ÆLFRIC of EYNSHAM

Aelfric of Egoneshám

Aelfric, Abbot of Eynsham, a prolific writer and scholar, made an incomparable contribution to the corpus of Old English literature in England. His unflagging efforts to regulate and improve the knowledge of leading churchmen contributed to his eponymous titles of Aelfric the Grammarian, Aelfric the Homilist and Aelfric of Cerne (Cernel). Aelfric's own writings show that he was desirous of being an effective instrument of preaching and catechesis.

Aelfric of Eynsham's devoted, conscientious scholarship, learned status and much-esteemed legacy led, perhaps inevitably, to his mistaken identification with the distinguished personage of Aelfric of Abingdon who went on to become Archbishop of Canterbury. In fact, Aelfric of Eynsham did not seem to have risen beyong the modest role of Abbot.

There are few certain dates for the life of Aelfric of Eynsham although the usual dates tend to span the years c. A.D. 955 - c. A.D. 1010 (some sources prefer later dates, whilst other sources confuse and conflate 'Aelfric of Eynsham' with other clerics named 'Aelfric'). His early education certainly took place at the old monastery in Winchester under the guidance of Aethelwold, the Benedictine Bishop of Winchester [AD 963-984]

In order to appreciate the zeal which fuelled Aelfric’s subsequent literary output and forged his scholarly reputation, it would not be mis-placed to acknowledge his debt to Bishop, later Saint, Aethelwold. Aethelwold not only placed a high value on learning and the arts but was also a notable, if extremist, presence in the monastic reform movement who did not flinch from his endeavour to raise monastic standards where they had fallen into laxity.

In AD 987 when Aelfric was in priest’s orders, he was requested by ealdorman Aethelmaer of the Abbey at Cerne Abbas in Dorset to undertake the teaching of its Benedictine monks. Both Aethelmaer and his father Aethelweard were enlightened patrons of learning. The honour extended to this young priest indicates that Aelfric was a man of learning, a man of principle and a man of ideas. In a letter to Wulfsige, Aelfric emphasised what needed to be taught to priests and what was required of the masspriest :

'...tell the people on Sundays and festivals the meaning of the gospel [in English] and about the paternoster and about the creed also, as often as he can, as an incitement to men that they may know the faith and observe Christianity..."

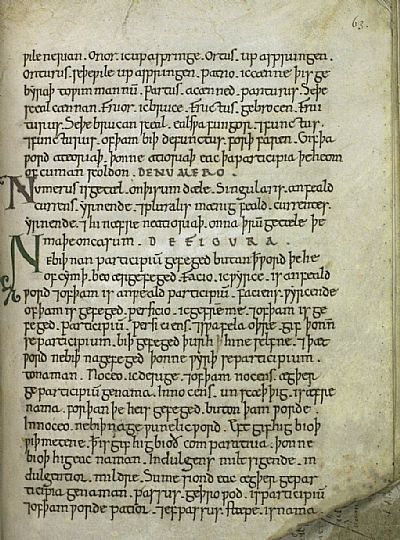

Cerne Abbey

It was at Cerne Abbey that Aelfric planned the first two of his authoritative homilies. He was concerned that his fellow Englishmen had little opportunity to access the Scriptures, either in Latin or in their own language of West Saxish, a dialect of Old English. This he attempted to rectify by producing what is considered to be the first Grammar in medieval Europe to translate Latin into vernacular Old English; the first topical Glossary and the first Colloquy which was written as an aid to learning conversational Latin.

Around AD 996-997, Aelfric went on to write a third series of homilies, this time on the Lives of the Saints. His writing was produced during a period of embattled, continued reform not only against the prevailing tide of Celtic Christianity but also against the heathen beliefs of Danish invaders lodged on British soil.

At the particular request of Aethelwold, Aelfric was invited to translate Holy Scripture in the form of the Book of Genesis up to Abraham and Isaac into the vernacular, that being the West Saxish dialect. This dialect of Old English was the language of the West Saxons [Westseaxe] and probably the East Saxons [Eastseaxe] and the South Saxons [Suthseaxe] as spoken in southern England by those who had arrived from Germania.

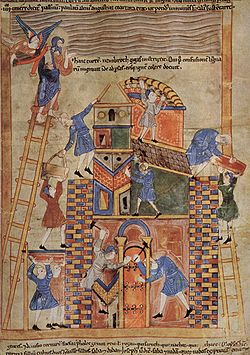

Tower of Babel from an illustrated m.s. of Aelfric's preface to the Book of Genesis [British Library]

This difficult translation represented a revolutionary point in time. Aelfric recorded his misgivings about undertaking the momentous labour of translating such sacred texts into the vernacular: "the aforesaid book is in many places so densely written and so profound in its spiritual sense". He realised the enterprise would have proceeded with or without his involvement and although it was customary to cling to existing syntax and vocabulary in translation, in order to produce the very best translation he had to take the revolutionary decision to render the language as it was disposed to him.

Aelfric's achievement was to overcome the twin perils of obscure content and unyielding language of the Old Testament; time and again Aelfric was compelled to overcome the limitations of the West Saxish language to express deeply obscure and abstract concepts. He triumphed. His imaginative translation made the old scriptures sing their meaning through the metrical medium of poetic alliteration; he delighted the senses with his deep love of the Mystical.

The next certain date recorded in Aelfric’s life is AD 1005 when he moved to Eynsham near Oxford to take up the post of first Abbot at the new monastery commissioned by his patron and friend, Aethelmaer. Although the monastery was new, the minster of Eynsham was well established. Aelfric remained at Eynsham for the rest of his life.

At Eynsham he continued his prodigious endeavour of research and writings. He was known to have corresponded with Wulfstan, the thunderously impassioned Archbishop of York. Their intriguingly contradictory styles, methods and beliefs are worthy of closer scrutiny.

Aelfric’s natural humility was not at odds with his decidely forward-thinking opinions for the time in which he lived and even extended to a personal appeal for his several works in the West Saxish language to be protected from exposure to future scribal error or interpolation as evidenced by his instructions to pay every attention to preserving his careful and judiciously-chosen words.

Until the end of his days Aelfric remained not just a trusted and highly respected representative of the Anglo-Saxon church but his master’s true pupil. He adopted and cherished Bishop Aethelwold’s principled stance on the importance of purity and 'claennes', of being well schooled and a merciful, effective messenger to the faithful, always teaching by authoritative word and good example.

How long his reforms lasted in the wake of the Norman Conquest is debatable. What is certain is that there was an almost immediate weakening of Old English as the medium of written communication and with it the vital lifeline to and between clergy and parishioners. The champion of vernacular West Saxish language may not have had the capacity to transcend the outfall of the linguistic watershed of Norman French but his fine texts and translations were invested with a vitality that reaches us still, many centuries after they were written.

Thanks are due to the insight and industry of the Aelfric Society and to subsequent scholars for restoring Aelfric’s works in translation and indeed to modern technology for making these works available in digitised formats.

"Blind is the teacher if he has no book-learning and thus deceives the laymen with his lack of knowledge.'

[Aelfric of Eynsham]