habitat in their own right, despite supporting many priority species)

- arable farmland (8 priority bird species are associated)

- marine and intertidal habitats (the Moray Firth is the most important in Scotland for its wintering waterbirds, supporting on average 142,000 birds) and rivers, lochs and their associated habitats.

The development of the rural landscape is increasingly planned through the application of agricultural and forestry grant schemes and environmental regulation.

O Gjolberg (1995)

Summary of Discussion Group on Landscape

16 people were involved in the Landscape Discussion Group, defining what they understand a Highland Landscape to be and the ways in which development impacts on these landscapes and how these effects could be mitigated.

Members of the Group were asked to describe a landscape that they considered epitomises the best of the Highlands and its characteristics. The landscapes chosen ranged across the Northern Highlands from Tongue and Caithness in the north to Torridon in the south and from Skye in the west to Findhorn in the east. Surprisingly, perhaps, no one elected to choose landscapes in the ‘honey pots’ of Knoydart and Kintail, Lochaber or the Islands

In terms of landscape elements everyone described the physical landform associated with their chosen area and without exception, it was the juxtaposition of land, sky and water that was valued. Given that much of the morning had been given over to describing how landscape is, for the most part, the product of man’s activities it is interesting to note that only four members of the group identified human activities within their chosen locality.

The entire group, however, attributed human values to their landscape. The most popular were those of isolation and peace/quiet, closely followed by the sense of space and distance, wildness, beauty and accessibility and remoteness.

Asked to describe landscapes that they would avoid, without exception. they all chose areas where active change and development impinged on the human values outlined above.

The townscapes of Inverness and Invergordon, particularly their approaches, were heavily criticised as being cluttered and without character. The new Culloden Centre and the site of the Battlefield was also singled out as being out of scale and character, losing much of the ‘atmosphere’ that people had associated with the site in the past.

Block forestry, Fish Farms and Wind Farms were also seen as being obtrusive. It was suggested that the scale and size of such features were at odds with the natural landscape, as were their rigid, linear shapes … at variance with the ‘flow of the land’. Concern was expressed at the way in which Wind Farms (and pylons), telecommunication masts and block forestry dominate the skyline. Interestingly hydro dams, although obvious intrusions into the landscape, were not criticised in the same way and several members of the Group thought they actually made a valuable contribution to the character of the landscape. No one was quite sure whether this seeming contradiction was due to the fact that dams and hydro lochs have merged into the landscape over time and people had got used to them, that they do not impinge on the skyline, or whether the presence of water ‘softened’ the impact of these structures.

In terms of protecting the landscape there was a general consensus that change is inevitable but that certain areas (‘wild areas’) should be protected from all development that would detract from the human values of peace/quite, tranquillity and the sense of space and distance that had figured so highly in the group’s definition of the Highland Landscape. It was also strongly felt that such protection should cover agricultural and estate activities, including the building of hill tracks.

It was also felt that that while most of the landscapes we had identified were large blocks of land there is also a need to encourage local communities in the creation and protection of small scale, local landscape features. This is seen of particular value in Easter Ross and along the coast of the Moray Firth.

In conclusion two questions were drawn up for the consideration of the Panel:

- How do we give ordinary people a stake in the Highland Landscape and its development?

- Are we devoting enough resources to recording what is going on around us so that we make meaningful decisions about the future of the landscape?

David Rendell