Genocide In Cambodia

The Cambodian Genocide refers to the attempt of Khmer Rouge party leader “Pol Pot” to nationalize and centralize the peasant farming society of Cambodia virtually overnight, in accordance with the Chinese Communist agricultural model. This resulted in the gradual devastation of over 25% of the country’s population in just three short years.

Cambodia, a country in Southeast Asia, is less than half the size of California, with its present day capital in Phnom Penh. In 1953 Cambodia gained its independence from France, after nearly 100 years of colonialist rule. As the Vietnam War progressed, Cambodia’s elected Prime Minister Norodom Sihanouk adopted an official policy of neutrality. Sihanouk was ousted in 1970 by a military coup led by his own Cambodian General Lon Nol, a testament to the turbulent political climate of Southeast Asia during this time. In the years preceding the genocide, the population of Cambodia was just over 7 million, almost all of whom were Buddhists. The country borders Thailand to its west and northwest, Laos to its northeast, and Vietnam to its east and southeast. The south and southwest borders of Cambodia are coastal shorelines on the Gulf of Thailand.

The actions of the Khmer Rouge government which actually constitute “genocide” began shortly after their seizure of power from the government of Lon Nol in 1975, and lasted until the Khmer Rouge was overthrown by the Vietnamese in 1978. The genocide itself emanated from a harsh climate of political and social turmoil. This atmosphere of communal unrest in Cambodia arose during the French decolonization of Southeast Asia in the early 1950s, and continued to devastate the region until the late 1980s.

The Khmer Rouge guerrilla movement, founded in 1960, was considerably undermanned in its early days. The movement’s leader, Pol Pot, was educated in France and was an admirer of “Mao” (Chinese) communism – Pol Pot envisioned the creation of a “new” Cambodia based on the Maoist-Communist model. The aim of the Khmer Rouge was to deconstruct Cambodia back a primitive “Year Zero,” wherein all citizens would participate in rural work projects, and any Western innovations would be removed. Pol Pot brought in Chinese training tactics and Viet Cong support for his troops, and was soon successful in producing a formidable military force. In 1970, the Khmer Rouge went to civil war with the U.S. backed “Khmer Republic,” under lieutenant-general Lon Nol. Lon Nol’s government had assumed a pro-Western, anti-Communist stance, and demanded the withdrawal of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces from Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge guerillas were finally successful in deposing Lon Nol’s government in 1975. Under Pol Pot’s leadership, and within days of overthrowing the government, the Khmer Rouge embarked on an organized mission: they ruthlessly imposed an extremist program to reconstruct Cambodia on the communist model of Mao’s China. It was these extremist policies which led to the Cambodian genocide.

In order to achieve the “ideal” communist model, the Khmer Rouge believed that all Cambodians must be made to work as laborer in one huge federation of collective farms; anyone in opposition to this system must be eliminated. This list of “potential opposition” included, but was not limited to, intellectuals, educated people, professionals, monks, religious enthusiasts, Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, and Cambodians with Chinese, Vietnamese or Thai ancestry. The Khmer Rouge also vigorously interrogated its own membership, and frequently executed members on suspicions of treachery or sabotage. Survival in Khmer Rouge Cambodia was determined by one’s ability to work. Therefore, Cambodia’s elderly, handicapped, ill, and children suffered enormous casualties for their inability to perform unceasing physical labor on a daily basis.

At the onset of the Cambodian civil war in 1970, the neighboring country of Vietnam was simultaneously engaged in a bitter civil war between the communist North Vietnamese, and the U.S. backed South Vietnamese. Under the Khmer Republic of Lon Nol, Cambodia became a battlefield of the Vietnam War; it harbored U.S. troops, airbases, barracks, and weapons caches. Prior to the Lon Nol government, Cambodia had maintained neutrality in the Vietnamese civil war, and had given equal support to both opposing sides. However, when the Lon Nol government took control of Cambodia, U.S. troops felt free to move into Cambodia to continue their struggle with the Viet Cong. As many as 750,000 Cambodians died over the years 1970-1974, from American B-52 bombers, using napalm and dart cluster-bombs to destroy suspected Viet Cong targets in Cambodia. The heavy American bombardment, and Lon Nol’s collaboration with America, drove new recruits to Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge guerilla movement. Many Cambodians had become disenchanted with western democracy due to the huge loss of Cambodian lives, resulting from the U.S.’s involving Cambodia in the war with Vietnam. Pol Pot’s communism brought with it images of new hope, promise, and national tranquility for Cambodia. By 1975, Pol Pot’s force had grown to over 700,000 men. Within days of the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in 1975, Pol Pot had put into motion his extremist policies of collectivization (the government confiscation and control of all properties) and communal labor.

Under threat of death, Cambodians nationwide were forced from their hometowns and villages. The ill, disabled, old and young who were incapable of making the journey to the collectivized farms and labor camps were killed on the spot. People who refused to leave were killed, along with any who appeared to be in opposition to the new regime. The people from entire cities were forcibly evacuated to the countryside. All political and civil rights of the citizen were abolished. Children were taken from their parents and placed in separate forced labor camps. Factories, schools, universities, hospitals, and all other private institutions were shut down; all their former owners and employees were murdered, along with their extended families. Religion was also banned: leading Buddhist monks and Christian missionaries were killed, and temples and churches were burned. While racist sentiments did exist within the Khmer Rouge, most of the killing was inspired by the extremist propaganda of a militant communist transformation. It was common for people to be shot for speaking a foreign language, wearing glasses, smiling, or crying. One Khmer slogan best illuminates Pol Pot’s ideology:

“To spare you is no profit, to destroy you is no loss.”

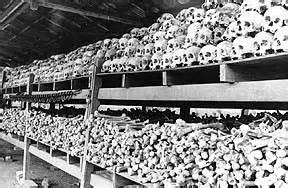

Cambodians who survived the purges and marches became unpaid laborers, working on minimum rations for endless hours. They were forced to live in public communes, similar to military barracks, with constant food shortages and diseases running rampant. Due to conditions of virtual slave labor, starvation, physical injury, and illness, many Cambodians became incapable of performing physical work and were killed off by the Khmer Rouge as expenses to the system. These conditions of genocide continued for three years until Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978 and ousted the Khmer Rouge government. To this point, civilian deaths totaled well over 2 million.

Cambodia lay in ruins under the newly-established Vietnamese regime. The economy failed under Pol Pot, and all professionals, engineers, technicians and planners who could potentially reorganize Cambodia had been killed in the genocide. Since Cambodia had now fallen under Vietnamese (Communist) control, foreign relief aid from any western, democratic state was unlikely. Throughout the 1980s, the U.S. and U.K. instead offered financial and military support to the Khmer Rouge forces in exile, who had now sworn opposition to Vietnam and communism. The Vietnamese occupation and the continual threat of Khmer Rouge guerilla forces preserved Cambodia in underdeveloped and prehistoric conditions- until Vietnam’s eventual withdrawal in 1989. In the following military conflicts of 1978-1989, an additional 14,000 Cambodian civilians perished. In 1991, a peace agreement was finally reached, and Buddhism was reinstated as the official state religion. The nation’s first true democratic elections were held in 1993.

On July 25, 1983, the “Research Committee on Pol Pot’s Genocidal Regime” issued its final report, including detailed province-by-province data. Among other things, their data showed that 3,314,768 people lost their lives in the “Pol Pot time.” Beginning in 1995, mass graves were uncovered throughout Cambodia. Bringing the perpetrators to justice, however, has proved to be a difficult task. The UN called for a Khmer Rouge Tribunal in 1994; the trials finally began in November of 2007, and are expected to continue through 2010. Many suspected perpetrators were killed in the military struggle with Vietnam or eliminated as internal threats to the Khmer Rouge itself. In 1997, Pol Pot himself was arrested by Khmer Rouge members; a “mock” trial was staged and Pol Pot was found guilty. He died of natural causes in 1998. The last members of the Khmer Rouge were officially disbanded in 1999. Currently, the state of affairs in Cambodia is relatively tranquil. Today, Cambodia’s main industries are fabrics and tourism; foreign visitors to Cambodia surpassed 1.7 million in 2006. However, the BBC reports that corruption remains a serious issue in Cambodian politics. International aid from the U.S. and other countries is often embezzled by bureaucrats into their private accounts. This illegal seizure of foreign aid has greatly added to the widespread income disparity which affects most Cambodian citizens today.