Northern Ireland

In 1963, the prime minister of Northern Ireland, Viscount Brookeborough, stepped down after 20 years in office.

His extraordinarily long tenure was a product of the Ulster Unionist domination of politics in the north since partition in 1921.

By contrast, the Catholic minority had been politically marginalised. This was largely a product of Northern Ireland's two-thirds Protestant majority, but was exacerbated by the drawing of local government electoral boundaries to favour unionist candidates, even in predominantly Catholic areas like Derry.

Additionally, the right to vote in local government elections was restricted to ratepayers - again favouring Protestants - with those holding or renting properties in more than one ward receiving more than one vote, up to a maximum of six.

This bias was preserved by unequal allocation of council houses to Protestant families. Catholic areas also received less government investment than their Protestant neighbours.

Police harassment, exclusion from public service appointments and other forms of discrimination were factors of daily life, and the refusal of Catholic political representatives in parliament to recognise partition only increased the community's sense of alienation.

But there had been improvements. Post-war Britain's new Labour government had introduced the Welfare State to the north, and it was implemented with few, if any, concessions to old sectarian divisions.

As a result, Catholic children in the 1950s could reap the benefits of further and higher education for the first time. It would, in time, expose them to a world of new ideas and create a generation unwilling to tolerate the status quo.

But for now, anti-partition forces had been neutralised and the unionists were firmly in control. There was little indication in 1963 of the turmoil that was about to engulf Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland had been left relatively prosperous by World War Two. War production had favoured its heavy industries, with the boom continuing into the 1950s. But by the 1960s, as elsewhere in Britain, these were in decline.

It was as a result of Viscount Brookeborough’s failure to address the worsening economic malaise that he had been forced out in 1963 by members of his own party.

He was replaced by a former army officer, Terence O'Neill, who immediately introduced a variety of bold measures to improve the economy.

But O'Neill realised that for his programme of modernisation to succeed, he would also have to address Northern Ireland's simmering social and political issues.

In a series of radical moves, he met with the Republic of Ireland's prime minister Sean Lemass - the first such meeting between Irish heads of government for 40 years - and put out feelers to the nationalist community in the north.

This represented a serious threat to many unionists, since the Republic's constitution still laid claim to the whole island of Ireland. O'Neill's policies provoked outspoken attacks from within unionism, not least from the Reverend Ian Paisley who rose to prominence at this time.

With Catholic hopes raised on one side and unionist fears on the other, the situation quickly threatened to boil over. Violence finally erupted in 1966 following the twin 50th anniversaries of the Battle of the Somme and the Easter Rising - touchstones for Protestant and Catholic communities respectively.

Rioting and disorder was followed in May and June by the murders of two Catholics and a Protestant by a 'loyalist' terror group called the Ulster Volunteer Force.

O'Neill immediately banned the UVF, but it was too late. The cycle of sectarian bloodletting that would become known as 'the Troubles' had already claimed its first victims.

Despite O'Neill's initiatives, many Catholics were impatient with the pace of reform and remained unconvinced of the prime minister's sincerity. The result was the founding of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (Nicra) in 1967.

Nicra did not challenge partition - probably in an attempt to draw as much cross-community support as possible - although the membership remained predominantly Catholic. Instead, it called for the end to seven 'injustices', ranging from council house allocations to the 'weighted' voting system.

Initially peaceful civil rights marches descended into violence in October 1968 when marchers in Derry defied the Royal Ulster Constabulary and were dispersed with heavy-handed tactics.

The British government summoned O'Neill to London to explain the situation. Pressure was brought to bear, and shortly afterwards a package of reforms was announced by the Northern Ireland government, including the fairer allocation of council houses and an ombudsman for complaints.

But the reforms failed to deliver fully on Nicra's programme, including one-man-one-vote and the repeal of the repressive Special Powers Act.

After a brief cessation, the civil rights marches continued, organised at first by a group called People's Democracy and later by Nicra. Once again, the RUC response was heavy-handed and would only serve to inflame the Catholic community further.

Increasingly embattled by dissent in the UUP, O'Neill gambled everything on a general election - which he dubbed the 'crossroads election' - to try and win a mandate for change from the public.

The gamble failed amid poor electoral support and desertions from O'Neill's camp. Nonetheless, he hung on grimly for another two months before resigning in April 1969.

Against a backdrop of rising violence, O'Neill's replacement, James Chichester-Clark, opted to continue with his predecessor's reforms.

Paramilitary groups had now begun to operate on both sides of the sectarian divide, while civil rights marches became increasingly prone to confrontation.

More problematic still, the Orange Order's marching season had begun. Following the annual Apprentice Boys' march in August 1969, civil unrest in Belfast became a three-day explosion of nationalist rioting in Derry.

The so-called 'Battle of Bogside' only ended with the arrival of a small body of British troops at the request of Chichester Clark - a significant acknowledgement that the government of Northern Ireland was fast losing its grip on security.

A political response came in the shape of the joint 'Downing Street Declaration' by Chichester-Clark and the British prime minister Harold Wilson. Once again, the British government had intervened to force the pace of reform.

The declaration sought to placate both communities by stating its support for equality and freedom from discrimination, while reasserting that Northern Ireland would remain part of the UK as long as that was the will of the majority of its people.

A blizzard of reforms then followed, including the setting up of a variety of bodies to allocate council housing, investigate the recent cycle of violence and review policing. The latter recommended the disbanding of the hated 'B Specials' auxiliaries, the disarming of the police and the setting up of the Ulster Defence Regiment under the control of the British Army.

Outraged loyalists responded with yet more civil unrest and violence. Attacks on Catholic areas escalated, and many homes were burned.

The IRA - one of whose stated aims was the defence of the Catholic minority - had remained largely inactive during this period. It had abandoned its last campaign of violence in 1962, having been successfully contained by internment and other counter-measures.

In late 1969, the more militant 'Provisional' IRA (PIRA) broke away from the 'Official' IRA. Like the Official IRA, the PIRA supported civil rights, the defence of the Catholic community and the unification of Ireland. But in contrast it was prepared to pursue unification in defiance of Britain and would use violence to achieve its aims.

At the same time, loyalist paramilitaries were also organising. The UVF was joined by the Ulster Defence Association, created in 1971, which rapidly expanded to a membership of tens of thousands, but somehow avoided being banned.

In the middle was the British Army. Its various attempts to control the PIRA, such as house-to-house searches and the imposition of a limited curfew, only served to drive more recruits into the ranks of the paramilitaries.

In March 1971, Chichester-Clark resigned and was replaced by Brian Faulkner. Unrest in the province had achieved a new level, prompting the new prime minister to reintroduce internment - detention of suspects without trial - on 9 August 1971.

It was a disaster, both in its failure to capture any significant members of the PIRA and in its focus on nationalist - rather than loyalist - suspects.

The reaction was predictable, even if the ferocity and extent of the violence wasn't. Deaths in the final months of 1971 exceeded 150. It was sadly still far from the bloodiest year of the Troubles.

Policing the province was fast becoming an impossible task, and as a result the British Army had adopted increasingly aggressive policies on the ground.

Then on 30 January 1972, the army deployed the Parachute Regiment to suppress rioting at a civil rights march in Derry. Thirteen demonstrators were shot and killed by troops, with another dying later of wounds.

The events surrounding 'Bloody Sunday' remain the subject of intense controversy. But as a result of the killings, new recruits swelled the ranks of the IRA and yet more British troops were deployed to the province to try and contain the ever-rising tide of violence.

Protestants also expressed their growing discontent with the formation of the Ulster Vanguard, an umbrella organisation for loyalist groups that was able to attract tens of thousands to public meetings.

The British government, led by Prime Minister Edward Heath, decided to act, removing control of security from the government of Northern Ireland and appointing a secretary of state for the province.

The Stormont government resigned en masse in protest at this perceived assault on their powers. Heath responded by immediately introducing what would become known as 'direct rule' - government of Northern Ireland from Westminster.

Amid outpourings of unionist anger following the end of government at Stormont (its last meeting was on 28 March 1972) the province descended into an abyss of sectarian bloodshed that would claim 496 lives by the end of 1972 - the highest annual death toll of the Troubles.

One of the worst crimes in a year full of atrocities was 'Bloody Friday' - the simultaneous detonation of more than 20 PIRA bombs in Belfast - which claimed nine lives.

By March 1973, a new political initiative was being tabled by the British government. It outlined plans for a new Northern Ireland assembly, elected by proportional representation, and a government for the region in which Protestants and Catholics would share power

It also proposed the creation of a 'council of Ireland' that would give the Republic a role in Northern Ireland's affairs - directly confronting one of the unionists' greatest fears.

Remarkably, the new assembly elections in June 1973 produced a majority of pro-power sharing representatives, but they were set against a large minority of implacably anti-power sharing unionists.

Nonetheless, the 11 ministry power-sharing executive started work in January 1974. Of its many inherent weaknesses, perhaps the greatest was the exclusion of anti-power sharing representatives from the executive and from the negotiations for the Council of Ireland.

The Sunningdale Agreement (named after the town in Berkshire where the negotiations took place) had agreed a 14-member Council of Ireland. It terms were vague, but the agreement raised the possibility that the Republic could one day gain some decision-making powers in Northern Ireland.

Unionists were split by the agreement, and the forthcoming British general election of February 1974 gave the anti-Sunningdale bloc an ideal opportunity to derail the process.

Representing the election as a referendum on Sunningdale, anti-agreement unionist candidates won 11 of Northern Ireland's 12 parliamentary seats. It was a disaster for the pro-Sunningdale assembly, since it could no longer claim to represent public opinion.

Nonetheless, the British government refused to call new assembly elections, and on 14 May 1974, the assembly, perhaps rashly, restated its support for Sunningdale. As a result, the Ulster Workers' Council - a coalition of Protestant trade unionists - called a general strike in the province later that same day.

Then on 17 May, loyalist bombs exploded in Dublin and Monaghan, ultimately claiming the lives of 32 people in the worst single outrage of the Troubles.

Within two weeks the shutdown had become total, with roadblocks, power-outages and a near-complete cessation of industry. The British government, now led by Harold Wilson, seemed unwilling to engage in this new and potentially crippling confrontation.

Indeed, Wilson's accusation that the strikers were 'sponging off Westminster' only helped galvanise support for the UWC.

On 28 May, the pro-Sunningdale unionist members of the power-sharing executive took the matter out of Wilson's hands. They resigned and direct rule was immediately reintroduced. It would last for another 25 years.

Over the next decade, a variety of peace initiatives were suggested, tested and ultimately defeated.

New security policies were also introduced. These included increasing the size of the RUC and UDR while shrinking the army presence, thereby placing the emphasis on the people of Northern Ireland policing themselves.

In 1976, the British government also removed the 'special category' status of paramilitary prisoners. Since 1972, paramilitary prisoners had held some of the rights of prisoners of war. Now classified as ordinary criminals, they were to be confined in the new Maze Prison near Belfast, in its distinctively-shaped 'H-Blocks'.

Viewing themselves as freedom fighters rather than criminals, PIRA prisoners embarked on a series of protests, including refusing to wear prison-issue clothing during the so-called 'blanket protest'. This was followed in 1978 by prisoners smearing their cell walls with excrement as a 'dirty protest' against having to 'slop out'.

The protest escalated to a hunger strike in 1980, which was called off when the prisoners mistakenly believed they had been granted concessions.

A second hunger strike began in 1981, led by Bobby Sands. During his strike, he was put forward for the vacant Westminster seat of Fermanagh - South Tyrone - and won.

It was a clear demonstration of the level of popular support for the strikers, but the British government led by Margaret Thatcher refused to make any concessions. Sands died on 5 May 1981. Another nine prisoners would die before the strike was called off in October.

As a result of the strikes, a new strain of bitterness had entered the turmoil of Northern Ireland politics. But at the same time, Sands' by-election victory had shown the potential power of political engagement.

In late 1981, Sinn Fein, the IRA's political wing, formally adopted a policy of contesting elections while also supporting the continued use of violence to achieve its ends.

Sinn Fein won the by-election following Sands' death, and in June 1983, Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams defeated Gerry Fitt, former leader of the centre-ground nationalist SDLP (and now an Independent Socialist) to win the Westminster seat for West Belfast.

These electoral successes raised the very real possibility that Sinn Fein could replace the more moderate SDLP as the political voice of the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland.

Relations between the Republic of Ireland and Britain had reached a new low during the hunger strikes.

And Republic-backed proposals for the future of Northern Ireland had also received a sharp rebuff by Thatcher, who was not in conciliatory mood having narrowly escaped an IRA bomb attack at the Conservative party conference in Brighton in October 1984.

Nonetheless, the rising political effectiveness of Sinn Fein and the danger of interminable violence if the issue of Northern Ireland remained unresolved led Thatcher and her Irish counterpart Garret FitzGerald to reach an agreement.

The Anglo-Irish Agreement, signed in November 1985, confirmed that Northern Ireland would remain independent of the Republic as long as that was the will of the majority in the north.

But it also gave the Republic a say in the running of the province for the first time, with the setting up of the Intergovernmental Conference to discuss security and political issues.

The agreement also stated that power could not be devolved back to Northern Ireland unless it enshrined the principle of power sharing.

Reaction was diverse. Sinn Fein and the Republic's opposition party Fianna Fail condemned the agreement for acknowledging that Britain had a legitimate role in Northern Ireland.

Centre-ground nationalists like the SDLP welcomed what they saw as a new and constructive development.

Unionist opinion was uniformly horrified, believing that the first steps had been taken towards abandoning the province to a united Ireland. Huge demonstrations, strikes and marches were held, and all 15 unionist Westminster MPs resigned their seats.

The resulting by-elections actually saw Sinn Fein and Ulster Unionist support fall, with the latter losing a seat to the SDLP. If the intention of the agreement had been to lessen the polarisation of Northern Ireland politics and bolster the constitutional and non-violent SDLP, these were tentative indications that it might be working.

By 1987, unionists had tacitly conceded that their campaign to derail the agreement had failed, and once again began to cooperate with government ministers.

The violence of Northern Ireland's paramilitary groups still had more than a decade to run and the sectarian divide remained as wide as it had ever been.

In 1990, things began to change for the good. External factors came to bear. A sympathetic British government, US interest, and EU membership brought economic renewal. The Catholic Churches' influence was waning in the Republic, which was also booming economically. All of these influences made a big contribution to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

In 1991 and 1992, thanks to John Hume's Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP), most political groups met with British Prime Minister John Major. The 1993, Downing Street Declaration was the outcome, stating that Britain had no, 'selfish, strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland'. In other words, what the people of Northern Ireland vote for, they will get.

Sinn Fein's leader, Gerry Adams, then announced an IRA ceasefire. British troops reduced their presence, and the streets began to seem normal. In 1995, the British and Irish governments drew up 'Framework Documents' outlining a self-governing body, and for relations between that body, Westminster and Dublin. The Framework documents were for discussion only. The main controversy in discussions on the documents was the issue of 'decommissioning'. The IRA refused to decommission while British troops remained in Northern Ireland. This was unacceptable to the British or Ulster Unionists who have an understandable mistrust of the IRA. The talks broke down. On February 9, 1996, the cease-fire ended with the IRA's destruction of Canary Wharf in London.

In May 1997, Tony Blair's Labour Party won a landslide victory in Britain and brought a renewed commitment to Northern Ireland. Fianna Fail's Bertie Ahern was an equally good-willed leader of the Irish Republic. Northern Ireland Secretary Mo Mowlam allowed Sinn Fein into all party talks in Stormont, after a new cease-fire was acknowledged. The decommissioning issue was being dealt with simultaneously with the Stormont talks as suggested by peace broker Senator George Mitchell.

On April 10, 1998, after intense negotiations, the historic Good Friday Agreement was signed and greeted enthusiastically by those waiting for the breakthrough at home. The agreement ultimately allowed Northern Ireland's fate to be decided electorally within its own borders, and also set up good relations with the Republic and allowed religious equality in Northern Ireland. It was resoundingly endorsed.

The new Northern Ireland assembly had legislative and executive control over most areas of life, whilst independent commissions were set up to examine policing and other issues. Assembly elections put the Ulster Unionists (UUP) in charge with the SDLP in second, closely followed by Ian Paisley's Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Gerry Adams' Sinn Fein. David Trimble became Northern Ireland's First Minister in the new assembly, with SDLP's Seamus Mallon as his deputy.

Peace is not a foregone conclusion. The Orange Order marches remain a very contentious issue. The IRA have splintered again, and internal Republican violence remains contentious. The newly formed Republican dissidents, the Real IRA devastated the town of Omagh, killing 29 people. Condemnation was swift from all sides including Sinn Fein. Cease-fires were called by the extreme Real IRA, INLA and LVF (Loyalist Volunteer Force), but not universally upheld. The decommissioning issue continues to dog the Assembly. Chris Patten's independent policing commission was controversial. It advocated radical changes to the RUC who since 1922 had been almost 100% Protestant. The commission wanted the force to be 30% Catholic. He wanted it renamed, with new uniforms, and to stop flying the British flag. The lack of willing to carry out the commission's suggestions was to become for Republicans what decommissioning was to Unionists.

In October 1999, Mo Mowlam, seen as something of a hero for her efforts, was replaced by Tony Blair's close political ally, 'spin doctor' Peter Mandelson. The treatment of Mowlam is highly political and remains controversial.

Gang war between rival factions of Loyalist Paramilitaries broke out. IRA gangs continued to live beyond the law. In January 2001, Mandelson was replaced by John Reid, and things continued as usual. Relative peace remained but little political progress was being made.

In the general election of 2001, the UUP clung on to power, but recent elections have changed the political landscape. Ian Paisley's DUP topped the most recent poll, with Gerry Adams' Sinn Fein the biggest Nationalist party. With political extremism at the fore in Northern Irish politics, it is difficult to predict Stormont's future. Paisley is a fierce opponent of the 'Good Friday Agreement', and refuses to share power with Sinn Fein. Perhaps, he just wants to direct the future, a position he has never been in before. Many people see him simply as a hate-filled, anti-papist madman. Being physically removed from the UN buildings for verbally abusing the Pope during an address lends credence to this opinion. However, in day to day runnings, both Catholics and Protestants view him as a fair local politician. No doubt, there is truth in both sides of the argument.

Inclusive talks continue, and the Irish watch, weary but hoping that something can be achieved. Many have seen it all before. So many hopes have been smashed that many view the situation as hopeless. However, a younger, outward looking generation is growing up, and the longer the peace, the more likely a constructive generation will emerge.

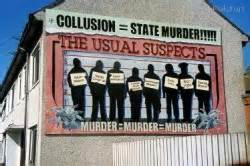

British State Collusion with Loyalist Death Squads in Northern Ireland

On 8th July 1981, on the Falls Road in Belfast, Nora McCabe stepped out of her house in her bedroom slippers to go to the shop. Almost immediately, she was shot dead by a plastic bullet, fired from a passing police jeep. At her inquest, one after another, the five police involved repeated the same story that there was a riot taking place and they had acted in self-defence. It looked like the inquest was going their way until suddenly the McCabe family’s lawyer, a young Pat Finucane, introduced a new witness – a Canadian cameraman who happened to be in the area at the time. The film was shown to the court, and revealed that the Falls Road that morning was deserted. It shows the jeep coming down the road, turning into Linden Street where Nora lived and it shows the puff of smoke from the gun that fired the lethal shot. There had been no riot, and Nora had been killed in cold blood.

If the rule of law had prevailed in Belfast at the time, one might expect a prosecution of the killers to have emerged, and for the officers to have been tried for perjury. Instead, the inquest was stopped, never to be reopened; the young solicitor’s assassination was arranged by a British agent; and the man in charge of the police in the landrover, Jimmy Crutchley, was given a medal and a promotion. “This is what happens”, Robert McClenaghan explains, “to the bad apples.”

Cases such as these are the tip of the iceberg. McClenaghan estimates that around 1100 people have been killed by loyalists as a result of collusion with the agencies of the British state. “In our opinion we could put what the British state has been doing for twenty or thirty years on a par with what happened in Chile or what happened in Argentina. It may not have been on the same numerical scale, but the policies were the same.”

Eight years ago, Robert and hundreds of other relatives of those murdered joined forces to create An Fhirinne, a united campaign to discover the truth about how and why their loved ones were killed; to discover, as they put it, “not just who pulled the trigger, but who pulled the strings”. An Fhirinne, which is Gaelic for “the truth”, now represents over 250 families. Their struggle has not been easy: “At the start we were dismissed as republican propaganda: the attitude was ‘how dare you try to assert that the British government could be involved in murdering its own citizens?’ But bits and pieces of evidence, circumstantial or otherwise, began to come out and it got to the point where the British couldn’t hold it back anymore.”

The result was the Stevens inquiry. After eleven years of investigations, Sir John Stevens, former head of the Metropolitan Police and “hardly a republican sympathiser”, concluded that collusion had indeed taken place. “From about a million pages of evidence” explains Robert, “he was only allowed to publish twenty. But those twenty were damning”. Stevens concluded that he had amassed enough evidence to mount 25 prosecutions – including against senior RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary – the police), special branch and British military intelligence personnel. He handed this evidence to the DPP (Director of Public Prosecutions). Years passed, until finally, in 2007 – four years after being handed the files – the DPP announced that there would be no prosecutions. The state institutions would protect their own, no matter how great the evidence of their crimes. As Robert put it; “this was the British state covering up the mass murder of its own citizens”.

State cover up of murder is something of which Robert has personal experience. On December 4th 1971, McGurks Bar was blown up by a UVF bomb, causing the biggest single loss of life of the ‘Troubles’ until the Omagh bombing. His grandfather was amongst the fifteen killed. At the time, he says: “we hadn’t a clue about media, about press statements or anything else, we just knew our grandfather was dead. He was blown up, at 75 years of age, and within hours he was being called a bomber in the media. The British army, the RUC, the unionist politicians were all issuing the statement that this was an IRA bomb which my grandfather and the others had been making when it exploded prematurely. You’ve no idea the impact it had on my grandmother or my father. It’s hard enough to deal with a death, especially a brutal death like murder. But then on top of that to be told lies by the police…”. Six years later, whilst being interrogated over an unrelated murder, a UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force) member named Robert Campbell admitted to being the getaway driver for the bombing that day. Campbell had already been named as the culprit, along with four others, in an anonymous tip-off the previous year. “Now if you were in special branch, and you had a list of five and one of them confesses, you would think at the very least, you should go out and arrest the other four. You don’t have to watch CSI to work this out.” Even then, the official line continued, and although Robert Campbell was sent to prison, none of the others were even arrested.

In the early 1970s, this type of collusion – the institutions of state covering up loyalist killings – was the norm. What we now know is that both the RUC (the police) and the UDR (the army) were also arming the loyalist militias and providing them with intelligence: “This isn’t us whose saying this, this is a British government report that was unearthed in the public records at Kew. One document, declassified under the 30 year rule, shows that between 5 and 15% of the UDR were also members of the death squads of the UDA or the UVF, and that the biggest single source of weapons for the UDA and the UVF was the UDR.”

What Stevens’ inquiries had unearthed, however, was that by the mid-80s collusion had shifted from this type of informal (albeit widespread) collaboration amongst people on the ground to a crucial plank of British state policy. Loyalist death squads had effectively become integrated into the British chain of command.

Finding the fingerprints of Brian Nelson, a leading member of loyalist militia the UDA, on British army documents, Stevens’ team had Nelson arrested. During his time in prison, Nelson admitted he was a British agent, and that far from being placed in the UDA to disrupt its operations, he was in fact there to facilitate them. Nelson, it emerged, had been given access to army intelligence files to improve the UDA’s targeting and assassinations, and had been aided by MI5 in facilitating the import of a huge arms shipment in from apartheid South Africa in 1987. This haul, which included rocket launchers, fragmentation grenades, Browning pistols and over 200 AK47s, more than tripled the loyalists’ killing rate, from 71 over the six years prior to the shipment’s arrival, to 229 during the six years afterwards.

However, the idea that Nelson and his handlers were simply ‘bad apples’, out of the control of the higher military and political authorities, says Robert, is demolished by what happened after Nelson was arrested: “Two weeks away from his trial, there was an extraordinary, unbelievable meeting that took place here in Belfast. At the meeting was the British Prime Minister, John Major; the head of all the six county judges, Brian Hutton; Basil Kelly, who was due to be the trial judge; the Attorney General, Sir Patrick Mayhew who later became Secretary of State for Northern Ireland; the head of the DPP at the time, and the head of the RUC. They didn’t want Nelson to get into the dock and blow their cover about how all these murder gangs had been allowed to proceed. So they came up with a plea bargain that was put to Nelson: If he would plead guilty to lesser charges, they’d ensure he didn’t spend too long in prison”. The multiple murder charges against him were dropped, and instead he was given a ten year sentence for conspiracy in a court case that lasted less than a day. He served less than half this sentence, and was announced dead the day the Stevens Inquiry report was published. Robert finds this hard to believe: “My gut instinct is that he is in South Africa, or a British dependency where he feels safe and secure and he’s just got away with it. He might be dead and I might be wrong, but it was just too coincidental that on the exact same day as Stevens published his report that implicated him, this 4 line statement got released saying that he’s dead.”

Nelson’s handler was a man named Gordon Kerr, of the Forces Research Unit, established under Thatcher essentially to professionalise collusion. His subsequent career demolishes the ‘bad apple’ theory even further: “He actually left the north under the cloud of being a mass murderer and involved in all these killings – but then went on to become British military attaché in China! Stevens put in a request to interview Kerr, and was told he had moved from China and was now on operational duties. He was actually based in Basra, in Iraq. Do you understand the significance? See all the covert killings that were going on in Iraq? There was an incident in Basra where two British operatives were dressed up in Arab dress at a checkpoint, and the local police tried to stop them but they killed them. Then they were arrested and brought into the police station but a British tank came in and smashed down the walls to take them away. That was Kerr’s unit. So this is not only Belfast or the six counties that we’re talking about, this is transporting terror around the world and this is where they perfected their techniques.”

More evidence was unearthed by the 2007 report of the police ombudsman, Nuala O’Loan, into the killing of a young Protestant, Raymond MacCord jnr, by the UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force): “This case blew the lid off everything. She found that there was a UVF gang headed up by Mark Haddock which was responsible for almost 20 murders and he had his own special branch handlers who were using him and letting him do this. The first person he killed was a woman, a Catholic woman called Sharon McKenna. These people were being paid from the public purse – an allowance every week by their special branch handlers. And after he killed Sharon McKenna, he got an increase in the amount of money his handlers were paying him.” Shortly after releasing her report, O’Loan was replaced by a new ombudsman, Al Hutchinson – “in my opinion he is seen by the British government as a safe pair of hands, whose not going to rock the boat. He’s not measured up at all.” Last month, Hutchinson published a report exonerating the police involved in the McGurks case. “That was a brutal report. A loyalist bomb and for forty years they blamed the IRA, and they said that was a proper investigation. It’s another whitewash in our opinion; they didn’t even get the names right on the list of people killed.”

Nevertheless, the evidence of collusion continues to mount, and the British government has adopted ever more contorted positions to avoid it coming out. A number of key cases, including Finucane’s and that of another solicitor Rosemary Nelson, were raised by Sinn Fein as part of the political negotiations with the British government at the Weston Park talks in 2001. The British appointed Canadian former High Court judge Peter Cory to look into six specific cases (including two of alleged Irish state collusion with the IRA). As Robert puts it, “they thought he was going to come over and be a safe pair of hands; another Widgery”. But it was not to be. In 2003, he reported that there was enough evidence of collusion for separate inquiries to go ahead. “So the British government was in a dilemma. They weren’t expecting Cory to recommend inquiries in these six cases and they were now looking at the possibility of a Pat Finucane Inquiry running for months. Senior British army, police and politicians, including members of Maggie Thatcher’s cabinet could have been subpoenaed. So they were faced with a dilemma and what they did was change the law.” Until then, the relevant law was the 1921 Public Inquiries Act, which specified that any public inquiry would have an independent chairperson, who could pick their own panel, and all hearings would be held in public. Blair was to change all that: “They rushed through parliament a new inquiries act in 2005 which says that it is a British government minister who will now decide who the chairperson of any future inquiry is, a British government minister who will decide what evidence can be heard in public and what in private, as well as which witnesses. And when the inquiry’s finished hearing and comes to its conclusions, the same British government minister will now decide how much evidence will be given to the public and how much has to be redacted and held back for 30 years. So the government are now offering Pat Fincane’s family this truncated, almost impossible idea of an inquiry.” The family have, unsurprisingly, rejected this, fearing a whitewash.

That collusion was taking place, however, has never been doubted by republican communities, as it was manifestly obvious in their daily lives, as Robert explains: “It was common knowledge at the time. We had 30,000 British troops on our streets. Now, the British army’s just fought a war in Iraq and the highest they ever had there was 8000. So this was probably one of the highest militarised parts of the world. They might not have had 30,000 by the 1980s but don’t forget there were 11,000 RUC and 2 or 3000 UDR and the police reserve, all acting as back up to the British army, so it was a massively militarised society, covered with checkpoints and helicopters. And then they would suddenly disappear, and the area would be deadly silent; and every one of us used to say, ‘someone’s going to get killed tonight’. Because you knew once the checkpoints had disappeared, this was the death squads getting the green light to come in.”

Robert is like a walking encyclopaedia on these issues. The dates, the names, the places, roll off his tongue with ease. In the two and a half hours I spent with him, there is the basis for a book, never mind an article. Neither is what he is telling me hidden knowledge – it is public and openly available. And the enormity of it is staggering: “the biggest modern story of the British state” as he puts it: the state running death squads against its own citizens; and the personnel involved now doing the same thing around the rest of the world. And yet, “this story has never impacted in Britain. It’s amazing to me, we’re so close, we speak the same language, we travel back and forth…but there’s a glass wall there that we haven’t been able to penetrate.”

But then, the media’s servility towards British policy in Ireland is nothing new. Robert believes they too need to be brought to book: “You kill the people first of all, you shoot them dead and then you issue a statement saying he was a gunman or she was a nail-bomber. The BBC then reports the statement and the media just rolls out the story and blackens their names. So that’s the first thing that an Irish person reads the next morning in the Sun or the Daily Mail – it didn’t matter if it was a redtop or a broadsheet, Telegraph, Express, Guardian, Observer – by and large they all towed the line.”

“The idea of collusion is like a spider’s web. At one end you have the assassins who are provided with weapons, provided with information, and are then allowed to come into an area which has been full of military and is then cleared. The military are brought back to barracks, the death squad comes in, sledgehammers the door down, has a map of the house, goes up and does the killing and drives away. The police then arrive, and there is no proper investigation: no ballistics, no forensics – and no adequate prosecutions. In the case of John Stevens, he had twenty five files on some of the most senior police and army which he gives to the DPP on a plate. And they sat on it from 2003-2007. So that implicates then the DPP’s office, which implicates the whole of the legal and judicial system, not to mention the media. So if we are talking about collusion, we try to paint this picture of a spider’s web. Everybody, whether it’s MI5, RUC, special branch, police military intelligence, the civil servants, the media, the courts, the prosecution service, they’ve all at one point or another failed to do what they’re supposed to do.”

The answer? “We want some sort of independent international inquiry that’s independent of the British and Irish governments but will have the authority to subpoena witnesses. Not just republican, but loyalist or British cases as well. The British government try to portray this image to the world that they were peacekeepers trying to keep two warring factions apart, to stop the Catholics killing the Protestants and the Protestants killing the Catholics; instead of saying this was our colony and we were actively involved as combatants and participants on one side, namely the pro-British loyalist side. And what that meant in reality is that they armed the loyalists, they gave them information and then they let them loose on our community over a generational period and killed upwards of 1000 people. So they can’t then be the people that sit in judgement. We don’t want British judges coming over and bringing republicans and loyalists in, and saying ‘tut tut that shouldn’t have happened, now do you want to tell your story?’ And then the British state gets off scot-free.”